How should social scientists think about what we are doing? Here are two viewpoints, which are both wrong.

The first is that social science is activism. The demand for “objectivity” and “neutrality” is a strategy of power to prevent radical social change. Instead of being objective, social scientists should be committed radicals.

This view is associated with the kind of qualitative “research” that RealPeerReview pokes fun at on Twitter. Its end result is to make the writer’s political virtue an excuse for weak research design. Hey, I haven’t really proved my point, but who cares, because you agree with me anyway! The next step to hell is that you become an activist, which is fine, and demand that funding agencies sub you for it, which isn’t. Congratulations, you are now a trustafarian.

The social-science-as-activism view is mistaken, but it isn’t a big problem, because most research that comes out of it is so bad that it doesn’t affect anything. It’s a way to occupy people who are incapable of useful employment. In the nineteenth century, they might have been vicars. At least they’re not on the streets. There may be some cases where activist scientists have done major harm – Stephen Jay Gould perhaps – but not many. (History-as-activism is a dangerous poison, but that’s out of scope.)

The other view is really the opposite. Social scientists are experts. They’re objective. While politicians peddle their rhetoric, and ordinary people are misled by conspiracy theorists, only we have access to reality. Follow The Science!

Something like this view is held, more or less articulately, by most social scientists doing research that matters. It encourages us to be scientific. There’s a lot to say for that, because hey, social science really can discover things, and it helps if we follow scientific methodology, develop falsifiable hypotheses, run appropriate statistical tests and generally keep our noses clean. (Like, check out this paper. It measures the in-breeding coefficient of European monarchs, and shows that more in-bred monarchs actually performed worse as rulers. Super cool, and careful and rigorous. Sorry, carried away, back on topic.)

So if there’s nothing wrong with trying to be scientific, what’s the problem? The problem is kidding ourselves that we’ve succeeded. Put at its naïvest, this view thinks social science is like physics. In physics – I know this is itself an over-simplified story, get off my back, historians of science – the phlogiston theory and the oxygen theory had a big fight, and eventually oxygen won because the data supported it. Settled physics won fights by fitting the facts.

Social science of any importance will never be like that. This is because social science fights involve the whole of society. Which system will work best, capitalism or socialism? Who should educate children, the church or the state? The answers to these questions affect people’s interests, and they will pay a lot of money to get the answer they want. Physical science makes people money by being right: you really can use relativity to position your GPS satellites. Social science benefits people sometimes by being right, but also… for other reasons, and sometimes those other reasons dominate. That is why throughout the nineteenth century, political economy “proved” (perhaps rightly) that socialism would be a terrible idea and (maybe less convincingly) that state support for education was a dangerous innovation.

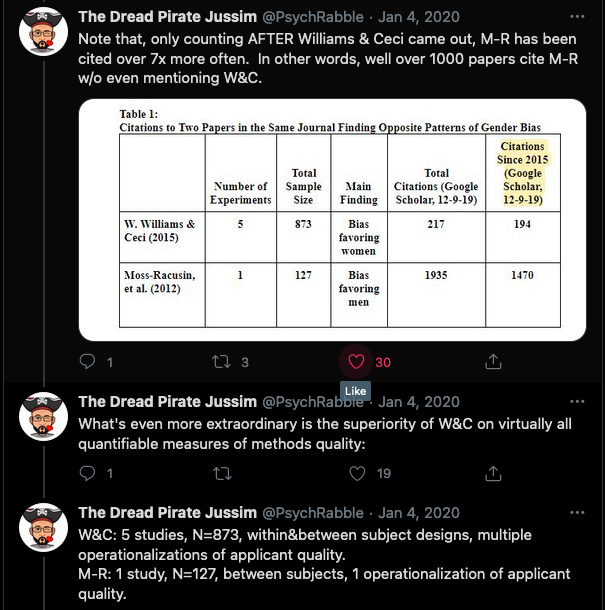

Social science that matters changes social organization – partly, by elevating people who benefit from its world view. In this way, it creates vested interests in maintaining that view. For example, the rise of feminism over the past 60 years has many reasons, and social science has played some role, for instance by IQ researchers showing men and women are basically equally smart. Well, now we have many relatively powerful women – not 50% of powerful people, but more than if feminism had never happened and we were still in the 1950s. And to varying degrees many are convinced feminists. Do they want to hear research that challenges their preconceptions? Now read on:

(Here’s more detail from Lee Jussim.) Notice, this kind of bias can happen even if every author is trying their hardest to be a good scientist! The “expert” picture of social science is right on the micro level, but misleading at macro level, because there is no unbiased filter. What gets published and cited reflects what society wants to hear.

To be more specific: all sciences have biased filters, i.e., old farts in departmental chairs. Hence Max Planck’s famous remark that science progresses “one funeral at a time”. But the physical sciences have a way of correcting filter biases via reality. If you want funding, your rocket had better fly. In the social sciences, there are equally strong social forces exacerbating biased filters. (Maybe that is why, in Soviet Russia, physical science survived relatively well, while social science degenerated into a cloak for the status quo.)

So how should we think about the social scientist’s role? I am groping towards a more realistic view, which balances the “activist” and “expert” extremes. Like it or not, social science is a field of social conflict. We enter the lists in support of one side or another – sometimes supporting the status quo, sometimes perhaps seeking to overturn it. Behind rival theories, there are broader social forces. But, like the knights of yore, we fight by the rules. Or like advocates in a courtroom, we must represent our clients’ interests, but within the limits of professional ethics. You can’t just make stuff up. You have to formulate and test a precise hypothesis. You’d better watch out for p-hacking and the garden of forking paths. Qualitative researchers, you can’t just cut sentences in half to make a point. In short, we practice the micro-level virtues of science, without kidding ourselves that this will ever make us a body of experts fit to hand down wisdom from above. A long-standing idea of the Enlightenment, in its Anglo-Saxon incarnation, is that open societies solve their problems, not by calling in disinterested experts, but by the clash of competing interests on a reasonably level playing field. My view, call it the “advocate” view of social science, fits into that tradition.

If you liked this content, then I would love you to do three things:

Subscribe to this newsletter. It’s free, posts are occasional, and subscribers make me happy.

Share Wyclif’s Dust on social media. This newsletter is a new venture, so by telling your friends and/or followers, you’ll be doing me a huge favour.

Read about the book I’m writing. It’s called Wyclif’s Dust, too. You can download a sample chapter.

Thank you.

May I offer a more demanding ideal?

Humans cannot be unbiased, but minimizing bias is a vocational duty. Don't just play by the rules, adopt the spirit of the rules and seek to be as unbiased as you can. Go further: don't just temper your biased impulses, accept the depth of our ignorance. Cede your ground enthusiastically to the data! Learn to enjoy it. I hope I can.