The challenges

Is it OK to smack, spank or physically punish your children? Billions of parents care deeply about this question. But answering it is very difficult, because it comes with horrible methodological problems.

Obviously, there is a huge problem of reverse causality. Suppose children who are regularly spanked are naughtier. Did the punishment make the kids worse? Or did the bad behaviour get them spanked?

A conventional workaround might be to look at individual children who start to get spanked more, and ask whether they get naughtier. That won’t work here, because the reverse causality just carries over. Did they get naughtier because they were spanked more, or vice versa?

Spanking might tell you about not just the child, but also the parents. Who are most likely to spank their kids? Probably not upper class professionals. Probably, people who haven’t ingested the conventional wisdom that spanking is bad. Perhaps, people who just don’t care. Any of these groups will treat their kids differently in other ways. So now you have omitted variables, which will be hard to measure and control for.

In particular, suppose that in the twentieth century physical punishment has become déclassé so that only ill-informed and/or uncaring parents do it. Then it will be associated with all the other foolish or careless things they do. But in other times or places, where physical punishment is recommended by advanced authorities, it could have the opposite association! This is sometimes called cultural normativity in the literature.

Here’s a specially tricky version of omitted variables. We want to evaluate parenting strategy, but when we measure punishment, it is typically an outcome. Suppose the world is like this: some parents consistently use physical punishment. Their children know this and are almost never naughty. Other parents use physical punishment, but inconsistently, and their children are naughty more often and sometimes get spanked. In this world, the strategy “use consistent physical punishment” works. But also in this world, episodes of actual physical punishment are positively associated with naughty children. Since the literature often measures punishment by asking parents whether e.g. they punished their kid on a given day, it might have this problem. (It is a bit like the rules versus discretion problem in central banking.)

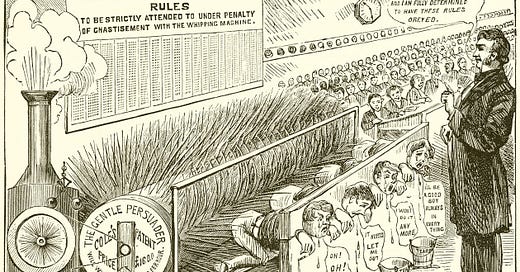

There is a continuum of physical punishment. Here is a picture:

Everyone agrees that the right hand side is violent child abuse. And note, even serious violence is often framed by the perpetrator as punishment (think of the butler in The Shining who tells Jack Torrance his wife and child “need a good talking to”). The question is where to draw the line of acceptability. One answer is on the extreme left: physical punishment is always bad. Now imagine running a regression where you put the entire continuum as the independent variable. This answers the wrong question! You will be estimating the effect of a mixture of actions, some of which we all know are harmful. But we want to find out the effect of actions on the left hand side.

Maybe we can separate out different levels of punishment severity. Sure, but how to measure it? You will probably rely on the accounts of the parents themselves. But violent parents may downplay the severity of their physical punishment. If so, your less-severe category will contain some miscategorized cases, and again, you’ll be estimating the effect of a mixture.Measurement is also a problem when researchers ask people to recall their parents’ punishment. A person who is depressed may take a more negative view of how their parents treated them; a violent person may blame his violence on his parents.

By now, alert readers will be thinking about randomized controlled trials. But ethics committees won’t let you randomly assign some parents to spank their children (and what kind of parents would agree to take part?) Instead, you could try a RCT of a program to stop people spanking their children, perhaps by showing alternatives. Right, and some have been done, but there are problems. First, who will sign up for that trial? Certainly not a random sample of parents. Maybe parents who suspect they have problems with discipline. So now you have selection bias.

Second, the programs typically have many components: they might teach new parenting skills, or increase parents’ self-confidence. Few programs just consist of the lesson “don’t spank your children”. So it is hard to tie any improvement in the child’s outcomes specifically to less physical punishment. There’s also a great risk of Hawthorne effects: struggling parents may react well to any kind of help or attention. And maybe that means the programs are worthwhile! But it doesn’t tell you much about whether spanking is bad.

Kids vary a lot, and they might vary in how they respond to punishment. One is quiet, but gets easily upset by criticism. Another gets angry and defiant, but moves on quickly. And parents might know their children, and choose their parenting strategies appropriately. Here’s a simple model of how that can mess with the science. Suppose parents always choose the right strategy: they punish physically if their child will react well to that, and use another approach if that works better. Now suppose you target the spanking group with a treatment that forces them to change strategy. That will make their outcomes worse! But that wouldn’t mean spanking is better in general. The correct answer is “it depends”. This example shows that even a well-executed RCT may not estimate anything useful, if parents make choices based on factors the scientist doesn’t observe.

What should our dependent variable be? On a utilitarian view, we care about three sets of people: the child himself, the parents themselves (to see why this might matter, consider the example of a physically violent adolescent) and everybody else, including other children the child interacts with. All of these are affected by both the physical punishment itself, and by any changes in the child’s behaviour. Consequences to any of these groups may be long-run, so we need some plausible proxies. A common one is the child’s “externalizing behaviour”, which is jargon for being naughty. If punishment makes a child naughtier then it is failing in its primary purpose, and probably won’t have any other good effects. But translating this into a measure of welfare is going to be hard, and externalizing behaviour is especially subject to the reverse-causality problem.

What practical outcomes will flow from the research? You might give advice to parents, like “don’t use smacking, try this instead!” But the people who seek advice from researchers, doctors, or government agencies are not a random sample of the population. They might be the type to read parenting blogs, for instance. If they use physical punishment, it is more likely to be on the left hand end of the continuum. So even if you’ve fixed the problems above, and got an accurate estimate of the effect of smacking across the whole population, that is not guaranteed to be useful for the people you are actually talking to.

Or you might take a more coercive route, and impose a legal ban on physical punishment. But notoriously, the effect of a legal ban on X is not just the effect of X times minus one. (Bans on drugs are a famous example.) What happens inside families is hard to monitor. Parents who need help may be afraid to ask for it if they risk punishment. And you’ll be giving the state new powers to interfere in family life….

Publication bias is a thing. Null results might not be seen as interesting. That in turn affects researcher incentives. Research with parents and children is time-consuming: doing it and coming up with “nothing” may hurt your career. The complexity of the required research designs gives researchers a lot of levers to pull (“degrees of freedom”) so as to get that p value to 0.05. There’s also a specific risk of ideological publication bias here. When the literature on smacking is published in journals like Child Abuse & Neglect and Journal of Family Violence, then you might worry that the scholarly community has prejudged the issues.

These are scarily hard problems. This question of ordinary human behaviour makes bigger ones — estimating the effect of democracy on growth, or the genetic heritability of height — look easy by comparison. So, how has the literature dealt with these challenges?

Mmmmm.

The history

Here’s an idealized story of how social science affects policy. Researchers investigate a social issue, perhaps after activists have drawn attention to it. Starting with uncertain conclusions from imperfect methods, they refine them until a tested consensus has formed. Then, they take part in public debate, lobby politicians, and eventually help to form policy.

Researchers refine their methods until a tested consensus has formed. Then, they take part in public debate, lobby politicians, and eventually help to form policy. The actual history of corporal punishment research looks like this, except in reverse.

The actual history of corporal punishment research looks like this, except in reverse. The UN Convention of the Rights of the Child was signed in 1989. Article 19 calls for states “to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence”. Does this include physical punishment? That’s not clear. But by 2006 the Committee on the Rights of the Child, which oversees implementation, formally states that it does. In fact, by 1995 the expert committee already believed that corporal punishment was incompatible with the Convention. And lawyers were making this argument even earlier. Price (1984), addressing the draft Convention, calls freedom from corporal punishment “one of the human rights of children”.

At this point, the research base was utterly inadequate for these conclusions. Researchers had not adequately dealt with a single one of the problems above. We are in a world of bivariate correlations. Here’s one of the research articles cited by Price, written in 1978. I don’t belittle the contributions of early researchers on important topics, but this article focuses only on “severe” punishment — so, only looking at the right hand side of the punishment-to-violence continuum. It makes its case by correlations between violence and strict child-rearing at cross-country level, and with anecdata like:

O’Hanlon (1975) suggests that the violence in Northern Ireland, exemplified by the Irish Republican Army's terrorist tactics, can be traced back to the brutal child-rearing practices of the tense, distressed, and remarkably aggressive parenting of the poor Irish Catholic mothers and fathers.

I’m no Fenian, but…. And the author dismisses concerns of reverse causality like this: “There may be a grain of truth in this argument, but I seriously doubt that a child is born bad.” (1978 was probably about the high point of blank slatism.) Sure, no child is born bad — that’s a misuse of the word — but children do vary, big parts of that variation are genetic, and anyway, many environmental causes might make a child “bad,” or badly behaved, before he got spanked.

If you think there is no progress in social science, go read that article. It would be unpublishable today. (Update: unless, it seems, you have an FMRI machine. Then you can be at Harvard and produce this kind of dross 🙄.)

Another law paper, from 1998, gives this explanation:

… a child, like any human being, experiences rage and indignation upon being struck, but cannot express these feelings because of the risk that there will be further punishment or withdrawal of adult approval and love. Repression, however, is only a momentary solution. The anger must go somewhere and it does…. a few of the more pernicious [effects] are aggressiveness, lack of empathy, and a tendency toward either authoritarianism or blind obedience.

Back then, you see, people took Freud seriously! Later, the author asks “Could there be a link between the commonly experienced pain of childhood corporal punishment and the surreal brutality of the Nazis or the Khmer Rouge?”

The same article concludes “there is an empirical and theoretical basis for concluding that the effects of [corporal] punishment are not only not helpful, but are profoundly deleterious.” In 1998, this was not even close to true.

So, the international structure which would work to ban corporal punishment was set up far in advance of any credible evidence. That structure also provided a set of levers that social scientists could pull. A 1995 review article of the CRC wrote “Social scientists who are conducting research or working in the field have the opportunity to contribute toward children’s well-being”.

The UK New Labour government placed great emphasis on “evidence-based policy making”. To cynics, this sometimes seemed to work in reverse: first the policy was decided and then there was a process of “policy-based evidence making”. If a well-funded international bureaucracy is in the market for work to support a belief that is already very widespread among right-thinking academics, policy-based evidence making is a risk.

The state of play

In fact, researchers seem to have been astonishingly slow in dealing with even the problem of reverse causality, the first and most basic of the long list above. In Elizabeth Gershoff’s 2002 meta-analysis of research on the effect of corporal punishment, almost 60% of the studies were simply cross-sectional correlations. This is at least a generation after research began.

Simplifying a lot, the history since then is an ongoing ping-pong between boosters of this research, most notably Elizabeth Gershoff, and skeptics, most notably Robert Larzelere. Gershoff writes a meta-analysis; Larzelere responds with a critique; Gershoff retorts with more analysis. I am more sympathetic to Larzelere’s point of view, but on its own terms, this is science working as it should: humans with their own biases and agendas come together in an arena governed by commonly accepted meta-rules of evidence and argument.

Social science: activists versus experts

How should social scientists think about what we are doing? Here are two viewpoints, which are both wrong. The first is that social science is activism. The demand for “objectivity” and “neutrality” is a strategy of power to prevent radical social change. Instead of being objective, social scientists should be committed radicals.

The problem is that the boosters are persistently over-confident about what they have shown and in their recommendations to policy-makers. For example, here’s Durrant and Ensom’s 2012 review:

Physicians familiar with the research can now confidently encourage parents to adopt constructive approaches to discipline…. [“constructive” clearly means “no physical punishment” in this context]

But a few paragraphs later they say

prospective studies… controlled for parental age, child age, race and family structure; [long list of controls in other studies]… These studies provide the strongest evidence available that physical punishment is a risk factor for child aggression and antisocial behaviour.

I’m sorry, but if that is the strongest available evidence, then you are nowhere near the threshold for telling physicians what to recommend. What these studies are doing is starting with a child, measuring the level of physical punishment plus some controls, waiting one or two years, then measuring e.g. child aggression. The obvious risk is that child aggression later correlates with child aggression earlier, child aggression earlier leads to more physical punishment, and you have reverse causality. Controlling for early child aggression would solve this if you could do so perfectly. But of course, you can’t! Aggression is going to be measured with a ton of noise. The same for the other controls: any experienced social scientist knows just how difficult it is to control for the subtle differences between families which may make some child better or worse. (Even controlling for something as “simple” as poverty is incredibly hard — poverty has many dimensions, people mis-state their own income, and so on.)

As Larzelere et al. (2010) showed, using this methodology would lead you to conclude that ritalin and psychotherapy both cause ADHD. And note that these papers still haven’t dealt with any of other challenges I listed above!

It’s worth just looking at an experimental paper, since true experimental evidence would avoid several of our challenges. Beauchaine et al. (2005) is cited in a Gershoff et al. (2018) literature review as experimental evidence for the effect of spanking:

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the Incredible Years intervention for young children with behavior problems found that treatment effects were significantly mediated through a reduction in parents’ use of spanking.

Now a mediation analysis just means that you ran the RCT, you see it affects parents’ use of spanking, and when controlling for parents’ use of spanking, the effect of the RCT on child outcomes is smaller. But this mediation analysis is not itself a randomized trial! The RCT could have affected many other things along with parents’ use of spanking, and any of these could have changed children’s outcomes. In fact, if we look at the original paper:

the Incredible Years Parent Training Program… teaches parents child-directed play skills, effective parenting skills, communication and problem-solving skills, strategies for coping with stress, and ways to strengthen children’s prosocial behaviors and social skills.

Sounds like a great program, but on its own account it is doing much more than one thing. Not surprisingly, the evaluation statistics are complex and involve pictures like this:

I have a sceptical rule of thumb: when the causal diagram is more complex than the reader can understand, then reality is more complex than the diagram can capture. And of course more complexity means more possible models, means more possibilities for deliberate or inadvertent p-hacking. This paper does not provide strong evidence and certainly not causal evidence about the effects of spanking.

Here is an imperfectly informed summary of how the science to date has dealt with the challenges above.

Reverse causality. Acknowledged in the literature. Imperfect attempts to deal with it via longitudinal studies, experiments and matching methods.

Omitted variables. Understood in the literature, but dealt with by adding in controls. This strategy is probably doomed to failure.

Cultural normativity. There’s an on-going subliterature.

Rules versus discretion. Occasionally acknowledged (e.g. Beauchaine et al. 2005, “good discipline is hard to observe…parents who discipline well seldom have to apply sanctions”) but I know of no attempts to deal with it.

Continuum of punishment. Regularly discussed and acknowledged. Good work tries to differentiate severities of punishment; debate continues, e.g. here and here.

Problems of recall are understood. Prospective studies are considered the gold standard.

Selection bias and many components in experimental studies. Rarely discussed.

Choice of parenting strategies. There’s awareness that children may vary, but little understanding of how strategic parenting choices throws up difficulties for causal inference.

What’s the dependent variable? I’ve never seen a systematic theoretical discussion of how to evaluate the welfare consequences of smacking, or of any potential tradeoffs. Researchers do acknowledge that, e.g., some parents face limitations on time or resources.

Selection into who listens to advice. This is a really hard problem and unsurprisingly has not been much discussed. The attitude of most researchers is that advice should be spread as widely as possible. That’s unlikely to work, because parents’ attention is finite (and some pay more attention than others), and practitioners likewise do not have infinite resources to communicate anti-smacking messages.

Also, there is startlingly little research into the effect of bans. That’s surprising because surely many schools, school districts etc. must have implemented bans in recent years. Shouldn’t someone have run a difference-in-difference analysis? (This cross-national paper has good data but inadequate methods, which is typical for the British Medical Journal. A smart econometrician could do better. Update: looking more closely, even the data is inadequate, it’s just a fairly ridiculous cross-sectional regression. Whenever I want to feel good about the work real social scientists do, I look at what medical journals will publish….)

Publication bias. To their credit, Gershoff et al. (2016) look for signs of publication bias using statistical tests within the sample of published studies. But I haven’t found any study that systematically seeks out unpublished work. Seems like an opportunity for a contrarian graduate student.

Theory and practice

Here’s an interesting question: why aren’t there any experimental interventions which simply encourage parents not to smack their kids? (I haven’t found any: if you know different, say so in the comments.) It is interesting because it gives me two opposing thoughts.

Yeah, why doesn’t someone just do that? It would be ethical and simple.

It’s obvious why programs don’t do that! Just saying “don’t smack your child” isn’t going to help a struggling parent. You need to teach them a bunch of skills and alternative strategies.

Thought 1 is my internal social scientist speaking. Thought 2 is how I reckon a practitioner would respond. If thought 2 is right, then perhaps practitioners are thinking differently from researchers.

The implicit theory of social science is that there is a true model of how the world works. Ordinary people don’t know the true model, but the scientist can find it out by empirical research, and then tell them.

This theory works well for, say, astrophysics. It’s not obvious that it works well for child behaviour. There may be no simple model that describes how children behave, more accurately than individual parents’ understandings about their individual children.

Practitioners seem to place their faith not on telling parents “do X”, but on teaching them skills which will enable them to make better choices for themselves. It’s as if practitioners don’t believe that they themselves possess the true model. They have to delegate to parents, and so they try to give them helpful tools.

Evolutionary history

There is a puzzle for opponents of physical punishment: if it is bad for children, why is it almost universal throughout recorded history? We usually expect practices that harm your own offspring to be selected against. Parents everywhere feed their children and teach them basic skills. What makes punishment different?

One answer given by anthropologists is that actually, some societies don’t do much physical punishment. These are hunter-gatherers, who are usually not just egalitarian but relaxed in their childrearing practices. On this account, family violence reflects the growth of stratified, complex civilizations — and the inherent violence and inequality of those societies. “Corporal punishment of children is a conscious or unconscious way for parents to train their children for a world full of power inequality,” say Ember and Ember (2005):

If the child fears those who are more powerful and acts meek and subservient, he or she may be less likely to get into trouble and more likely to be able to get and keep some kind of a job.

The cross-cultural association between social inequality and corporal punishment is indeed strong, although it can equally be redescribed as an association of corporal punishment with any serious social complexity. How you line up on this question will depend on how you valorize Spartans versus lotus-eaters.

More importantly, the argument is hard to square with the claims of the research above that corporal punishment makes children less obedient, not more. The psychologists say that physical punishment backfires. The anthropologists argue that it doesn’t, though they may deprecate its effects. One of these two groups must be wrong, or there must be something specially punishment-resistant about the modern Western children studied by psychologists.

Reflections

The goal of this article is not to make you buy a cane. Arguments against corporal punishment go back to the Romans, and have been widespread ever since Erasmus. Contrary to stereotype, many Puritans were against corporal punishment and recommended kinder methods of discipline. The difference between those arguments and the modern literature is that the old ones were not posed as absolutes, based on universal scientific laws. They were written as advice, and typically had caveats. Erasmus himself, who wrote passionately against corporal punishment, still allowed it a limited role as a backup:

And if we can not profite by monicions, nor prayers, neyther by emulacion, nor shame, nor prayse, nor by other meanes, euen the chastenyng with the rod, if it so require, ought to be gentle & honeste.

My message for social scientists is first that they should show more humility, be aware how hard it is to write down the true model of complex human interactions, consider that actors in those situations may have knowledge that the scientist lacks, and avoid the temptation to take shortcuts.

Why is the United Nations trying to deciding how parents bring their children up? We wouldn’t expect the American Academy of Pediatrics to weigh in on international diplomacy.

Second, at both individual and institutional level, they need to preserve some basic independence and capacity for critique. When large groups of the virtuous are united in belief X, then there must be institutional room for those who disagree. When powerful institutions start to codify belief X, the first question of the social scientist should not be “how can we jump on this bandwagon?” (A better question might be: “why is the United Nations trying to decide how parents bring their children up?” We wouldn’t expect the American Academy of Pediatrics to weigh in on international diplomacy.)

In practical policy terms, pushes for national or even worldwide bans on smacking have got far ahead of the evidence, and should be actively opposed until the science is much more solid.

My message for parents is the obverse of these points. Even experts who sound very confident may not know more than you do. Your own knowledge, of yourself and your child, deserves as much consideration and attention.

I also think that we should extend the same consideration to other parents. Readers of this blog probably don’t, in the main, smack their kids. Some people not only smack their kids but are physically violent to them, which we all agree is a crime. But some parents do smack their kids, but aren’t physically violent — unless we prejudge the issue, like many researchers and legal scholars, by calling everything on the continuum “violence”. Some questions to ask yourself in considering this third group are: have you been in their shoes? And are you sure you know best?

The Puritans and other modern parents get a fuller treatment in my book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present. It’s available from Amazon, and you can read more about it here.

I also write Lapwing, a more intimate newsletter about my family history.

“tense, distressed, and remarkably aggressive parenting of the poor Irish Catholic mothers and fathers.”

it’s like he met my forebears

Making yourself useful DHJ I applaud

I can’t speak for Smacking bans elsewhere but was given to believe the ban here in NZ was a mere change to close a “reasonable force” legal loophole in cases of child deaths/cripplings, and doesn’t give scope to prosecutions of parents whose children are intact.

So ban away, poke that intrusive govt right in

We’re waiting eagerly for Momma KPH’s book on Punishment

I think this is missing the main point. We know since Skinner that punishment, not just corporal punishment, doesn't work. It doesn't work because it is aimed at reducing a certain behaviour, and that's difficult to target. The schoolmaster may flog children for not doing their homework, but the children will learn to avoid school despite the schoolmaster's intentions. Reinforcement (positive or negative) of desired behaviours is more effective.

As a side note, I'm also missing an obvious response to the evolutionary argument. We like sugar although it's bad for us. Not much mystery there, though. Perhaps the dangers early on were so great, and behaviour less complex, that corporal punishment was selected for. If the child needs to learn not to go out of the cave at night because a bear will eat it, any method will be fitness enhancing. Our caves have doors with locks, and no bears roaming the staircase.