What did the printing press do in early modern Europe?

I and Mich Tvede have a new working paper out called Technology of Cultural Transmission I: the Printing Press. This is one of a series of papers growing out of my work on Wyclif’s Dust the book. Hence the “I” in the title: there are sequels to come.

We start from a puzzle about early modern printed books.

There’s a standard story about the printing press, which is that it helped spread ideas faster. Economists, who think of technical innovations as a, or even the, key independent variable in generating economic growth, naturally think of it this way. So do many modern historians. This story goes back to the Marquis de Condorcet’s Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind, which he wrote in hiding before he was executed by the Jacobins:

These multiplied copies, spreading themselves with greater rapidity, facts and discoveries not only acquire a more extensive publicity, but acquire it also in a shorter space of time. Knowledge has become the object of an active and universal commerce.

In the largest sense, this story must be true. Of course print spread knowledge! Until this generation, it was essentially the only way of spreading knowledge, bar the age-old method of direct observation and apprenticeship.

Here’s the puzzle. If the press is all about scientific knowledge, why are about half of all early published books about God and religion?

You can easily dismiss this as follows. “Sure, people back then were very religious, news at 11. But that’s irrelevant to progress and economic growth. What mattered was how the printing press disseminated science.” In economists’ terms, religious books were just consumption goods, no more important than other early modern arrivals like coffee, sugar, tomatoes, or codpieces.

We disagree, for several reasons.

First, lots of early modern printed matter is “for consumption”, and it doesn’t look much like the religious stuff. There are romances and tales of ’orrible murders, there’s poetry and song lyrics, there’s Aristotle’s Masterpiece which was the early modern equivalent of Playboy. People back then liked to read the same stuff they like today! Religious tracts don’t obviously fit in here.

Of course a serious economist will respond that we’re taking the idea of consumption goods too literally. Gaining utility from something just means you choose it, and that applies as much to earnest religious material as to the fun stuff. Sure, we understand that, but go with your intuition. Are people really reading the the Plain Man’s Pathway to Heaven just for kicks? It’s 352 pages. Try it yourself. We think a better explanation is needed.

Second, there’s external evidence that the printing press caused more drastic changes than, say, the coffee grinder. Cities with more printers saw more Protestant publications. In turn, Protestantism increased literacy, especially women’s literacy, and possibly affected economic growth (an old argument which has been rejoined by recent economic historians).

Most importantly, look at what this religious material was, and how it was read.

Reading then wasn’t like reading now. Print material was rarer and more precious. There were no backs of cornflake packets. Reading was correspondingly intensive. As a marginal note in a contemporary book put it:

This whole book... continually, and perpetually to be meditated, practiced and incorporated into my boddy & souwle.... by perpetual meditations, recapitulations, reiterations... sounde and deepe imprinting as well in ye memory as in the understanding….

A tailor’s apprentice staying in Coventry found a history of Britain in his master’s house; over three months, he learnt most of it by heart. Protestantism in particular made intensive reading, especially of the Bible, central to religion.

Reading wasn’t always private, either. Householders read to their children and to their servants and apprentices. Puritan groups would hire lecturers in order to expound the Bible to them. Readers might follow the text, take notes on the sermon, and afterwards discuss it in the household. The sermon in turn might subsequently be printed.

Besides the Bible, there was a whole literature on self-improvement, including works which remained in print for centuries. In English there was Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, the Whole Duty of Man, and later Pilgrim’s Progress. There was also a specific literature on “household government”, with titles like A Werke for Housholders or Christian Man’s Closet or Oeconomia Christiana or Of Domestical Duties. These books specified the duties of husbands and wives, parents and children, masters and servants.

Such improving work wasn’t just for the rich or even just the literate. You could buy a “penny Godly” for tuppence. This period also saw the development of catechisms: short texts designed to be learned by heart. The Anglican catechism, learned by English schoolchildren from the 16th to the 20th century, ran in part:

My duty towards my neighbour is to love him as myself, and to do all men as I would they should do unto me: to love, honour, and succour my father and mother: to honour and obey the King and all that are put in authority under him: to submit myself to all my governors, teachers, spiritual pastors and masters: to order myself lowly and reverently to all my betters: to hurt nobody by word nor deed: to be true and just in all my dealings: to bear no malice nor hatred in my heart: to keep my hands from picking and stealing, and my tongue from evil-speaking, lying and slandering; to keep my body in temperance, soberness, and chastity: not to covet nor desire other men’s goods; but to learn and labour truly to get mine own living, and to do my duty in that state of life unto which it shall please God to call me.

Peter Laslett called these words “still evocative and familiar” in the 1950s.

Works like these passed on messages. They encouraged hard work and self-control; cooperation and trustworthiness; and specific, often unequal social roles. They condemned drinking and praised honesty. They encouraged servants to work hard even when they weren’t being observed.

They were designed, in economists’ terms, to change people’s preferences; or in the terminology of cultural evolution, to transmit advantageous cultural rules. The context was the early modern economy, where trustworthiness, honesty, sobriety and stable marriages were in demand. Partly because they were so rare: the History of Myddle, a seventeenth-century record of life in a small Shropshire town, has an index starting

Absenteeism

Abusive language towards parents

Accident, death due to

Adoption

Adultery

Aggression (see Fighting, Quarrelling, Homicide)

Alcoholism (see also Drunkenness)

... and that’s just the A’s. This was a time when employers had little ability to monitor their employees: no clock to punch in and out, no algorithm to optimize your Amazon delivery route. They had all the more need for intrinsically reliable employees. Communities too, benefited from sober and reliable citizens, and they often paid for this sort of enculturation. Some early nation-states started national literacy campaigns, whose aim was not technical education but citizenship, social order and political obedience.

In short, before the printing press transmits knowledge, it transmits culture. It changes who people are and what they want to be.

To see why this is historically important, imagine a world where the printing press doesn’t transmit culture. It’s only used for technical knowledge. OK, great, so the modern world still takes off, right? We skip all those pious Puritans and strenuous Jesuits, and get straight to Bacon and Newton and the steam engine.

But now you have a chicken-and-egg problem. There’s no point setting up a printing press to print technical books, until there’s mass demand for technical knowledge. But technical knowledge doesn’t start growing until people can swap ideas using books. What could be learnt technically from books in 1500? Eh, maybe accountancy, maybe some glassblowing. The vast majority of knowledge was, and continued to be, passed down orally among communities of skilled workers. It takes a very long time before formal, written knowledge becomes an important driver of economic growth — maybe even until the “second” industrial revolution around the 1870s, when the Germans start doing things with chemistry. Without the demand for religious, cultural print material, then, scientific printing might never have got started.

This is no mere hypothetical. It is approximately what happened in the Ottoman empire. The printing press was initially banned there. In 1729 it was reintroduced. You’d expect an explosion of printing. In fact, just 33 books are printed throughout the 18th century. The rate of printing only increases from 1802, when the Ottomans allow religious work to be printed.

In the paper, we go into early print material in depth. Then we introduce a macro growth model, with a traditional sector which doesn’t require technical knowledge, and a modern sector which does. Books and education come in two forms. Technical education only works in the modern sector. Enculturation — the sort of works mentioned above — increases your productivity in either sector. We show that for some parameters, you need the boost to productivity from cheaper enculturation, before people move to the modern sector and start using modern technical education and developing modern science.

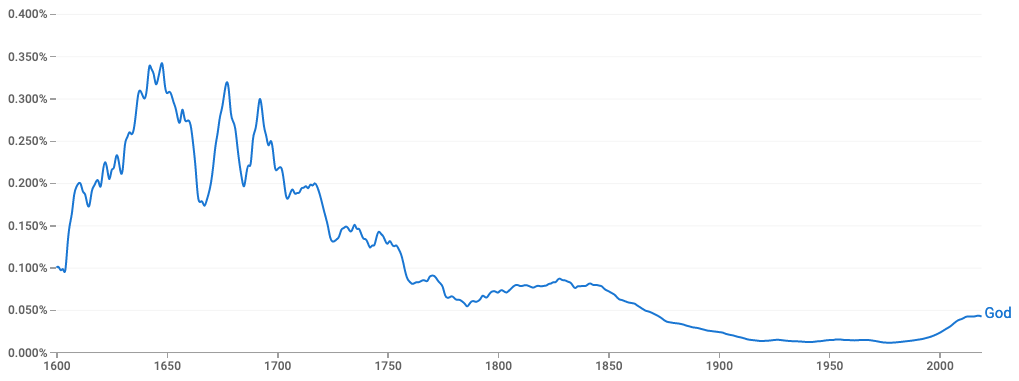

This theory explains the puzzle of the rise, then fall, in the number of religious printed books. According to it, religion in early modern Europe wasn’t just an unfortunate detour on the road to modernity. It was a bridge that helped to get us there.

Of course, this is just a theory plus some anecdotes! Empirical work is also needed to look at the content of early modern print and confirm whether it really did try to change people’s values. There’s a suggestive recent paper showing that cooperation-related language increased in the years leading up to the English Civil War. But there’s much more to do.

If you liked this, then I would love you to do three things:

Subscribe to this newsletter. It’s free. If you’re not sure, read more.

Share this post on social media. By telling your friends and/or followers, you’ll be doing me a huge favour.

Read about the book I’m writing. It’s called Wyclif’s Dust, too. You can download a sample chapter.

The increased availability of books as a mechanism for enculturation is an interesting one. But does the contents of the books matter?

A person's prior history of studying books is a signal of their ability to work at a difficult task without a lot of supervision. Their willingness to spend many hours reading is a signal of their industrious. The content of books will be driven by the fashion and culture of the day, i.e., customer demand is what sells.

Technical books came later because it took a while for nobles to realise that they could gain status by sponsoring their publication, much like they sponsored works of art.

The analysis in 'Setup' pulls equations out of thin air (references would be good), and makes lots of assumptions the free flow of people, ideas and book contents being uniformly of practical use. There does not appear to be much connection with the earlier text.