Apologies for the hiatus. I was away and then ill. I’m going to try and write more to make up.

I feel compelled to react to the political events of the last few days, which are the worst and most shameful I have ever experienced.

I try not to write as a partisan. I hate the knee-jerk anti-Americanism of many Europeans who should know better. But sometimes moral clarity is more important than clever analysis.

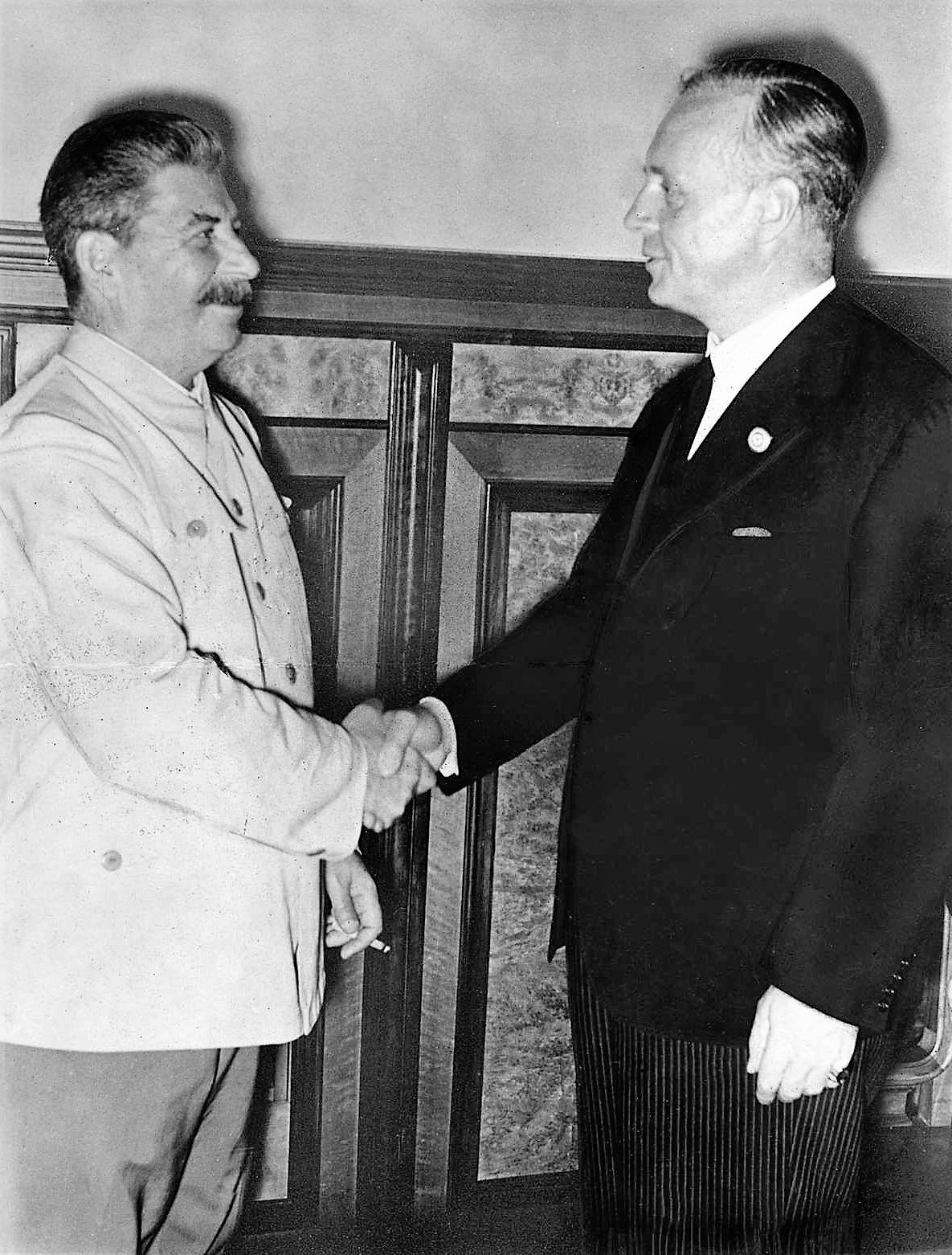

I never thought I would see the day that the US would vote in the United Nations besides Russia and North Korea, against a free country fighting for its survival.

I never thought I would see the US negotiating over that country’s future, over its head, with its invader.

I never thought I would see the US openly browbeat and bully weaker countries who are, or thought they were, its allies.

This is all utterly disgusting and disgraceful.

Authoritarianism and chaos

Nevertheless, let’s turn to analysis.

Looking back at the series of articles I wrote on democracy at the turn of last year, obviously in a broad sense I feel vindicated:

The global defeat of democracy: a scenario

(This is the first part of a larger essay developing my thinking on international politics today. The whole piece should serve as a backdrop to some more specific ideas on culture that I hope to work out next year. I’ve written other newsletters on democracy:

Democracy has never seemed so at risk or authoritarianism so rampant. When I wrote the above, it felt a little controversial. Now these worries are mainstream.

Getting into the details, though, I missed some of the subtle links between democratic failure and authoritarianism. I wrote that democracies had problems with sclerosis and with debt:

But my main worry was that these problems would weaken democracies in the international competition against authoritarians. What I hadn’t anticipated was how they might play into renewed authoritarianism within democratic systems themselves.

In particular, the Trump-Musk axis in the US is using the unsustainable US deficit as a reason to cut spending. Now, Elon Musk is a talented manager and he may succeed in increasing the efficiency of the sprawling US bureaucracy. It is much less likely that he’ll sustainably cut the gap between spending and taxation, because the biggest sources of spending are out of bounds, and besides, Trump is planning large tax cuts. But taking an axe to bureaucracy has another effect: it intimidates anyone who might consider resisting you. And for the new authoritarians, that’s not a bug but a feature.

On the other hand, Trump’s tax cuts and tariffs, plus his pressure on the Fed to keep interest rates low, are likely to lead to inflation. That’s another solution to unsustainable spending! You have a soft default and pay back your debts with devalued money. But it has a cost. Money, as economic theorists like to say, is memory; it’s a record of how society doled out rewards in the past, a pillar of the social system. Instability in money is socially destabilizing. Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday described how the interwar hyperinflation in Austria destroyed the bourgeoisie and led towards authoritarianism. (The 1960s and 1970s, whose less extreme levels of inflation are probably more relevant today, were also times of social chaos.) This isn’t necessarily a deliberate choice by Trump, but it is a likely consequence of his actions.

The other Thucydides trap

Turning to the international side of things: I belong to a little political economy reading group, and the other day we read Thucydides.

I never had much time for the idea of the “Thucydides trap”, that China would be forced into conflict with the US because its time was running out:

It seems much more like the opposite to me: China is strong and growing, it’s at the centre of Asia i.e. the centre of the future world, it has demographic problems but they won’t hit for a while, and anyway so does everybody else. And indeed, though China is sabre-rattling round Taiwan, it is the US that has been the economic “aggressor”, putting up tariffs and trying to prevent advanced chips from entering the country. China has chilled, built alliances and continued to grow, behaving more like a hegemon-in-waiting than an insecure power.

But there’s also a different lesson in Thucydides. One side in the Peloponnesian war, Athens, is an internally democratic nation. They are self-conscious and proud about this. Their leader Pericles describes their commitment to individual freedom, and go-ahead mindset, in his famous funeral oration:

Our constitution is called a democracy because power is in the hands not of a minority but of the whole people. When it is a question of settling private disputes, everyone is equal before the law…. And, just as our political life is free and open, so is our day-to-day life in our relations with each other…. When we do kindnesses to others, we do not do them out of any calculations of profit or loss: we do them without afterthought, relying on our free liberality. Taking everything together then, I declare that our city is an education to Greece…. In her case, and in her case alone… no subject can complain of being governed by people unfit for their responsibilities…. What I would prefer is that you should fix your eyes every day on the greatness of Athens as she really is, and should fall in love with her. [my italics]

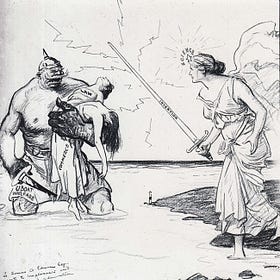

Athens starts off with huge prestige, as the leader of a league of allies which has defeated the Persian empire. But gradually, in the years before the war, this alliance is converted into an empire:

The leadership of the Athenians began with allies who were originally independent states and reached their decision in general congress….

After this Naxos left the League and the Athenians made war on the place. After a siege Naxos was forced back to allegiance. This was the first case when the original constitution of the League was broken and an allied city lost its independence….

As a result, unsurprisingly, “the Athenians as rulers were no longer popular as they used to be”. Eventually Sparta — a brutal slave state, which Thucydides records as committing deliberate mass killings of its Helots — leads a revolt.

As the war progresses, the quality of Athenian leadership declines from the wise Pericles to the demagogue Cleon, a populist who believes “states are better governed by the man in the street than by intellectuals”. Cleon has a kind of ruthless, realist clarity. Supporting the decision to kill the entire male population of Mytilene, a revolted ally, he says:

What you do not realize is that your empire is a tyranny exercised over subjects who do not like it and who are always plotting against you; you will not make them obey you by injuring your own interests in order to do them a favour; your leadership depends on superior strength and not on any goodwill of theirs…. it is a general rule of human nature that people despise those who treat them well and look up to those who make no concessions.

And, at the Athenian high point of the war, he prevents peace by making maximalist demands.

In short, Thucydides’ Athens is a proud, “liberal” imperialist that fails to realise how it is making itself hated. It starts by thinking of itself as an “education to Greece”, alienates its former allies by bullying and short-run self-interest, and is eventually defeated by an alliance led by Sparta, a state which is internally far less democratic, but which can nevertheless rally resistance.

This seems like a relevant lesson, in a week when America has burned soft power in extraordinary speed and quantity.

The aftermath of the Athenians’ disastrous defeat in Sicily, by the way, is as frightful as anything from modern warfare.

Those [Athenian prisoners] who were in the stone quarries were treated badly by the Syracusans at first. There were many of them, and they were crowded together in a narrow pit, where, since there was no roof over their heads, they suffered first from the heat of the sun and the closeness of the air; and then, in contrast, came on the cold autumnal nights, and the change in temperature brought disease among them. Lack of space made it necessary for them to do everything on the same spot; and besides there were the bodies all heaped together on top of one another of those who had died from their wounds or from the change of temperature or other such causes, so that the smell was insupportable. At the same time they suffered from hunger and from thirst. During eight months the daily allowance for each man was half a pint of water and a pint of corn. In fact they suffered everything which one could imagine might be suffered by men imprisoned in such a place. For about ten weeks they lived like this all together; then, with the exception of the Athenians and any Greeks from Italy or Sicily who had joined the expedition, the rest were sold as slaves. It is hard to give the exact figure, but the whole number of prisoners must have been at least 7,000.

Translations from the Penguin edition by Rex Warner.

If you think this is interesting, why not become a paid subscriber? About half my posts are paid or partly paid. A subscription costs just £3.50/month, and yearly subscribers get a great big 40% discount, plus a free copy of my book.

I questions that the debt/deficit had any major impact on the ability for Trump and Musk to exert power. Elephant in the brain/ tail wagging dog. Just like slapfight with Zelenskyy actually postdated the commitment to cut military aid to them.