Decline?

I’ll start with genes but then go wildly off-topic, or rather I’ll start off-topic and get to where I really want. Here is our updated paper on natural selection in the US. It’s now coauthored with Tobias Edwards, a PhD student at the University of Minnesota.1 I’ve written about the paper before: one new thing is that Tobias extended the results to cover three generations, looking at respondents’ number of siblings, i.e. their parents’ fertility, and their number of grandchildren.

This is nice because the US respondents, from the Health and Retirement Study, are quite old. So when we study their parents’ fertility, we are looking back early in the twentieth century, well before the development of the US “Great Society” welfare programs of the 1960s. The economic theory of fertility, which I and Abdel Abdellaoui applied to explain natural selection, isn’t about the welfare state — it’s just driven by participation in the modern economy. But the welfare state has always been a kind of stalking horse rival explanation. Crudely put, maybe if you can’t make a lot of money working, you have kids and go on benefits. Well, we can’t say much about the size of natural selection across different generations, but the pattern of natural selection remains the same: polygenic scores are selected against if they correlate positively with education, and selected for if they correlate negatively with it. So while this isn’t a knockdown proof, it is a piece of evidence that modern patterns of natural selection pre-date the welfare state.

Does it matter whether natural selection is a recent or a long-term phenomenon? On the one hand, if it’s long-run, it could be more serious. A shift that makes a population just a bit less healthy or smart in one generation could add up to a big shift over several generations.

On the other hand, a long-run problem seems less urgent. If a particular social policy was having effects on the gene pool, we might want to reevaluate that policy. But if the culprit is the whole history of modern economic growth, then first, there doesn’t seem to be a realistic policy fix; and second, you might argue that it isn’t a real problem. Ten generations ago people had higher polygenic scores! Yeah, but they also had rickets, while we have smartphones. We can relax about the genes, because the countervailing forces of economic progress are obviously much stronger. (The ultimate version of this argument is that if we get AGI, we can let computers do the thinking and stop worrying about human capabilities entirely.)

My view is that natural selection itself probably isn’t a big problem for humanity, but simultaneously it does index a big problem. So now let’s go off-topic.

Kinds of people

This is the more general problem: the kind of people that get us over the starting line of economic take-off are not the kind of people who result from economic take-off. Natural selection on DNA is an example of that, an interesting one because it’s empirically measurable. But it’s not a morally important example. If all that the modern economy did was affect DNA via natural selection, I wouldn’t care about it.2

It’s not morally important because ultimately, intelligence isn’t morally that interesting — at least, not the kind of intelligence measured by IQ tests, or which gets you a university degree and a well-paid job. I am not saying that IQ is socially unimportant. Lots of research says that IQ strongly correlates with many important individual outcomes, including your education and salary.

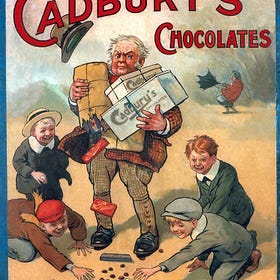

By analogy, imagine a caricature of Edwardian Britain, where people’s life outcomes were strongly determined by their accent. An Oxford accent would make you rich, a Jarrow accent condemns you to poverty. And suppose that the country’s accents were shifting towards Jarrow. Would this be a big concern? Of course not. Something can be very predictive of individual outcomes, without being important at the collective level. IQ isn’t quite like accent — society genuinely needs smart researchers and productive workers — but it is also not as important as the individual level correlations make it seem.

What is important, then?

I take the general problem seriously, which puts me at loggerheads with most economists, and indeed most serious thinking people. (By the way, Noah Smith has a great writeup of the issues I’m going to talk about, from the opposite side, but with unusually thoughtful and engaged.)

The disagreement is that I genuinely think our civilization has declined. This point of view is mostly confined to those who meme, and post-liberals nostalgic for the Middle Ages. Serious people know the facts of history and economic growth. History shows that selfishness, greed and the other vices were not invented yesterday, and that what institutions — the Church, say — preach in any era does not always align with what they practice. Economic growth means that an ordinary person today is better off than a king in 1800. I accept these points. I also don’t buy environmental doom-mongers who think our society is on the path to human extinction. Yet I still think that civilization was higher and is now lower, so why?

Economic growth was not inevitable. Most of human history shows very little of it. It required difficult collective problems to be solved. They could only be solved by creating a very distinctive type of culture and in fact a distinctive type of person. The conditions for the “take-off” into economic growth were cultural, not just a matter of cheap coal or expensive workmen.

I think civilization has declined because I think that culture, and its associated personality type, were valuable in themselves. It is a kind of culture that never existed before and perhaps will never exist again. Uniquely extreme in its demands of people. Uniquely focused on creating the people that could meet those demands. I would even say that that predecessor civilization has not just declined, but ended, even though in a thousand ways we are still swimming among its wreckage.

I am talking loosely about one civilization, but it had many different levels and regions. Northern European Protestantism was built upon Western Christianity, and within that, Prussia and England are very different. And Meiji Japan is completely different from all of these. But here I am ignoring these differences to focus on what they had in common, which is the intensity of their culture. So I will keep talking about the “predecessor civilization” as if there were one of it.

Weak men create hard times?

This story is the first three panels of the Hard Times Create Strong Men meme, in which Hard Times Create Strong Men, Strong Men Create Easy Times and Easy Times Create Weak Men. Some versions of the story add the fourth panel, where Weak Men Create Hard Times. For example, Daniel Bell thought that capitalism relies on premodern cultural roots, which it chews up. Or you can tell a version in which the decadent West is overthrown by traditionalist Russians or tough Communists, who are prepared to spend money on guns rather than butter.

These are old arguments, with equally old counter-arguments. In The Fable of The Bees, Mandeville described how a modern economy, built on “vice”, provided the money for the sinews of war. Take that vice away and “So few in the vast hive remain, the hundredth part they can’t maintain against th’insults of numerous foes…”

Bare virtue can’t make nations live

in splendour; they, that would revive

a golden age, must be as free,

for acorns, as for honesty.

The 2023 version of this is:

In a way, Weak Men Create Hard Times is an optimistic story of continuous renewal. John Stuart Mill talked about this, though I don’t think he saw it as very likely:

A civilization that can thus succumb to its vanquished enemy, must first have become so degenerate, that neither its appointed priests and teachers, nor anybody else, has the capacity, or will take the trouble, to stand up for it. If this be so, the sooner such a civilization receives notice to quit, the better. It can only go on from bad to worse, until destroyed and regenerated (like the Western Empire) by energetic barbarians.

But there is not really much evidence for the WMCHT thesis. There are obvious ways in which history isn’t cyclical. Technological progress is cumulative: even the Dark Ages3 did not reverse all technological advances in Europe.

Are any “Weak Men” problems serious enough to do more? Robin Hanson suggests that fertility decline is caused by cultural drift, and he worries that this will lead to a drop in innovation. (So, Weak Men Create Less Men Create Hard Times.) That is a reasonable worry. It’s backed by the basic insight of modern economic growth theory, which is that ultimately growth is driven by ideas, and ideas come from people. So, more people → more ideas → faster growth, and conversely less people → less ideas → slower growth. But declining fertility is partly driven by people investing more in their children, which might make them smarter and more innovative. (Economists of the family talk about a “quantity-quality tradeoff”.) Maybe for some parameters a growth model will predict declining innovation and growth, or even absolute falls in GDP, due to lower population, but that sounds more like a speculation than a reliable prediction.

I don’t deny that declining population is a serious policy issue:

But I don’t think it is an inevitable catastrophe.

There are other ways in which culture might affect economic growth and lead to Hard Times. For example, if people are not enculturated to be trustworthy, then that might lower trust, which in turn could make the economy less efficient. But most of these ways seem more likely to marginally affect growth levels in certain places, rather than to cause the whole world or even a single region to decline.

Chess at the end of history

It seems just as likely that our technological progress has made the demanding culture of yesterday unnecessary. My favourite example is credit. In the 18th century, credit in the banker’s sense was interwoven with credit in the moral sense, of being an upstanding member of society who paid his bills. Extending credit was a matter of trust. Today, credit is something precisely measured by complex, specialized computer systems which care about your last telephone bill but not at all about your marriage vows. And it is embodied not in your social standing, but in a little plastic rectangle: 💳.

Similar things happened to employment. In the twentieth century, employers started to care less about hiring religiously motivated hard workers out of Sunday School. Instead, they hired the Time and Motion Man, who could measure how hard workers were performing and sack the shirkers. Today, Amazon has automated the whole process.

Cultural conservatives often say that if you lose internal constraints on behaviour, you will have to impose external ones. But it also works the other way round: when you have easier ways to check behaviour externally, you don’t need tight internal constraints.

Another way progress undermines demanding culture is simply by making us richer. One thing that wealth buys is not having to adjust to other people. You move into your own place and don’t have to share with flatmates. The same is true at the collective level. When people live on top of each other in tenements, they need to work hard at getting on with each other. When they have their own houses, they can do their own thing. The invention of the car let individuals choose where they could live, instead of needing to be near the train that brought them to their workplace, close to all their colleagues. Eventually even within families, each person can have their own bedroom, screen with preferred media, and mealtimes. No more fighting over when to sleep or what to eat or watch.

But this suggests a subtler dystopia than civilizational collapse. Maybe continued progress will rob us of aspects of our humanity. That could even be worse than a return to barbarism, and harder to escape from. Science fictions from The Machine Stops and Brave New World to The Matrix imagine humanity enslaved and vitiated by its own comfort, a kind of redundant appendix among the perfected machinery created to serve it.

Or there’s a gentler version of the same story: the humans at the End of History. Here there’s no barbarian invasion, and no enslavement by our machines. We live on, but in a slightly desultory way — what Noah Smith called “shallow”. We have no more mountains to climb (and maybe conquering space is too hard?) We play chess against machines that could beat a grandmaster. We go jogging….

Ways of being

Even this gentle, adagio version of history ending gives people like me a vague sense of unease. But exactly what gets lost in it? To cash that unease out requires taking a view on what matters about human cultures.

A sceptic could reply that the virtues of the predecessor civilization are simply becoming unnecessary. The point of courage, justice, wisdom and temperance is to get us to cooperate. Ultimately, they were ladders to today’s materially abundant societies. Now we’ve made the climb, we can discard them.

This view perhaps can’t be proved wrong, but it can be relativized. During most of the time in which progress has been a real observable thing, people have not seen it as simply material. Instead, they’ve counted two kinds of progress, material and moral. Macaulay wrote: “the history of our country… is eminently the history of physical, of moral, and of intellectual improvement,” and he devoted pages of his History of Britain to moral improvement specifically. Perhaps recent generations have been uniquely insightful in understanding that virtues are means, not ends in themselves. I think a more reasonable point of view is just that moral values are themselves products of different societies. Sure, we at the end of history uniquely valorize material progress, but that doesn’t mean we are right in any absolute sense. It’s just what happens at the end of history.

What is admirable about the predecessor civilization? A first shot might be, let’s call it the “Chartres cathedral” view:

Aber ein Turm war groß, nicht wahr? O Engel, er war es, —

groß, auch noch neben dir? Chartres war groß —, und Musik

reichte noch weiter hinan und überstieg uns.

But a tower was great, no? O angel, it was —

Even next to you? Chartres was great… and music

Reached still farther up and overtook us.

Rilke, Seventh Duino Elegy

Part of what makes medieval European architecture wonderful is that it seems to relate so intensely to belief. It’s hard to imagine modern architecture recapturing that, even though it must be technically far more advanced. On this view, what matters is the creations of culture: Chartres and the B Minor Mass.

In itself, that is superficial. It’s not the buildings per se but the mentality they reveal. You don’t have to be naïve about the past to think there is something interesting about Thomas More facing torture and replying “my masters, these are threats for children”. Or, for a funnier example, the hermit who lived in the hills above Rome with a tame bear who knew the hours for mass.4 Or for something less exotic, the culture of my mother’s generation. (The underlying similarity across time and place: a highly demanding set of internalized rules.)

Our precursor cultures were shaped by extreme pressure: the need to cooperate in a world without the modern institutions that make cooperation easy. What emerges under pressure can be valuable, as a fierce critic of Christianity had to admit:

The essential and invaluable element in every morality is that it is a protracted constraint: to understand Stoicism or Port-Royal or Puritanism one should recall the constraint under which every language has hitherto attained strength and freedom — the metrical constraint, the tyranny of rhyme and rhythm. How much trouble the poets and orators of every nation have given themselves! … But the strange fact is that all there is or has been on earth of freedom, subtlety, boldness, dance and masterly certainty, whether in thinking itself, or in ruling, or in speaking and persuasion, in the arts as in morals, has evolved only by virtue of the ‘tyranny of such arbitrary laws’….

Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

Can I do better than just saying “there is something interesting” about the predecessor civilization? It is hard to decide between ultimate values. But if one role of culture is to contribute to human survival, then there is an option value in having a diverse ecology of different cultures. In that sense the loss of a civilization is like the loss of a species. There are some related reflections here:

Ordinary human life

I woke up early and read a book. At 7 I turned on the radio. A bit later, I got up, fed and walked the dog, playing a game on my smartphone. I skinned a mango for breakfast and started work. A friend came round for lunch and we talked about a paper we’re working on. Tonight would normally be choir, but we had the concert last week so there’s a break. In…

To come briefly back to genes. I said that natural selection “indexes” the issue above. That’s because it reflects the same underlying process. You can summarize that process in a single picture.

The picture shows something labelled competence. Before modern economic growth the world is a tough one, where high competence in various dimensions is rewarded and low competence is punished. That is true both at individual and collective level, if we think of “competence” as something cultures can have. The advantage is that this slowly pushes individuals and cultures to a high level of competence. Indeed this is what eventually produces the takeoff into modern economic growth. The disadvantage is that this world is particularly tough on the incompetent. After modern economic growth we are in an abundant world, where payoffs are more equal. This is not fundamentally a policy decision, though policy affects it. There is simply more to go round. That increases the welfare of the least competent. But the loss is that it removes the selection pressure. We can see that in genetics. We can also see it in the ethically more important aspect of cultural change.

There is much more about the predecessor civilization in my book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present. It’s available from Amazon, and you can read more about it here.

Tobias is not responsible for any of the content in this post, though.

Assuming there are no big effects on some specific disease; and assuming that the overall effects are no bigger than they seem to be from research today.

I think this is in Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom.

Gah, my eyes go wide when I see these inchoate fears that I nurse explained through such diverse examples, then pulled together into a simple graph. Thanks for helping me bring these thoughts into forms that can interact with the rest of my thinking.

In your mind, what are the realistic hopes for creating new cultures? (Feel free to reference your book; I have a copy.)

Thought provoking and insightful, as ever. Recently read a history of the Jesuits, and there's a constant struggle in the Order between the mystical/ecstatic and obedience/regulation - freedom vs structure. There are things that can only be experienced by discarding rationality and conscientiousness, and that idea is deeply embedded in the New Testament. It feels like a reaction against it explains the strength of the revulsion some atheists feel regarding Christianity. But in the context of the Jesuits, the two opposed impulses seem intertwined. I suppose, with reference to your essay, you might say that sometimes freedom doesn't just mean ease and shallowness (mystics don't live lives of thoughtless luxury), and that it has its own strength that order can't replicate - but that those responsible for the structures that lead people to a fierce desire to discard structure always fear the disintegrative power of that impulse.