Sasha Gusev and I had a debate on Twitter, which gave me lots of things to write about. For example, I thought of writing about whom to cancel, since, as we surely now know, everyone has to cancel someone. But in the end I decided to write about this tweet:

That sounds very high-minded. Is it true? It’s good to ask ourselves these questions, otherwise we might end up holding fragile moral beliefs, which sound great but fall apart when challenged.

In other news, I’ve started a second substack, Lapwing. It is more personal and talks about my childhood and my family. If you’re interested in reading about growing up in twentieth-century Britain, you might like it.

My little dog trots through the woods, ears pricked up, eyes shining, on the scent of something. He is supremely alive. What makes him this way, so much more than when he mopes on the sofa at home? He is fulfilling his purpose, doing the one job he was born and bred to do. Murder.

I have two conflicting intuitions. The first is that life is better when it is full of fun, wit, curiosity and joy. Champagne is better than flat beer. The second is point two of the tweet above: everyone is morally of equal value.

This is a real conflict. If some parts of life are better than others, then maybe some lives are better than others.

The universe has value because there is sentience in it. We can imagine a universe without any consciousness, just a big pile of rocks. Perhaps that is not a logically coherent image, because if nothing can be perceived, it is hard to know what it means to say that something exists. (Physicists think that infinite eons will pass after all matter decays. With nobody to count, what’s the difference between an eon and an instant?) The puzzle of consciousness may be identical to the puzzle of existence (I think Hegel1 may have first thought of it this way). In any case, an unconscious universe would have nothing of value.

Humans experience value, good and bad: joy, love, transcendence, comfort, fear, sorrow and tummy ache. We disagree with each other about the details of what we like, but we are surprisingly united on the big picture.

The value-experiences we have are those of evolved beings. We know love because mammals must raise their children and humans must pair-bond. My dog likes killing because he’s a carnivore. The fact that our experiences are created by evolution may be an important fact for ethics: it constrains what an experience is.

In particular, our value-experiences are part of our broader life. We can’t always experience joy, because joy makes no senses without the mundane background it stands out against. There are better and worse lives, and some are dreadful, but the idea of an all-good or all-bad subjective life is incoherent. (Heaven and Hell make no sense, at least taken in that way.) If we think we can imagine such a thing, we are not imagining hard enough, like imagining that two plus two is five.

Once we’ve understood this, we can try to make sense of the idea that all human lives are of equal value. It’s not that all human lives are equally happy. It is better to be a brilliant scholar, athlete and poet than to be a disabled, blind and mentally retarded person. (Obviously. Which would you prefer?) The natural conclusion is that the scholar-athlete’s life is more valuable than the disabled person. This is the conclusion of many kinds of utilitarianism, too: if you think utility is comparable between people, and you count being dead as the same level of utility for everyone, then the life of the scholar-athlete adds more utility. Utilitarians just don’t like to think about this much, but it’s implicit in e.g. the use of Disability-Adjusted Life Years. I want to capture my sense of why that conclusion is wrong.

Sidebar: one answer to that question is kind of political. I myself would clearly rather be the scholar-athlete than the cripple. In a sense, by making that choice, I kill my future disabled self and let my future scholar-athlete self live. But we don’t want to delegate that choice to a third party. It would give them too much dangerous power. So we prevent capricious decisions by insisting all lives are equal; in non-routine, life or death situations, maybe we accept that this rule would be abrogated. But this is not the answer I’ll pursue here. I’m interested in how we should value things, which is logically prior to how we should organize social decision-making.

One part of the answer is a bit similar, though, in that it focuses on the difference between first- and third-party decisions. A person’s life is everything they have. Choosing one person’s life over another is not like picking between two alternative futures for myself. It is ending a universe, and letting another one continue. This is the idea of the separateness of persons. It is no compensation to the loser that the winner’s life will go on. We are locked in separate rooms. This too is a fact related to our evolved nature, as minds housed in separate bodies.

A second part of the answer is related to the Christian roots of the idea of equality: that we are all equal in the eyes of God. (I think the best cite is Galatians 3.28: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.”2) The simplest way to put this is that we are all equally souls, all centres of consciousness. If only consciousness has value, then my consciousness, to me, is all the value that there is. There is a modern, scientific analogue of this idea, which is that all humans are, to a dispassionate observer — say, a Martian ethologist — pretty much alike. This is a consequence of being sexual organisms. You can take two genomes, chop and splice them up, and make a third, viable genome. We are like cars whose parts are interchangeable, down to the smallest detail. As humans, we obsess about our differences; those are real, but their supposed importance is a statement about social organization and social psychology, not about biology. We are all chimps that have put on airs and graces.

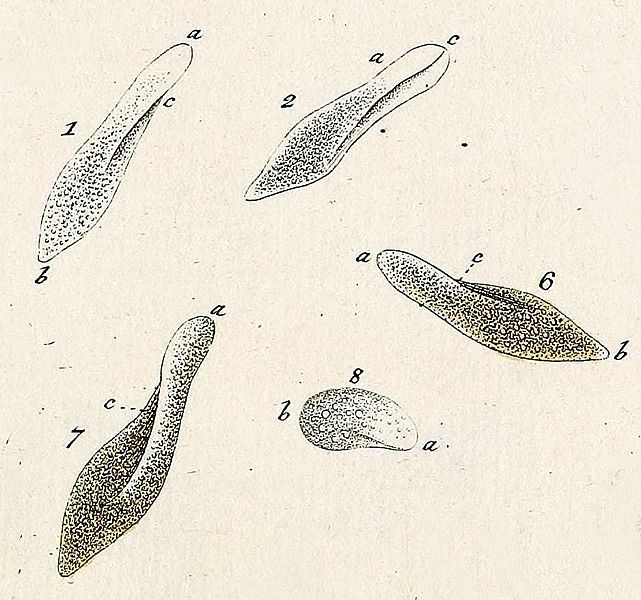

But there is a gap here. The biological similarity of two human organisms does not seem to translate into similarity of experiences. (It’s still much better to be a scholar-athlete than a mentally retarded disabled person.) So now we need to delve a bit more into the true structure of human experience. And observe that we need an empirical answer. You can’t just bang your fist and say “all humans are valuable, dammit!” Because you will then be vulnerable to a thought-experiment in which I gradually alter a human, maybe proceeding up the generations one by one, into our common ancestor with the paramecium. Unless you know what it is about human experience that makes it valuable, you will have to accept that humans are equally valuable with ancestral paramecia. (So yes, this also means that chimps and other animals may have value too; no arbitrary cutoffs at species boundaries allowed!)

I do not have a complete answer to this, and I don’t know that anyone does. (If you haven’t realized, I’m no professional philosopher; I just have to think about these issues, like everyone else, so as to work out how to live.) One thing that seems relevant is our deep opacity to ourselves. We never fully know what our consciousness is; we aren’t aware of many of our sensations. We don’t notice the birdsong until suddenly we do. We discover what we have lost in retrospect; we realize who we are after years of wandering, and never know that our self-knowledge is complete. This is equally true at grand and mundane levels of our experience.

Here are two simple illustrations of this which amuse me.

1. You are at the tiger cage in the zoo. Lost in admiration, you gaze at the fearful symmetry of the magnificent beast behind the bars. What grace! What beauty!

Think how this attitude would burst like a bubble, if the bars were suddenly to vanish.

2. Gripped by depression? Convinced life is worthless? My advice: get jumped by a strangler. You will realize at speed, as his surprisingly large hands close implacably round your throat, the irreplaceable value you derive from breathing.

For some more serious evidence, all 29 people who have survived jumping off San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge regretted their decision as soon as they jumped.

Since we are so misguided about what really matters, we should be sceptical of any claims about whose experience matters more. We may tell ourselves poetry counts for more than pushpin, or that nothing counts but the giddy heights of love and art. (Nietzsche came to think something like this, and I think he did so to protect himself from the awful thought of Schopenhauer, that the joy of the fox is greatly outweighed by the suffering of the chicken. Perhaps this protective barrier collapsed when he met that horse in Turin. By the way, there are effective altruists who have gone the other way and dedicated their life to the welfare of shrimp.) In fact, maybe 90 per cent of the value of life is just from drawing breath.

That is a pretty uncertain foundation to be sure that everyone is of equal value. (There are certainly cases it doesn’t cover. Nothing here really addresses coma patients, or the unborn or newborns, for instance.) But it’s where I have got to. This hasn’t been an argument about policy and who should be weighted more in Health Service budgets, though obviously those questions depend in part on answers to this one (my answer suggests a form of contractarianism, I guess). It’s about where the value in lives resides, irrespective of how society is organized. I treat people as of equal value because of our own deep uncertainty about what matters. As this argument is rather incomplete, I will end with an appeal to authority:

The day of an ascension, the

minster stood opposite, it fetched

a little gold across the water.

The conversation was about your God, I spoke

against him, I

let the heart that I had

hope:

for

his highest, death-rattled,

lamenting word —

Your eye looked at me, looked away,

your mouth

spoke words to my eye, I heard:

We

don’t know, you know,

we

don’t know

what

counts.

— Paul Celan, from The Stork hotel, Zürich

If you liked this post, you might like my book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present. It’s available from Amazon, and you can read more about it here.

You can also subscribe to this newsletter (it’s free):

This is going to be a pretentious post. Deal with it.

There are probably non-Christian religious foundations for the same idea, but I don’t know them.