One function of social science is to sell cope: to tell societies what they want to hear on challenging topics. I wish it weren’t so, but it is just a response to demand, in a market where the truth has no immediate payoff.

Once, women had more children than they wanted. Many women died in childbirth, and children often died young too. Over time the birth rate came down, first in Europe and then elsewhere as societies developed. But it did not stop coming down when women had as many children as they wanted. Instead, now in most advanced societies they have fewer children than they want, and fewer than the replacement rate, so the native-born population is shrinking.

This is worrying. First, it could lead those societies essentially to die out, which would be bad, just as any civilization dying out is bad. Second, it causes economic problems because there won’t be enough workers to take care of the old people; perhaps these problems can be solved by immigration, but that might bring problems of its own, and it seems like a temporary sticking plaster. Last, and most important of all, low fertility involves a lot of individual suffering, because many people who don’t have children are sad about that.

(By the way, throughout I’m using “fertility” in the demographer’s sense of how many children people actually have, not in the medical sense of the biological capability to having children.)

The modern decline in childbirth coincided with changes in divorce law, the rise of welfare states, new contraceptive technology including the pill, the entry of women into labour markets and the rise of feminism. You might think that some of these social changes were linked to the decline in childbirth. If you believe these changes are good, that would be uncomfortable for you! You might worry that they are not unalloyed goods, and at least, you might have to think about that.

Gender equity theory offers a different explanation for fertility. It says that while fertility has declined due to feminism and women working, it only reaches very low levels because society is not feminist enough! In other words, there is a U shaped relationship between society and the level of gender equity. At first, with increasing gender equity, fertility declines. Later on, as gender equity increases more, fertility rises again.

In short, to those who fear that Western societies have dug themselves a hole, gender equity theory says “keep digging!” The optimism of this view makes me wonder if gender equity theory is a cope.

It’s an interesting theory, anyway, so let’s look at it. (The original paper introducing it is McDonald 2000; he wrote a follow-up in 2013.) The story is that society gets more gender-equitable in two phases. In phase one, labour markets open up. Women can get a wider range of jobs, and they face less discrimination in their careers. They might like to combine a career and family. Unfortunately, family institutions are still quite sexist, and they are expected to do most of the childcare. As a result, many women pick a job over a family. This is when you get what the demographers call “lowest low fertility”, usually defined as a total fertility rate (TFR) of 1.3 or less.

In phase two, the family becomes more egalitarian. Men get their act together and start to do their share of washing up and changing nappies. Society might also change to make employment more family-friendly, for example by providing crèches. As a result, women find it easier to combine motherhood and work, and fertility rises again. The utopia is that when this process is complete, most couples will be able to have the number of children they prefer. Meanwhile, societies are on the upward-sloping part of the equality-fertility curve. More equal societies now have higher fertility.

The evidence

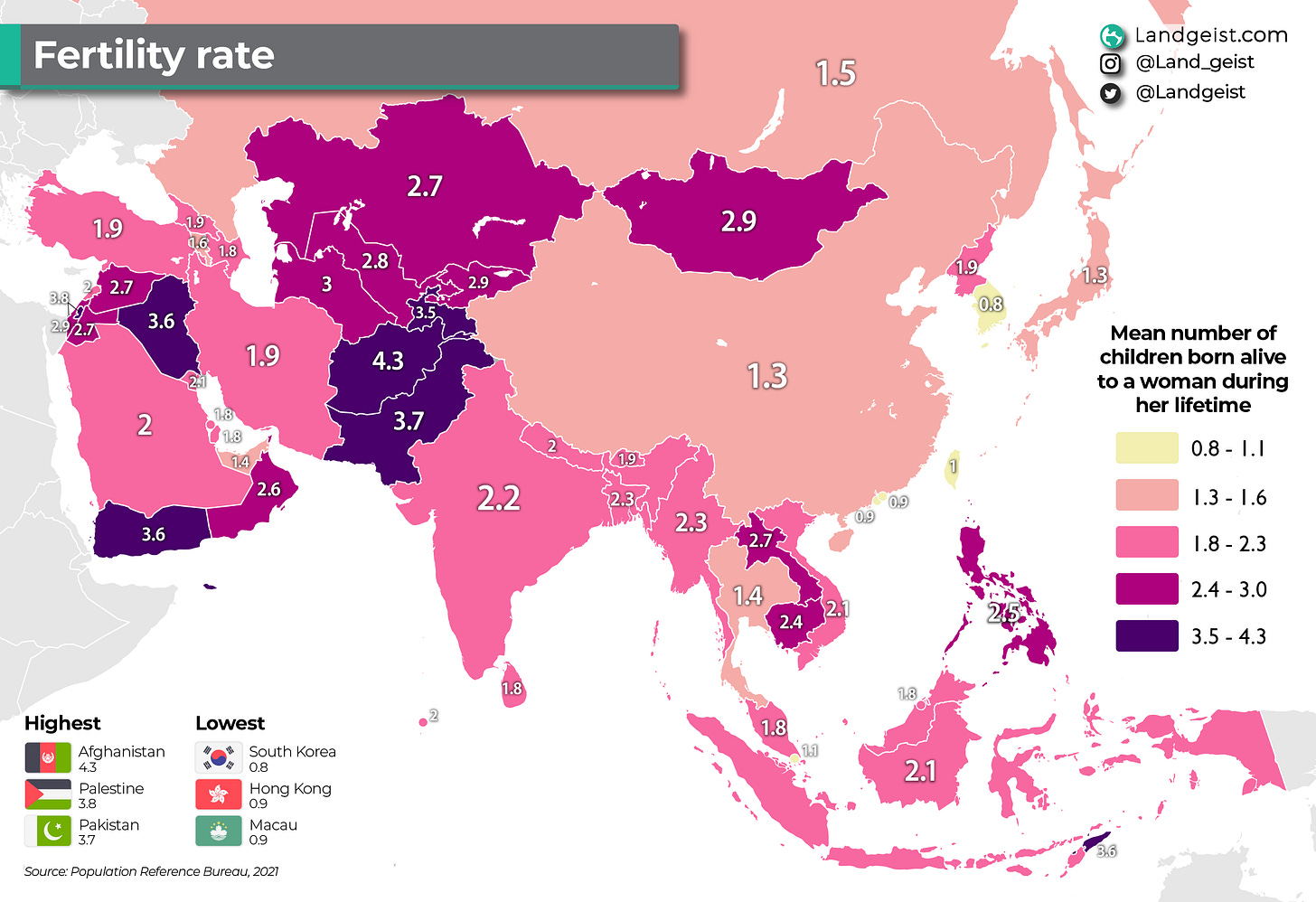

The key exhibit to support this theory is cross-country differences in fertility, in particular between northern and southern Europe, and Europe and East Asia. Against the old stereotype (and previous reality), fertility is now higher in northern Europe than in the mostly Catholic south.

One interpretation is that in the south, family expectations are still quite sexist. By contrast, progressive Sweden and Denmark have relatively high TFR, perhaps because they have more egalitarian families.

East Asian fertility goes even lower, to below 1 in South Korea, Taiwan and some other places along the Chinese border, and to lowest-low levels in Japan and China. Again, gender equity theory seems like a good explanation for this, if East Asian countries have rather hard-set expectations about family gender roles.

This chart from Doepke et al. 2022 looks at the cross-country evidence in a slightly more “principled” way. OECD countries where many women have jobs used to have lower fertility. Now that relationship has reversed, and those countries have higher fertility.

The cross-country differences are the strongest piece of evidence for gender equity theory, and the most interesting, because they show that the theory could explain an important part of worldwide variation in fertility.

Other evidence

But as we know, cross-country evidence has limits. The southern Europe family probably is more traditionalist than the Scandinavian model, but many other things differ between those countries, and any of them might be an alternative explanation — the mix of immigrants, say, or the rate of economic growth.

So, what other evidence is there to support the theory? Well, some. For example, it turns out that fertility within couples depends strongly on whether both partners agree on having a child. That’s compatible with the idea that a “fair” division of labour in the family might increase the TFR. But note, it’s also compatible with any theory in which most children are not conceived via coercion. Does agreement of both partners depend on a fair division of labour? Well, again, the evidence for that is at cross-country level. Here’s an interesting graph from the source paper:

The x axis shows two measures of “fair family institutions” — one is how much childcare men do, one is how able women with young children are to work. The y axis is a bit complex: it shows, deep breath, the proportion of couples where the man wants another child but the woman doesn’t, minus the proportion of couples where the woman wants another child and the man doesn’t. The idea is that if these two numbers are very unbalanced, then there are structural factors making women less willing to have a baby. And this disagreement predicts overall fertility, because babies mostly don’t get made except by both parties’ agreement.

So this is interesting, but again we are back in cross-country world. A short summary of the evidence would be “couples only have a kid if they both want to; this happens more in Norway or France than Russia or Lithuania; one interpretation is that this is due to equitable family arrangements”. Could there be other causes? Sure. For instance, divorce rates are also notably high in many Eastern European countries:

The best micro-level evidence for gender equity theory comes from the easiest kind of gender equity to measure: state policies. There’s some evidence that funding for childcare and parental leave might increase fertility — effect sizes seem to vary across different programs. Again, I’m leaning on Doepke et al. here. There’s a certain number of unusual “nonlinearities”, “interactions” etc. in the studies they cite, which might suggest researchers are hunting for a significant effect, but eh, fine.

And that’s… about it? I have not found any really direct attempts to test the theory at the level of individual households, which is the obvious way to conduct a rigorous test. In their literature review, Mills et al. (2011) talk about “mixed results” examining the impact of egalitarian gender roles on fertility. So we’re left with some uncontrolled cross-country comparisons.

Dogs that don’t bark

Also interesting is the evidence we don’t see. For example, if I wanted to test gender equity theory, I’d naturally think of ethnic or religious minorities. Different religions and cultures might have different norms and expectations around the family, while sharing access to the same national labour markets. So we’d expect to see the lowest fertility among ethnic minorities with traditional family gender roles, in advanced countries with equitable labour markets.

That prediction does not seem to hold up in the UK:

Now one possibility is that migrants from e.g. Bangladesh not only have traditional family norms, they also have very limited access to UK labour markets. For example, perhaps women migrating from there often don’t speak English and so find it hard to seek work, though it’s harder to credit that for descendants of immigrants. Or maybe some ethnic minorities have strong beliefs against women working in the labour market — so in effect, for them, labour markets are not equitable, and they are on the early, downward-sloping part of the equity-fertility curve. That’s a somewhat ad hoc modification to the theory, because it turns the labour market into something that varies per culture, but indeed UK minorities with high fertility also have low female employment:

The theory has a similar problem with religious denominations in the US.

Mormons are interesting, because historically Mormon leaders discouraged married women from working; at the same time, on average, Mormon women worked at the same rate as other women in the US, with unmarried women working more and married ones working less. According to gender equity theory, Mormons should have low fertility: labour markets don’t discriminate against Mormon women, but family attitudes are highly traditional. That story very much does not check out. It also seems unlikely that evangelical Protestants or Catholics face less gender-equitable labour markets in the US than atheists or agnostics.

Sizing the effect

If we sum all this up, it seems as if there might be something to gender equity theory, but not as much as its proponents hope. It’s probably true that state support for childcare can increase fertility. And the differences between northern and southern Europe suggest that it is at least possible to combine female employment and higher fertility.

At the same time, this is far from a complete story. In particular it doesn’t mention some well-attested policies that do affect fertility. There is good evidence from cross-country studies, and cross-state studies in the US, that easy unilateral divorce lowers fertility. (This evidence is better than the simple cross-country differences described above, because it typically looks at changes in divorce law over time within a country, and how these impact changes in fertility — in technical terms, it uses difference-in-differences. That controls for many other differences between the countries in question.) The reason unilateral divorce might lower fertility is quite obvious: if your partner can walk out at any time with few penalties, it becomes risky to commit to having a child. Since most children end up with their mother after divorce, you could think of this as another example of gender-inequitable family institutions. But the dominant interpretation is that divorce law reform was a modernizing step.

There’s also good evidence that state pension provision lowers fertility. Again, the logic is simple: if the state promises to look after your old age, you don’t need children for that purpose. These effects seem as big and important as whatever is captured by gender equity (divorce laws decrease TFR by about 0.2, spending 10% of GNP on pensions decreases TFR by 0.7-1.6).

In fact, the most important point against gender equity is the effect sizes. Look again at that map of Europe. The southern countries have fertility of around 1.3. But the highly egalitarian countries mostly score around 1.7, about 20% below replacement fertility. Even France, the most fertile country, is well below replacement. If replacement fertility is a reasonable benchmark, then these countries are still far from reaching it. They are shrinking at 20% per generation instead of 40%.

Now for a contrast, look at the numbers in that barchart for religions. American Evangelicals and Catholics have a TFR well above replacement. Mormons are at 3.4, growing lickety-split.I am not holding this up as an ideal — no group needs to aspire to take over the planet — but if I wanted to understand how to get above replacement fertility, I would be looking at these guys, not Sweden. (The very good Shall The Religious Inherit The Earth talks about more of these high fertility “endogenous growth religions”.)

There is a character in The Big Short who decides to trade (supposedly) high quality mortgage-backed securities against low quality mortgage-sacked securities. He’s realized that the low quality mortgages are garbage. But he thinks the high quality ones are safe! He hasn’t yet understood: they’re all garbage.

I’m interested by people’s tendency, when they realize something is wrong, to clutch at this kind of straw. As I’ve written before, it’s like a cruise ship sinking: one end is sliding into the water, and the passengers at the other end are pointing down the deck: “Boy, those guys are in real trouble!”

I think gender equity theory might be like this. Our societies and cultures seem to be failing a rather basic survival test. This is hard to deal with. Gender equity theory lets us comfort ourselves by saying “well, some places are failing worse!” Sure. South Korea will be irrelevant in a generation. In Sweden, it’ll take two or three.

Further reading

All the above should come with caveats. This is just one non-specialist’s take. Societies are always worrying about their demographics, and the worries often swiftly change direction. In the 18th century, Oliver Goldsmith writes The Deserted Village while behind his back Britain’s population is booming. Then with Malthus we get the first worries about population explosion. Twenty years ago we were still worried about the “population bomb”; now it’s the opposite. A lot of this is linear extrapolation from existing trends — even sophisticated statistical work is usually like that under the hood — and as such, it can’t really account for the fact that humans creatively respond, both individually and collectively, to the problems they face. Maybe in fifty years, we will have figured out a new egalitarian family settlement, populations will have stabilized, and we’ll look back calmly at today’s panic.

To which my only response is: sure, but hope is not a strategy!

The literature on fertility is huge, and spans demography, economics and sociology. The recent Doepke paper mentions a lot of literature, and this slightly older literature review is also useful. There are other theories than gender equity theory. In particular Van de Kaa, who coined the phrase “second demographic transition”, claims that individualism, or hyper-individualism, is the long run cause of very low fertility. Another interesting theory claims that social norms, spread by late-twentieth-century demographers concerned about population explosion, led to a policy-driven, simultaneous, sharp decline in fertility in much of the developing world.

If you enjoyed this, you might like my book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present. It’s available from Amazon, and you can read more about it here.

You can also subscribe to this newsletter (it’s free):

Kids are expensive. Actually birthing the child is expensive in many places, feeding and clothing (and diapering) is expensive, etc. At a certain point where having children is more of a choice (in the world of easy birth control, easy divorce, more gender equality in work, etc.), being able to pay for it is going to be a big part of the decision.

In particular, childcare is expensive. I wonder if there's any way to compare numbers on societal groups or countries or whatever where it's more or less common for a relative (eg grandmother) to look after kids so both parents can work (this might explain why descendants of some immigrant groups continue to have more kids).

So if I read this right, the explanations that have been proposed for the continuing decline of fertility are:

- the progressive package: divorce law, welfare states, contraception, working women, feminism. also: state pensions

- hyper-individualism (Van de Kaa)

- declining religiosity

- older fears of overpopulation

- gender equity theory, saying that it's the result of an mismatched partial transition to true gender equity

Is this an exhaustive list? I'm not super well read on social sciences, but I think I've seen other possible factors mentioned, that might also be relevant, such as:

- rising standards of living, which could be the underlying cause of both progressivism and individualism (in that we can now afford them), but also have direct effects on the family

- changes in domestic economy: kids used to be helping hands in a traditional farming or herding environment, now they're a net economic drain until the late teens at least; also as material things get cheaper, professional human attention gets comparativily more expensive, so the health care and education needed to raise a kid become larger as a share of family expenses

- a rising sense that civilization on Earth is globally threatened - by nukes since the mid 20th century, plus now by climate change and a whole assortment of eco crises - "is this the kind of word you'd want your kids to grow in"?

- possibly a feeling of saturation from high levels of interconnected population - a sense of overwhelming creative and economic competition of all-against-all

But if were to improvise a speculative narrative right here, I'd add: the traditional religious injunctions to breed and multiply *were themselves already a major cope*. Because the sex drive came much before, and in pre-modern times, that means lots of breeding. So it's more like giving a post-hoc blessing to something that was already happening, to nudge it in socially helpful directions maybe, but not to make it happen altogether.

The big change, to put in very general terms, is that we now have individual control. By an large, a kid happens only when both parents want it to. Ironically, now that we control the process, religious or cultural injunctions to breed can actually be effective, because there is more of a decision that can be influenced.

Finally, I don't give much credence to people saying "I'd prefer to have more children, but". I rather think people are basically expressing their preferences with their actions, but then projecting the reasons outward to because it feels more comfortable to do so.