The global defeat of democracy: financial weaknesses

Bright pink mountain? What bright pink mountain?

Here at last is the third in a series of articles laying out the pessimistic case for democracy’s future. Their aim is not to spread alarm and despondency, but to encourage a bit of forethought.

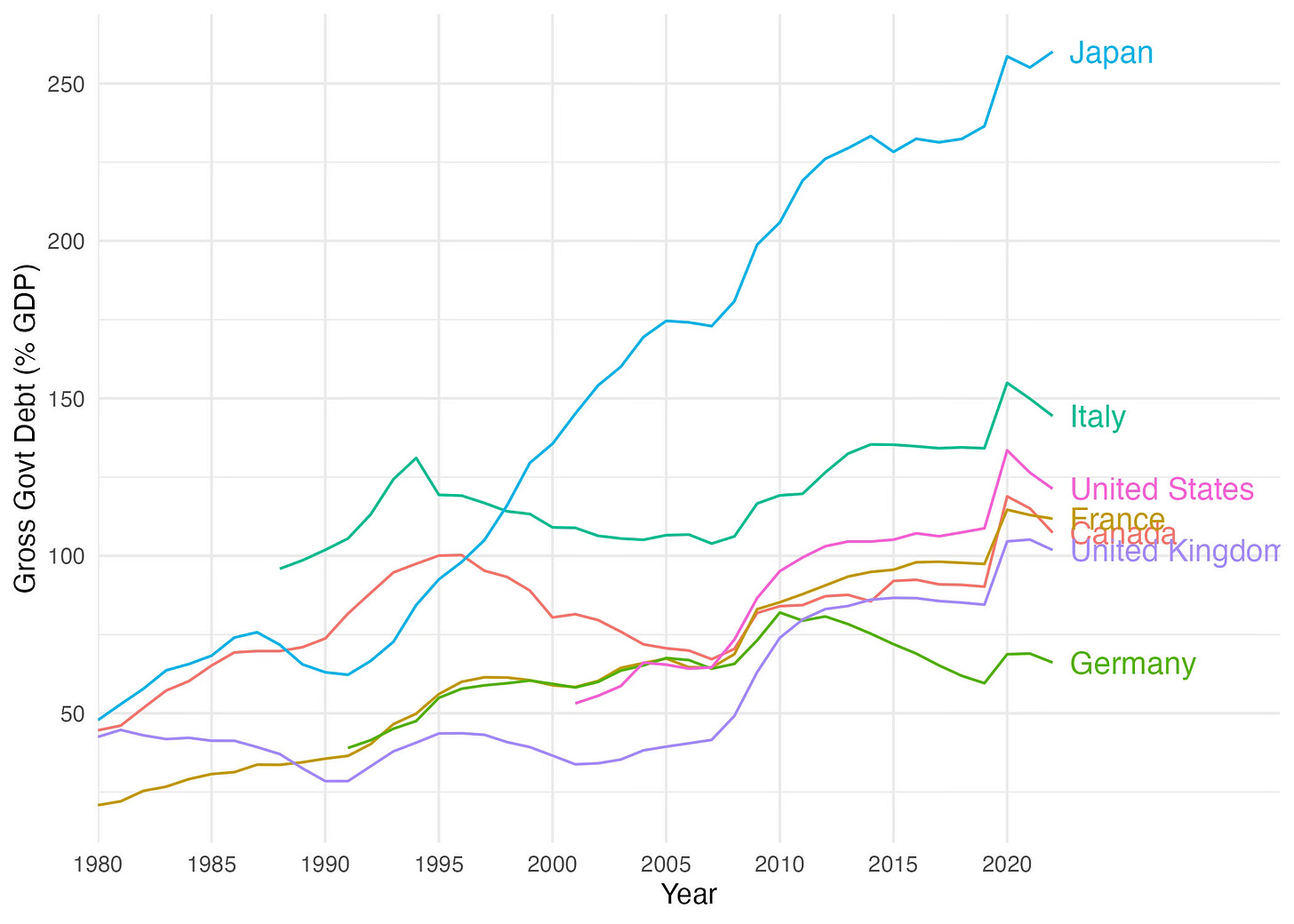

Let’s talk macro. Here is government debt for the G7:

Here’s the long run picture for the UK:

If you went back to the 19th century, you’d find an even higher peak for the Napoleonic wars, followed by a long decline.

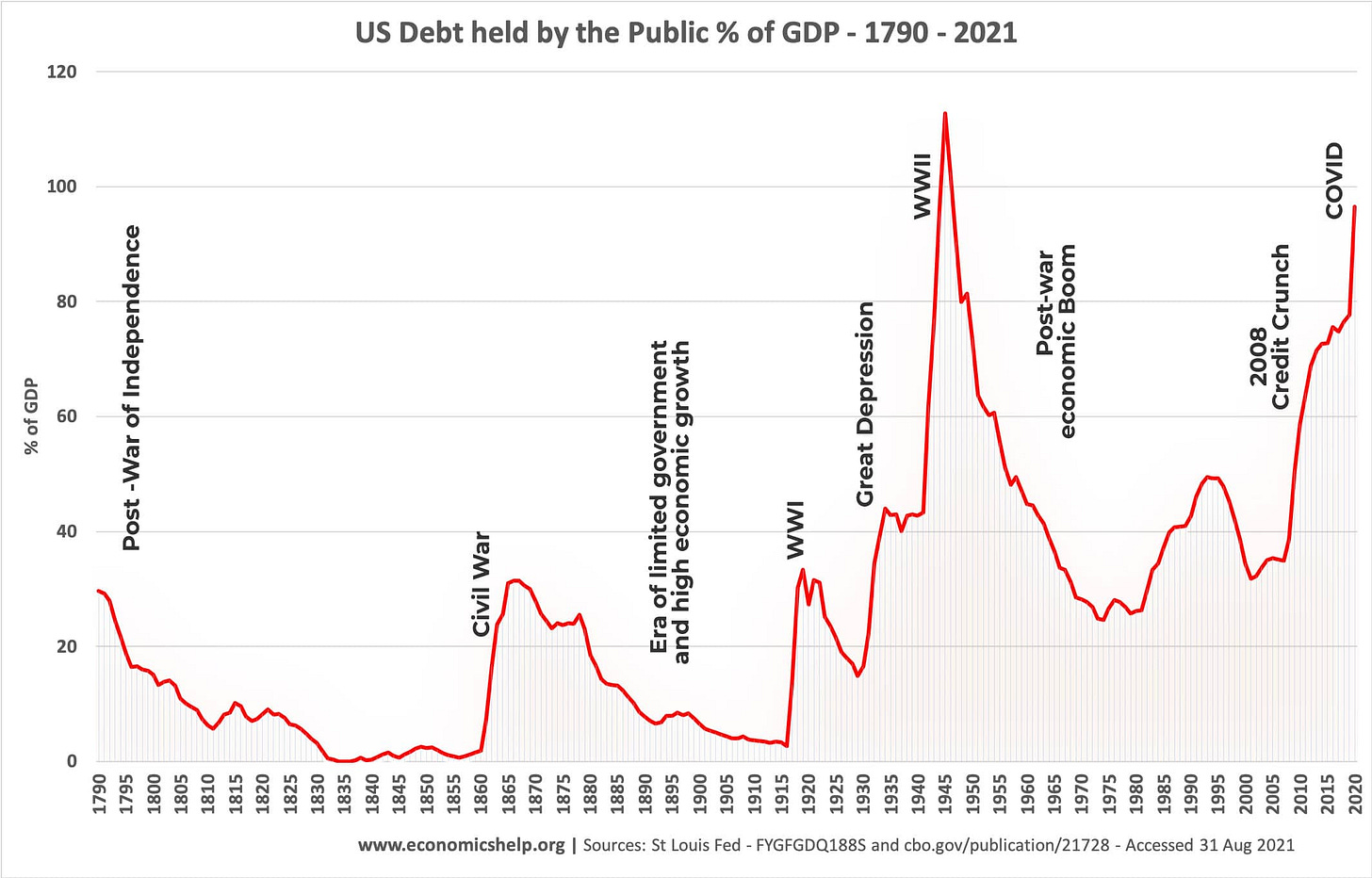

And for the US:

These look like large numbers! Before now, the UK only had so much debt after global wars. The US has incurred as much debt responding to 2008 and COVID as it did to fight World War II. 2008 and COVID were big events, but not that big.

There is no mechanical way to tell how much debt is sustainable. The world’s most indebted government is Venezuela, a basket-case; the second most indebted is Japan. Japan seems fine at 270% of GDP. Ukraine defaulted in 2015 at 80%. The countries with low government debt include plenty of deplorables: Afghanistan, the DRC, Bulgaria…. The key questions are, do governments have the will and capacity to pay, and do creditors believe so? If they do, they will be willing to roll over present debt.

The figures above aren’t the whole story, because they don’t include the large unfunded liabilities generated by welfare states. Social security and medicare in the US, the state pension and NHS in the UK, and their analogues elsewhere, are not embodied in IOUs, but they involve commitments, with varying degrees of explicitness, that a democratic government would find very hard to break.

Government bodies tasked with monitoring the long-run sustainability of public finances have to take this into account. Here is the UK Office for Budget Responsibility:

… debt begins to rise again as a share of GDP from the mid-2030s as age-related spending pressures kick in and interest costs rise. Debt passes 100 per cent of GDP again in the mid-2040s and then rises exponentially to 310 per cent of GDP by 2072-73....

If a government wanted instead to keep debt from rising above 100 per cent of GDP over the long term, this would require a permanent increase in taxes and/or cut in spending of 4.4 per cent of GDP in 2028-29. There is also an alternative, and arguably more realistic, adjustment that estimates the staggered improvement in the primary balance in each decade to reach this level of debt. We estimate this to be a 1.5 per cent of GDP adjustment made to the primary balance every decade.

If numbers lose you, take my word that a government does not simply cut spending by 4.4 per cent of GDP. Similarly, here’s a nice graph from the US Congressional Budget Office:

Why do developed democracies incur large debts? Governments are tempted to soak the future to pay for the present, because rationally ignorant voters can’t tell whether budgets are sustainable or not. That is conventional wisdom among economists and it has not been much challenged since the theory was put forward in the 1980s. I’d add that voters will never choose to believe a spending level is unsustainable if it benefits them, or makes them feel morally virtuous.

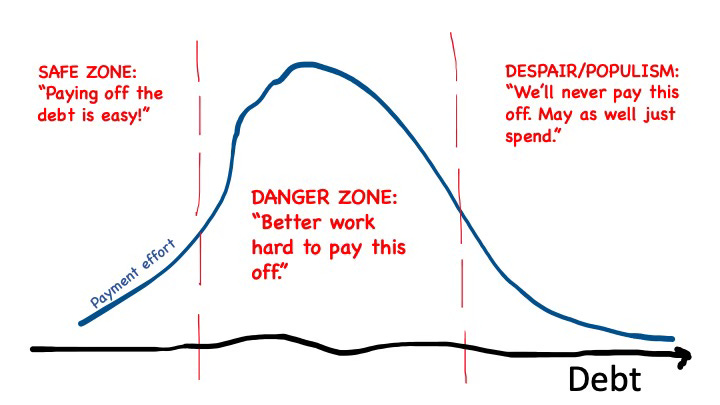

Practical judgments of long-run debt sustainability depend on the government’s reaction to increasing debt. Ideally, as it goes up, they should put the brakes on. In fact, empirical observers find that this happens up to a certain point. Beyond that point, more debt does not make governments work harder to pay it down. It is not hard to think of a theory to fit this data. It is the same theory that explains why individual debtors are sometimes found drowning their sorrows in bars. Here’s a picture:

Policy-makers have not just let debt get high, they also seem more ready to respond to crises by turning on the spigots. I already mentioned COVID. The Bank of England also turned on the Quantitative Easing taps after Brexit. As the OBR puts it, a little drily, the frequency of crises seems to be increasing.

The despair/populism zone sets debt up as what Douglas Adams called a Somebody Else’s Problem.

The Somebody Else’s Problem field... relies on people’s natural predisposition not to see anything they don’t want to, weren’t expecting, or can’t explain. If Effrafax had painted the mountain pink and erected a cheap and simple Somebody Else’s Problem field on it, then people would have walked past the mountain, round it, even over it, and simply never have noticed that the thing was there.

Somebody Else’s Problems generate unexpected surprises — “unexpected” in the sense that people have buried their heads in the sand. Explicit default is one alternative. Another is that governments burn away their debt using financial repression and, again, “unexpected” inflation. Financial repression means making your citizens lend to you at low rates. For example, prudential rules may force pension funds to invest in government bonds. This is what happened after World War Two: the US shrunk its debt by keeping nominal interest rates below GDP growth and by bursts of inflation. (See this paper.)

Default threatens political systems. Government debt involves three, possibly overlapping actors: the government, creditors, and citizens. The government promises the creditors that it can make its citizens pay the interest on its debts. Dictators might find this easier: they don’t face losing elections if they squeeze their subject population. (This is one reason why lending to dictators is ethically questionable.) But creditors also have to believe that the government itself will be willing to repay. Especially when debt is domestically held, democracy might have an advantage here. In general, bankruptcy is likely to make creditors, whether external or internal, willing to contemplate regime change. They may also have leverage to do it. Louis XVI called the Estates General to raise new taxes. The rest is history.

Sidebar! I’m currently a bit obsessed with the Italian city-states, so I couldn’t resist looking up how they performed with regard to government debt, which they basically invented (thanks, you bastards). Here is a cool picture from David Stasavage:

It shows how city-states started issuing debt well before territorial states (mostly princedoms). They got better at it over time, with interest rates getting lower. But when princes got in on the act they caught up. Stasavage reckons that the city-states preserved an interest rate advantage, presumably due to more credible institutions ensuring repayment. But he also points out that the popular discontent and revolutions of the 15th century often led to higher interest rates, because they reduced the power of a city-state’s domestic creditors. The 15th century had its populists too: since they didn’t have fiat currency, they had to take more direct action than simply printing banknotes. One approach was “just burn the IOUs”.

But the most direct threat to democracy from fiscal weakness is the international context, because conflict requires credit.

People think wars are won by the country with most resources. Nope: wars are won by the country that can marshal the most resources. Not the same thing. It is a matter of will as well as raw capability. Britain had, by some estimates, a ten times smaller economy than France under Louis XIV, its rival at the turn of the 18th century. But France’s creditors had been burned too many times before. Britain gained credibility — credit in the most literal sense — by developing institutions which guaranteed payback. It could raise the money to win. Similarly, the Netherlands beat Spain in the seventeenth century struggle for hegemony because they had better credit institutions.

War drives debt sky-high, and even the winners carry a burden. They often respond by retrenching, which encourages new challengers. Britain and France did so after the Great War. The West did it after defeating the USSR in the Cold War (by outspending it in an arms race). We have cut our military budgets back and now been caught short with rusting navies and not enough shells. What is more worrying is that, at the start of a potential conflict, we have the levels of debt you would expect at the end of one.

This is not just a hypothetical problem which will be realized if the new cold war becomes hot. Credit not only determines nations’ ability to fight wars, it constrains their choices to fight in the first place. Famously, Britain was forced to abandon its expedition to Suez in 1956 after a run on the pound, when the US refused to help it out. It is less well known that in 1936, France was partly deterred from stopping Nazi Germany’s remilitarization of the Rhineland by the threat of capital flight. This is when Hitler supposedly remarked: ““[i]f France had marched into the Rhineland. . . we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs.” It is hair-raising to contemplate that the horror of the Second World War might have been stopped if the Third Republic had had more solid financial backing. And today we are struggling to fund Ukraine.

In the context of high politics, it matters who owns the debt. Behind the technicalities of public finance lies the exercise of collective will. Japan’s high public debt might seem like a tempting target to bet against. In fact, that trade is known as the “widowmaker”. One plausible reason is that the Japanese public and institutions have high trust in their government’s willingness to repay. In World War One, US financiers raising war loans could answer doubts about the 3½% interest rate as follows: “Anybody who declines to subscribe for that reason, knock him down.”

Rationalist theories of war pose a puzzle: if two nations both correctly estimate their chances of winning a war, why would they fight, when they could negotiate on that basis instead? One answer, I think, is that war-fighting is an act of collective will. Citizens will be prepared to make sacrifices so long as they believe others will too; this means there are multiple equilibrium levels of fighting effort, which makes war indeed unpredictable and lets equally rational actors have different expectations. Credit is one part of this picture, and credit too is subject to multiple equilibria. (If you expect the government to default, you will demand higher interest rates, which in turn makes default, and losing wars, more likely.) One question about the future is: how ready will domestic creditors be to support different levels of international assertiveness by their governments? Partly this is a question of institutional arrangements, but it is also partly a question of what populations will support. So, the financial weaknesses in this post are linked to the political weaknesses described in my last post: atomized peoples with no strong shared world view and chronically low trust in their leaders.

The global defeat of democracy: political weaknesses

This is part 2 of an extended essay about democracy in 2023, laying out the pessimistic case. Part 1 is here. There is no will of the people. Individuals have political needs, like freedom, prosperity and security, but no political will, because in general

At the same time, there are important uncertainties about how national willingness-to-pay might react to future conflicts. Everyone remembers that in the 1930s the Oxford Union voted “this house would not fight for King and Country”, but they did in the end. More recently, Ukraine found surprising unity and strength when it was attacked.

Foreign creditors may also have their own views. 15 per cent of US government debt today is held by Chinese owners, including 5 per cent held by the Chinese central bank. If you are feeling triumphalist you can think of this as a show of support for the West’s solid financial institutions. But another reason to extend credit is why the merchant Lheureux lent to Madame Bovary: because credit is power. (In 2016 the US Center for Strategic and International Studies had a more optimistic take. I think their argument assumes that peacetime logic will keep holding in times of conflict. Still, it’s true that the proportion of debt held by China has fallen over the past decade.)

So, our financial weakness has three risks. First, if the current conflict gets hotter, Western countries may not have the financial headroom to win. Second, even if it doesn’t, the West and in particular the US may simply give up hegemony without a fight. (It’s interesting that so far, the US response to a serious threat to world trade from the Houthis and Iran has been… pretty tepid.) Arguably, in the context of large scale modern war, it is better to surrender than to fight and lose. But that is too simple, because surrender in a negotiation always tempts the winner to demand still more. The third and most serious risk, then, is that present weakness may lead us to face truly existential challenges in future.

What is to be done about this? Well, as an individual, think about inflation-proofing. Central bank quantitative easing, the innovation of the 2010s, is a form of financial repression where the bank prints money and buys government debt, keeping it expensive and yields and interest rates low while pushing cash into the economy. In theory inflation is “sterilized” because the bank will later perform quantitative tightening, selling the bonds back and taking cash back out of the economy. For sure it will! Unless there’s another crisis.

What to do collectively is harder to know. After all, the usual way “we” act collectively is via democratic elections. But I have been talking about financial weakness as a predictable pathology of just those elections. Long-run solutions to these problems, like all the problems this series has discussed, lie not really at policy level but at institutional level. So we’ll postpone this question for now. Next, we’ll focus directly on the geopolitical context, which has been in the background of all the posts so far.

Some papers I read while writing this:

Debrun, X., Ostry, J.D., Willems, T. and Wyplosz, C., 2019. Debt sustainability. Sovereign debt: A guide for economists and practitioners, 151.

Rasler, K.A. and Thompson, W.R., 1983. Global wars, public debts, and the long cycle. World Politics, 35(4), pp. 489-516.

Shea, P.E. and Poast, P., 2018. War and default. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(9), pp. 1876-1904.

Stasavage, D., 2016. What we can learn from the early history of sovereign debt. Explorations in Economic History, 59, pp.1-16.

If you enjoyed this, you might like my book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present. It’s available from Amazon, and you can read more about it here.

I also write Lapwing, a more intimate newsletter about my family history.

Great piece