Temple monkeys

If you visit a Hindu temple in Jaipur or Bali, you might be accosted by a monkey. It might grab your snack, sunglasses or iPhone. If you resist, it might bite you. On the positive side, you may be able to trade your stolen goods back for a banana or a bar of chocolate.

The monkeys are an annoyance and maybe more: there is a risk of zoonotic diseases spreading from the common contact between human and non-human primates. But they’re sacred; grey langurs are known as Hanuman langurs, after the Indian monkey god. They can’t be hunted or killed.

In modern times, the immunity of the langurs has led to some strange practices. In one part of India it is possible to hire men with tame monkeys to drive out the wild monkeys that are causing you trouble. No human may drive away the intruding monkeys, because that would be an attack on sacred beings, but if your trained monkey attacks them, that is between monkey and monkey and, with a little lateral thinking, it can be claimed that no human beings are involved.

Desmond Morris, Monkey

By feeding his monkeys, you honour Hanuman. They’re a hardy species, everywhere in South Asia. Poor villagers throw stones at them, because they eat their crops. But around temples, they are protected. Sometimes they even become tourist attractions themselves. In Bali’s Ubud Monkey Forest, an area surrounding three temples, tourists have been banned from feeding bananas to the monkeys, who became “too fat and aggressive”.

I live on a hill, or what passes for a hill in Norfolk. It’s also a steep social gradient. Up the hill are pretty townhouses behind distinctive flint walls, some with 14th century basements. Below me, there is a post-war block of council flats (social housing, for non-UK readers). The buildings themselves are pleasant and sturdy enough, and most of the residents are ordinary people. But there always some exceptions. The residents at number 11 on the top floor used to get drunk and throw their vodka bottles down on to the street, where they would smash. The chap beneath them didn’t get much sleep until they were finally evicted; various housing charities appealed against that decision, because it would make someone homeless.

Then there is the guy living in one of the garages underneath the flats. He thinks of himself as a graffiti artist. He regularly tags the local area. Occasionally he makes his mark on the flint walls of the nice houses up the hill, but more often he just gets the council houses. Neither his style nor his message are sophisticated: he draws hearts, smiley faces, CND signs, and Yin-Yang symbols. Perhaps he’s hoping to bring love, joy, peace and balance to the world. In one of the nice houses lives an artist. She is in her eighties; her son is just back from Berlin and has started hosting his own vernissages in the annex. She gets graffitied too, but she lets it stay on there. I suppose she thinks it’s creative. The garage guy, so my council-house-goings-on contact tells me, is 64. Recently the police were round: he had started a fire in his garage.

In the back row of council flats, there is usually a flat where someone sells drugs. People hang around on street corners, wearing hoodies in all weathers. The consumers go to a nearby piece of woodland, with a trail going along the side of the river, where I like to walk my dog. It’s a quiet and sheltered place to take drugs. Some of the drugs have a laxative effect, so they bring toilet paper. Afterwards they leave the used sheets by the path. Sometimes they also leave needles.

The drug trade has to self-regulate. The way this works is by people screaming at each other, usually with swearwords. Usually one person backs away while the other person screams at them until they are out of the area.

There are hostels in the area. One is run by the local Quakers. Others subsist, I guess, on council money — not necessarily the local council, because there’s a market of sorts in emergency accommodation. London councils with a statutory duty to house someone will find a cheaper place up North in, say, Derby. I don’t know if they use my town for this too. In the morning, one place offers food. Little knots of people cluster about the door, waiting for them to open. On their way there, they swagger down the street. A tough attitude is a necessity to scare off predators: police protection doesn’t run this far down the social scale. Men who walks as if they own the street probably don’t own much else. So I tell myself.

I’ve never felt threatened where I live. If there is violence, it’s not directed at people like me. It’s hard to say why I am bothered by the sound of screaming, or the sight of a crackhead doing his jittery run-walk to score.

Then there are the drunks. I don’t mean the late night groups of students commuting to, then from, the pubs down the road, making boisterous and braggadocial sounds. I mean the ones with a can by 10 in the morning, squatting in small groups outside their hostels or halfway houses. The cans go everywhere. The local park has a bin every ten yards. That doesn’t make any difference. It has a public toilet, for that matter, which also doesn’t make any difference because the bushes are more convenient.

At the top of the hill is the church. Most of the gravestones have been removed, perhaps because it was too expensive to cut the grass between them. They used some of the fragments to edge the gravel path. Now people go round the back to take drugs, drink and occasionally deal. They leave food wrappings, cans of beer and energy drink, Rizlas, and again the occasional sheet of toilet paper. Usually they sit by the church walls or on a tomb. A sign implores them not to sit on a raised wooden area, in case it’s rotten and falls in.

I find it soothing to think of these people as temple monkeys. They are an annoyance which we have decided to accept as the price we pay for our beliefs.

The cost of the welfare benefits which keep these people in the only lifestyle they know is not high. That’s not what has put public debt at its highest peacetime level ever in most democracies. The big ticket items are pensions, about £140bn, and healthcare which is also mostly consumed by pensioners, about £170bn. Disability benefits, say, are a smaller sliver, about £40bn last year, though they have risen very fast in recent years. People sometimes claim that levels of fraud are also low. Those statistics come from “accountancy-based approaches” to measure fraud, in other words they take a sample of forms and check that the boxes have been ticked appropriately, in other words they’re bullshit. But no matter how high the real numbers are, they wouldn’t make an appreciable dent in public spending.

But working-age benefits occupy an important place in the cultural imaginary of the welfare state. The pensioners who fill the town’s restaurants nightly, ordering expensive food from broadsheet-sized wipedown menus, would hate to think that the welfare state was just a transfer from future generations to themselves, their generation looting the treasury. It is nicer to take a high-minded view. The welfare state is a great and noble institution. It helps the poorest in society. It protects the widow and the orphan. Images of the Jarrow marchers.

Politics involves norms as well as interests:

The votes for unsustainable debt-funded welfare states come from the interests of pensioners. They were told that the government was saving for their pension. National insurance was a “payment in”. With taxes so high, they felt, they could not afford to save themselves on top. Now they just have their state pension and the free NHS. It sure doesn’t seem like much! Politicians had better not try to take any of it away. Why, just when they took Winter Payments from higher rate tax payers, they faced a ferocious backlash.

But voting on interests alone is not very satisfying. It’s much better if you can tell yourself a story in which you are part of an altruistic movement. For that, at least some social spending must go to “protect the weakest”. That’s the norm.

“Don’t you agree that the welfare state is a great and noble institution?” asked a dear friend of mine, a transparently generous and warm-hearted man.1 We were sitting in his dining room, in a famous, scenic and expensive village with no obvious social housing. I thought of his kitchen with its marble floor.

Temple monkeys!

Maybe you’re offended by this metaphor. Don’t I understand that welfare recipients aren’t monkeys, they’re people?

They are, but I’m not sure that is good news for them. You see, real temple monkeys are basically a contented lot. They live lives of happy thievery. The oldest wax fat in their sins. Your lost mobile phone is their gained banana. They have nothing to worry about, because, as the great Steve Bell put it, monkeys don’t have souls.

Those who I’m talking about, on the other hand, do have souls, which is a great misfortune for them, because it makes them about as unhappy as a human can possibly be. That’s why that other sound from the streets at night, the worst sound of all, is the sound of couples arguing. “Arguing”! Screamed hatred and bitterness. Usually the women sound frustrated; the men sound incipiently violent, hurling the cruelest insults they can think of (imagination is not a good thing here; luckily most don’t have much). They blame the other person for ruining their life, and you can hear that they know they have hopelessly ruined their own. It’s distilled misery.

Maybe that’s what’s so bothering about living around these people, even when you aren’t at risk or threatened or even seriously inconvenienced. It’s the misery in your face. Poverty is nice to imagine. You can think about heroes struggling against “disadvantage” and “exclusion”. Imaginary poverty is Leonardo Dicaprio in Titanic. It’s the Jarrow marchers in black and white. Or it’s Timothy Winters, Lord, amen, who is fine so long as he is imaginary.

Real poor people? Nobody wants to see that.

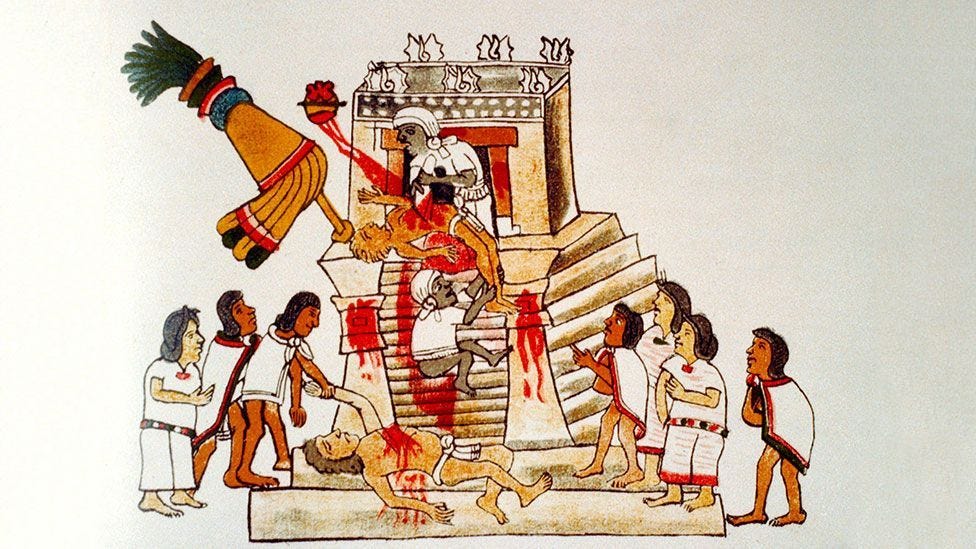

There’s your welfare state, there’s your country, there’s your religion and there you are. Go preen about it, if it doesn’t choke you. It’s human sacrifice! But it’s more comfortable just to think of it as temple monkeys.

I have gone paid. Now is a great time to subscribe and support my writing. It costs just £3.50/month, and yearly subscribers get a great big 40% discount, plus a free copy of my book:

And occasional reader. Sorry.

Great writing

Jeez, wow. I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t be able to stay psychologically healthy in proximity to that situation — can I ask, what causes you to stay in the area? (Is there good to balance out the bad?)