Your society has an interest in lying to you about altruistic behaviour, exaggerating its personal benefits to yourself while downplaying its costs. We also all have an interest in publicly deceiving each other about this, even perhaps at the cost of sometimes deceive ourselves. Sure, I want to be selfish, but I don't want to go around saying "selfishness is good"! That'll just make you selfish and nobody wants that, except you maybe.

This is very different from knowledge about the physical world. There we collectively benefit from getting the facts right. From early times, complex societies supported astronomers, because astronomers could help us learn about the seasons and know when to plant stuff. They also supported people who said things about society, like priests and orators. But they didn’t pay those people to get things right. They paid them to say virtuous things.

Here are four examples of how this collective interest in moral deception plays out.

Participant chat in experimental public goods games.

Divine punishment.

Reason and the passions in classical moral philosophy.

Dealing with the Prisoner's Dilemma in modern moral philosophy.

Economic experiments

In a public goods game, everyone contributes money into a pot, the money is say doubled and shared equally. So if there are four players, and you put a pound in the pot, the players benefit by a total of two pounds, but you only get 50 pence back individually. Everyone does better if we all donate all our money: we’ll double it! But I will do better if I don’t donate my money.

Experimental economists like to run this kind of game, to see what actually happens. We recently did one online. The participants were able to chat to each other before making their individual decisions. Here is a lightly fictionalized example:

1: Hi, what’s best to do?

2: No idea tbh

1: Am I right that if we put in 100 we’ll all get 200 back?

3: Yeah

2: So the best overall return would be for everyone to invest most

2: I reckon we should just go 100

1: I'm up for 100

3: Same

2: OK

2: Submit now?

(100 here is equivalent to a few pounds, the total money available to each person.) Typically, these chats mentioned that everyone would benefit from putting the maximum into the pot. Rarely did they mention that you, individually, would benefit from keeping your own money for yourself. It’s not hard to see why. If you haven’t figured that out, I certainly don’t want to tell you. If you have figured it out, I still don’t want to tell you, because what would that make me look like? Answer: a calculating person who thinks of his own advantage.

Notice that noone is appealing to altruism here. The argument is couched in terms of self-interest, but it is the self-interest of a fictional personal called “we”. Arguments about “we” proceed as if we were all limbs of a single body, or as if we were all going to share our money after the experiment anyway.

And yet, mysteriously, not everybody does donate all 100 of their money. In fact, not even all those who make this argument donate all of their money!

I like this setup because it is the cleanest possible demonstration of my point, in a tiny, artificial world.

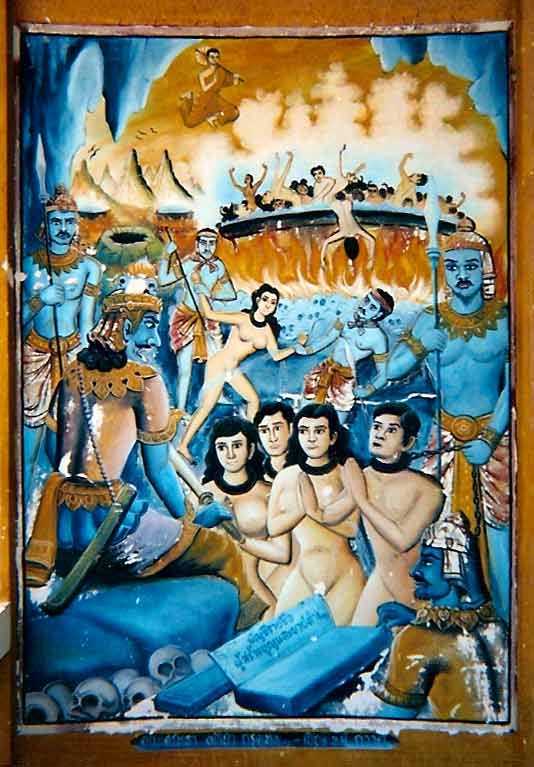

Divine punishment

It’s not just Christianity that has a hell:

Part of what Big Gods do is punish people. But the Christian God was very good at it. The Puritans, in particular, were not shy about pointing out that this gave people powerful self-interested reasons to behave well.

Then shall that most dreadful sentence of death and condemnation be pronounced against them by the most righteous Judge, Matt. xxv. 11, “Go, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, which is prepared for the devil and his angels.” Oh doleful sentence! oh heavy hearing! Whose heart doth not tremble at these things? whose hair doth not stand upon his head?…

Put case—it were certainly known that Christ would come to judgment the next midsummer-day; oh what an alteration would it make in the world! how men would change their minds and affections! who would care for this world? who would set his heart unto riches? who would regard brave apparel? who durst deceive or oppress?

The Plain Man’s Pathway to Heaven, 1601

Classical moral philosophy

The basic way classical philosophers, from Plato up till the 18th century, saw morality was that reason dictated a person ought to behave morally. But his passions might sway him to behave selfishly. In a good person, reason controlled the passions. In a bad person it was the other way round.

Hume turned this all on its head, stating that “reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions”. Since Hume, that idea has developed into a sophisticated theory where people maximize their self-interested utility, using their reason optimally in the service of passions aka preferences. The theory has helped us develop tools like the Prisoner’s Dilemma for reasoning about the relationship between individual and collective self-interest. Not surprisingly, that dismal science continues to be unpopular in public discourse.

The first really serious response to Hume was from Immanuel Kant, who said that Hume woke him from his dogmatic slumbers. Kant’s was a conservative reaction, in the sense that he realized the traditional ideas needed to be put on a better basis to be saved. He came up with a theory in which moral action must be driven by the very purest reasoning, and considerations of welfare simply should play no role. We must simply all follow the Categorical Imperative.

Modern moral philosophy

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is the extreme mathematical simplification of a very old idea. I’ll just draw it here.

In the bottom right cell, we both get a payoff of 2. We would both like to move to the top left cell, and get a payoff of 3. But each of us individually can only make half that move. And we always individually prefer to move down or right, defecting so as to get 4 instead of 3, or 2 instead of 1. Our collective welfare is stymied by our individual self-interest.1

In a way it is extraordinary that it took so long to put such a simple idea on paper. By the time the Prisoner’s Dilemma was formalized as a 2x2 game, we already had relativity, quantum physics and the first computers!

It is also interesting that it took moral philosophers a great deal of time to accept that it is indeed rational to defect in the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Note, this is not a claim that it is rational to be selfish! The players in the Prisoner’s Dilemma are selfish by assumption (or at least, their payoffs are what we see — perhaps they include large donations to each player’s favourite charity). The question is, taking their selfishness as given, how they should act.

One argument against Defect being rational is still current and gets seen among online Rationalists sometimes. It goes like this. The two players in the Dilemma are both rational and have identical preferences. An outside observer should predict that they will both make the same decision. Now, since each player knows that the other is rational, shouldn’t the players also predict that they will make the same decision? So, if I end up choosing Cooperate, you will too, and if I choose Defect, you will too. Well, then I should choose Cooperate!

I don’t find this argument very plausible because it has an obvious flaw. My decision may very well be good evidence for what your decision will be. (That can happen in lots of more realistic situations than the abstract world of the Dilemma. I may have similar visceral reactions to certain options as other people. We may all see the benefits of defection or cooperation in a similar way. There are lots of cases where it’s a good idea to predict that others will act like me.) But my decision can’t possibly cause your decision. The person who decides to cooperate, because then the other guy will too, is like the man who, noticing that whenever he takes his umbrella to work it’s raining, decides to leave his umbrella at home from now on so as to stop the rain.

But why trust me? The argument has spawned a whole field, called evidential decision theory. (Here’s a nice starting point.)

Too much of a good thing

What these cases have in common, excepting divine punishment, is that they push a good argument too far.

In the public goods experiment, the participants will all do better if they all donate their money.

It is true, as classical ethics says, that people’s happiness depends on overcoming their passions. If there’s a single rule for happiness in life, it is “learn to bear present discomforts for future rewards”. The basic structure of human upbringing is teaching us to overcome our mammal heritage, which is continually passing us short-term instructions like “eat more pizza now” or “get in a fight with that idiot” via our dopamine receptors.

It’s absolutely true, and key to the point of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, that the players will do better if they can somehow both cooperate. In fact, any time that we can choose collectively, we choose cooperation! Nobody likes paying taxes, but everybody votes for taxes, because it’s a choice between all being forced to cooperate, and all being able to free-ride.

In each of these cases, an argument got over-extended. The relevant collectives seem to have recruited these persuasive arguments as a way of convincing their members to behave altruistically.

The same collective interest may even leave traces on our language itself. Virtue theorists sometimes argue that a “good man” is just as meaningful a term as a “good axe”. An axe that does what it should is a good axe. A man that does what he should is a good man. I would think of this as another example where a useful descriptive term is being over-extended, so that we can convince each other that a good man is as praiseworthy as a good axe. Another example: the word “we”, and the whole structure of plural nouns and verbs, is also a way to allow groups to reason collectively while concealing their individual differences in interest. Of course, in many contexts it is indeed essential to plan and work as a team. But in some contexts it’s also essential to stop people thinking as if they are not part of a team. The word “we” is the very first example of the famous Roman myth of the body parts.

In that myth, the head tells the limbs that it’s his role to do the thinking, while the limbs do the work and the stomach does the digestion. As that story suggests, often moral arguments are used by the powerful to justify cooperation on unequal terms. Marx made that idea the foundation of his theory of morality and ideology. But although this certainly happens, it is a special case, not the root of the phenomenon. Even our public goods game players, who are all in an equal situation, had a reason to fool each other about what to do. A certain amount of obfuscation is in the general interest.

Lastly, none of this implies that selfishness is the truly rational rule of behaviour. For biological beings, selfishness at genetic level, i.e. kin altruism, maximizes evolutionary fitness. But nothing forces us to be biological fitness-maximizers, and most people probably don’t want to think of themselves in that way.

If you liked this, you might enjoy my book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present. It’s available from Amazon, and you can read more about it here.

I also write Lapwing, a more intimate newsletter about my family history.

The oldest version of the idea that I know is in Plato’s Republic:

You are very kind, I said; and would you have the goodness also to inform me, whether you think that a state, or an army, or a band of robbers and thieves, or any other gang of evil-doers could act at all if they injured one another?

No indeed, he said, they could not.

But if they abstained from injuring one another, then they might act together better?

Yes.

And this is because injustice creates divisions and hatreds and fighting, and justice imparts harmony and friendship; is not that true, Thrasymachus?

Great sense of humor In this piece -enjoyable read.

“Get into a fight with that idiot” encompasses so much of human nature.

Very interesting article, liked it a lot. I do have one small bone of contention though. It’s been shown over and over in iterative prisoners dilemma type games that the most successful strategy is Tit for Tat. It is undefeated Tit for Tat involves initial cooperation followed by mirroring your opponents actions after that. I think iterative games are a better representation of real life strategies as opposed to single prisoners dilemma choices. One thing of note about prisoners dilemma is they are “prisoners”! The authors chose that specific scenario to make their point but most of us don’t get ourselves into the position of the prisoner. The binary choices of people in situations where there is no sympathy for them in their immediate vicinity (prison guards won’t care about your priors) are quite different from most human choices in everyday life.

One can always find special situations where seemingly counter intuitive strategies are called for. Like smothering your crying baby because you are in hiding with a large group and risk being found if you don’t stay quiet.