Adam Smith’s second big idea

Liberalism is challenged by gains from scale

Apologies for my European-style long vacation (the younger generation are to blame). I’ll try to speed up my work rate, but I will always prefer quality to quantity.

Adam Smith’s famous big idea is the invisible hand: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” This has been the guiding light of neoliberal public policy for 40 years. Sometimes the government privatized companies to let them survive in the market, sometimes it stepped in to provide incentives where markets couldn’t.

But he had another big idea, almost as famous among economists, but perhaps less known among the public. He introduces it very early on in the Wealth of Nations:

To take an example, therefore, from a very trifling manufacture, but one in which the division of labour has been very often taken notice of, the trade of a pin-maker: a workman not educated to this business… could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. But in the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades. One man draws out the wire; another straights it; a third cuts it; a fourth points it; a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business; to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper…. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind…. Those ten persons… could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day.

Specialisation, in other words, produces massive efficiency gains. And what makes specialisation possible is market size:

When the market is very small, no person can have any encouragement to dedicate himself entirely to one employment…. It is impossible there should be such a trade as even that of a nailer in the remote and inland parts of the highlands of Scotland. Such a workman… will make three hundred thousand nails in the year. But in such a situation it would be impossible to dispose of one thousand, that is, of one day’s work in the year.

Today, once again, this second lesson is important. Computation is unlocking huge efficiency gains, which allow firms to have greater scale than ever before. But the benefits of this are limited by market size.

Europeans bewail their lack of tech unicorns. Entrepreneurs often blame Europe’s over-regulation. It is probably just as important that Europe is composed of different countries, all with their own legal and regulatory systems. No sane person would choose to start Amazon in Belgium. It just isn’t a big enough launchpad for a hyperscaler.

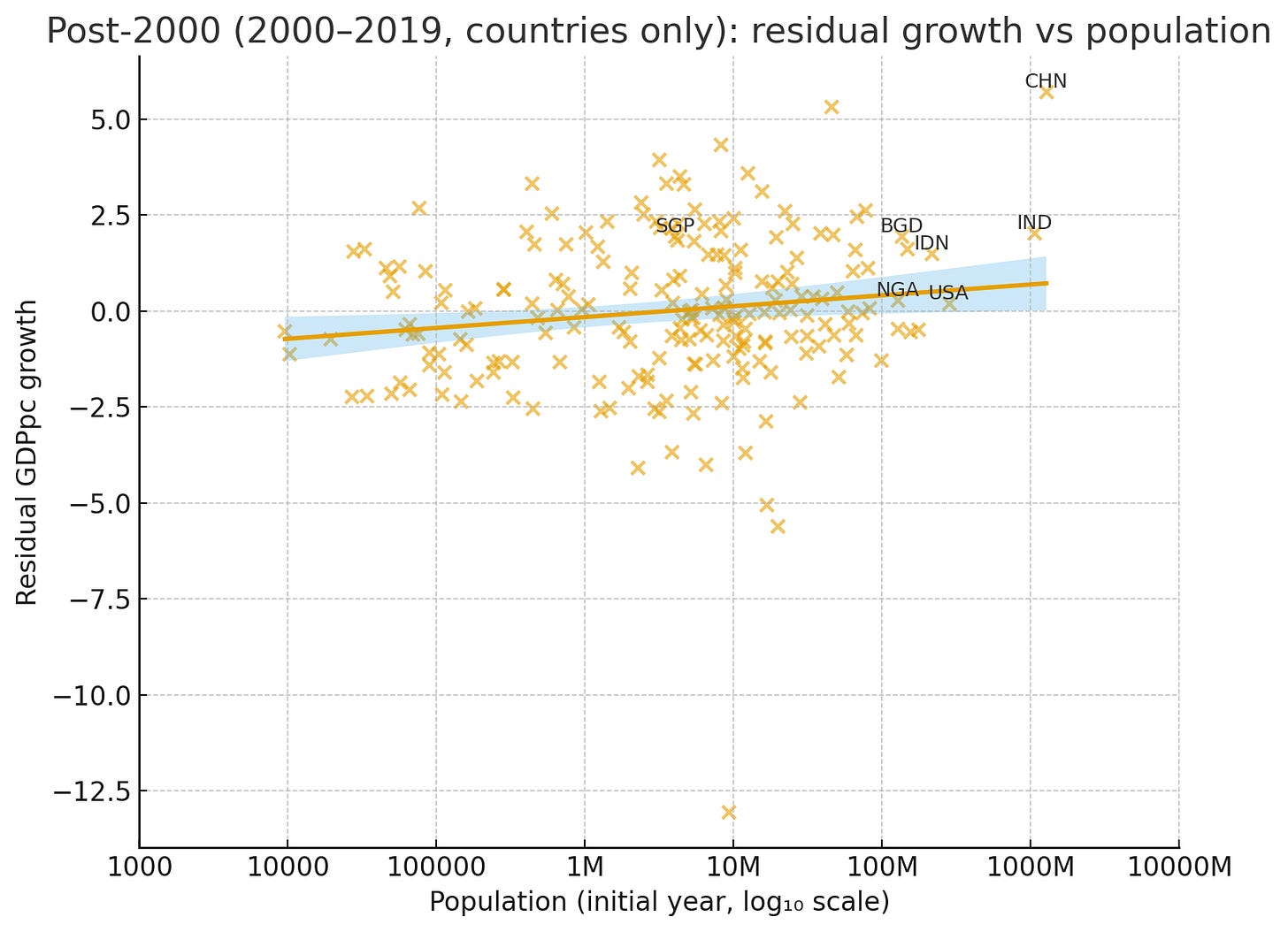

To back up my story here are some quick cross-country growth regressions (done by ChatGPT, so take with a pinch of salt — indeed, the first time I asked, ChatGPT simply made up the results 🙄 — I think now it has actually used the data. UPDATE: it used the data but included regions such as “world” and “East Asia” as countries. Grr. Redone.). They regress GDP growth on population for the years before and after 2000. The dependent variable is GDP growth. Before 2000, the effect of population is small and negative. Afterwards, it is positive and highly significant. The plots below show the regressions in scatterplot form.

One way to think about Trump’s tariffs is that he is forcibly creating a single market — America-centric, on America’s terms, and to the advantage of America, for sure. You can think of this as the political expression of technological change in the economic base. (A classic Marxist idea.) He is pushing America’s allies to truly open their markets. This is succeeding by brute force, where the more idealistic and conciliatory approach of previous transatlantic free traders failed.1 On this account, economists who lecture him on how tariffs are bad are missing the point.

At the same time, Trump’s approach is a tacit admission of American weakness. The US has moved from planning a trade framework for the entire world, to bullying the Europeans and Canadians.

Most of the world’s population lives in Asia. It is here that we will see the true effect of gains from scale. A trading system that includes China and India would have truly intimidating potential for scale. And indeed both these countries have their own, boisterous tech giants. It seems quite possible that China will be able to outbid the US’s offer to other Asian nations, and to weave itself into an Asia-centric trade network as the central node:

Trade wars, what else?

“Human Evolution and Human History: A Complete Theory” lives up to its bold title: it’s one of the most thought-provoking academic articles I’ve read. The argument is that the central trend of human history is towards increasingly large coalitions, from the hunter-gatherer band to the global empire; and that this trend can be explained by a single factor, the increasing range of weapons, from the spear to the ICBM.

If that is true, it will mark a decisive break between two modalities of liberalism: the political-theory, human rights, idealist modality; and the practical, economic, trading modality.

In the 18th century these seemed to go together. If a country had freedom of speech, assembly and contract, then it wouldn’t just score highly on human rights indices — it would get rich. This idea was the basis of British liberalism in the 19th century. It survived well, despite some dangerous challenges, in the 20th century. It was expressed by Fukuyama’s thesis in The End of History and the Last Man, that free markets and liberal democracy together were the endpoint of history.

But now China, which doesn’t care for liberalism or human rights, may become the linchpin of a new free trading system. If so, it will be partly because of American mis-steps. But also because today, market size gives you more efficiency than liberal policy.

In some ways, the experience of socialism was misleading in this regard. Socialism was so antimarket in its policy that it simply couldn’t generate efficiency gains, beyond the initial push for heavy industry under Stalin. But most real polities are on a spectrum between this extreme and pure libertarianism. The difference between contemporary China and the US with regard to market efficiency is one of degree only — and often not to the US’s advantage.

My generation, which grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, often misses the new importance of scale. Our basic model of the world was that efficiency was driven by market competition between many firms. Scrappy startups and conversely, lazy giants loomed large in our imaginary. That seemed to fit the first wave of innovation, around the internet bubble of 2000. We didn’t realise just how big the winners of that era would become. Or, we thought they would become lazy in turn and ripe for attack from new startups. But consider Google. While it can certainly feel like a lazy incumbent in some contexts — search sucks in 2025 — it has also become a frontier player in AI and self-driving cars. Its massive scale gives it the data to use as raw material, and also lets it think long-term, hiring top-level academic researchers to tackle fundamental problems.

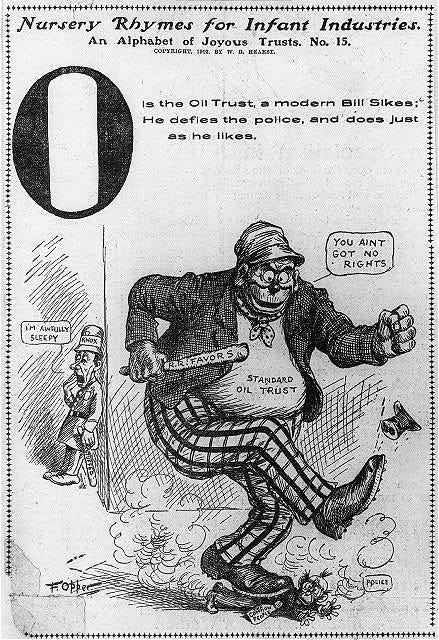

This is not the first time liberalism has been challenged by scale. The turn of the twentieth century in the US saw the growth of continent-wide corporations. They innovated — developing modern management and Taylorism — but also meddled in politics and tried to establish monopolies by fair means and foul. Then too there was a trend towards authoritarianism, not just in Germany and Russia but also in the US, where Franklin Roosevelt created a new administrative state and challenged the Supreme Court. Ultimately, US liberalism was reshaped but survived in its new form (though libertarians might consider the cost was very high). I speculate that then too, the new power of economic scale played a role in reshaping politics, although I don’t know enough about the era to be sure; certainly, the monopolistic nature of capitalism then must have made socialism more plausible.

My guess would now be that the outcome this time round will be less favourable. The authoritarian challenge from China seems more vigorous (Russian socialism really was a dead end) and more securely founded (Japan and Germany were both trying desperately to capture more population and resources, whereas China can relax on that front). And Trump is no FDR. But prediction is hard.

One thing I am sure of: liberals need to understand the strengths of the opponents they face, and the economic forces behind them. We live in a Zero to One world. Peter Thiel is right about that. Liberals need to rework their ideals to face the benefits and challenges of the world of scale.

If you found this interesting, please help good ideas to spread by liking and sharing it. Also, why not subscribe? Subscribing helps me to keep writing and producing ideas. About half my newsletters are paid or partly paid. A paid subscription costs just £3.50/month (about $5). Yearly subscribers get a great big 40% discount, plus a free copy of my book.

Well, it failed because Trump scrapped it.