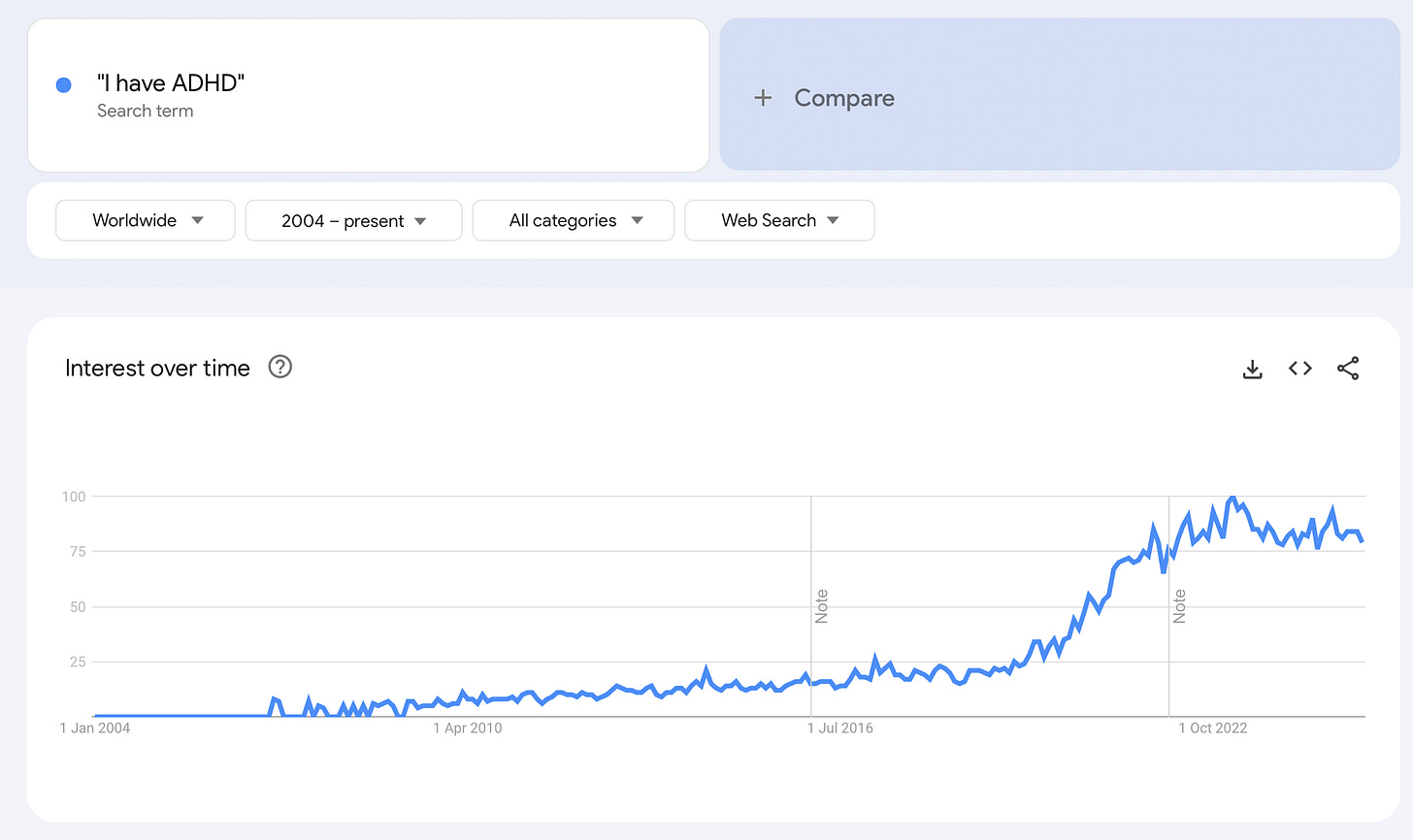

We have developed the collective habit of diagnosing ourselves and people around us with mental health disorders. You’ve probably noticed this yourself, but here is some evidence from Google trends:

These are web searches rather than web page content, so they are private not public, but I think you’d see the same trends for posts or whatever.

Is this a good thing? I can see some upsides:

Diagnosing your mental health issues is definitely not the worst approach! Saying “I have depression” frames it as a problem which you can potentially solve. In my experience, this is a much better and healthier framing than many others—better than drowning in it, ignoring it, romanticizing it (as The Magnetic Fields sang, making a career of being blue) or blaming other people for your feelings.

Sometimes it is simply realistic. Think of the word “depression” versus “sadness”. “Depression” acknowledges that your reactions to the world may be out of kilter, that just maybe, you are not unhappy because of the dreadful state of international relations today, the death of a dear friend’s canary, or whatever, but because you have a tendency to get unhappy too easily.

Applying these labels to third parties is often better than just blaming them for their behaviour. It may be a road to empathy.

These diagnoses link to a body of medical knowledge, at least some of which may be useful, some of the time. If you are indeed bipolar, drugs or talking therapy may help.

But you know all these points already, they’re common knowledge. I think the pendulum has swung too far, and the disadvantages of this approach are now being underpriced.

Intuitively, it’s tasteless. It is an invitation to trend-chasing and to self-obsession, indeed self-aggrandizement. An acquaintance of mine often used to say of some other person that he was “on his epic”. But most of us are not Odysseus. We are more like Mr Pooter. “Discovering” our own syndrome puts us on our epic, specifically: the Quest to Find Ourselves.

It opens the door to bullshit. When someone tells you they have autism, ADHD, or whatever, is that a serious diagnosis or something they saw on Tiktok? Who knows? Of course, it would be deeply offensive to ask. Solve for the equilibrium!

Sadly, it also elicits bullshit from mental health professionals—a fairly fluid category—who will step in to supply the demand for diagnosis, with varying mixes of cynicism and self-deception.

More seriously, it encourages the sufferer to focus on fixing a deep problem rather than changing their behaviour. A person who is socially awkward and unaware of other people’s feelings can try to be less rude and more empathic, or he can try to cure his “autism”. The benefit of the first approach is that it is often doable, even without addressing any deeper issues. In fact, trying do it may even resolve the deeper issues! As the saying goes, fake it till you make it. The risk of the second approach is that it devolves into an endless, and perhaps not entirely serious, quest—though the person concerned may take it very seriously.

I have dealt with depression for my whole adult life (and here I am, going against this post’s advice and telling you all about it). It is entirely real and serious, and a very nasty chronic condition. I am confident that the medical/psychological point of view is the best way to think about it overall. Yet, one of my small breakthroughs came when I realised that I had in some sense spent a lot of my life sulking, and the less sulking I did in future the better. That is not the kind of perspective that the medical framework tends to foreground.

It’s the same when we apply this language to third parties: we focus on deep facts rather than behaviour. “He’s a narcissist” sounds unalterable. “He treats women badly” is not. Nothing will stop humans giving labels to other humans behind their back. But moral language, unlike medical language, contains a suggestion that behaving differently is possible—without therapeutic treatment. Think of it this way: would you start a conversation aimed at changing someone’s behaviour with “you’re a narcissist”? Probably not a productive approach. So when people say it behind someone’s back, we can guess that they just want to be nasty—or at best, to give a descriptive warning.

Labels like “autist” or “narcissist” do have a lot of useful descriptive power. But all labels do that. Back in the Freudian century, “anal retentive”, “penis envy” and “hysteric” could all be informative ways to describe a person, which doesn’t mean that the theory behind them was either helpful or true. Before that, so were “reprobate” and “sinner”.

Probably the most serious thing is that throwing terms like ADHD and autism around involves a discursive externality. When everyone clothes themselves in the authority of these terms, little by little, they become broader and vaguer. Eventually they are no longer useful to describe people with really extreme problems.

Freddie de Boer has written bravely and indefatigably on this:

In article after ponderous article, autism was described as a newer, perhaps better way of thinking, sometimes even a “new evolution” for the human species. Always, always, always, this navel-gazing fixated relentlessly on the highest-functioning people with autism. You could read tens of thousands of words in this genre without ever once being informed about the existence of those whose autism debilitates them.

The mental-healthism trend is a shame, because the move in the 1990s from Freudian therapy towards cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) was in the opposite direction. Patients were told to stop focusing on deep problems from their childhood, and work on actionable fixes in the present: trying to behave differently and see things differently. Now we have a new set of deep problems, maybe they’re even in our genetics or whatever, also maybe they make us interesting and diverse. This is overblown and deserves pushback.

I am highly dubious that "Autism spectrum disorder' is a continuous spectrum or that its different components necessarily have all that much in comon with each other. The 'High Functioning Autism / Asbergers" individuals have been around for a very long time and have tended to all but dominate certain fields. This was true when I went into Physics / Engineering 50 years ago and from what I see, it is still true. It is my understanding that it was true well before my time. Yes, I was eventually diagnosed as an Aspie - as a side effect of the evaluation of my youngest daughter, but my extended family is full of probable aspies for generations. No, we are not well suited to high socialization, high extraversion activities, but our strengths match well with other valuable roles, so we do pretty well. The question is not if we are stock, standard social extraverts such as seems to be desired, but if we can find productive niches where our talents and aptitudes are well matched.

Just because somebody is different does not mean that they have a mental halth problem.

Well, respectfully, I respect your assessment of yourself as I do everyone else´s: finally one self is the better judge of one self by the mere oversupply of evidence, of data to do so: Judge oneself.

Being said, the Mind is not real:

https://federicosotodelalba.substack.com/p/beauty?r=4up0lp

I have seen, and narrated how believing the mind is real when it is not, and using empathy based on Mental Disorder Labels, even proper as state of the art called "diagnoses" or "formulations", can lead to Radicalization, Fundamentalism and at least Verbal or otherwise Psychological Violence. It is a two parts writing, but here is the First:

https://federicosotodelalba.substack.com/p/hey-my-haters-hear-me-out?r=4up0lp

Comparing the Radicalization process of in Jail Fundamentalists, Terrorists, with what I´ve experienced with Mental Neurodivergent Jihadists, respectfully said this is Hyperbole and Satire, I am confident it is the same process: Fundamentalism and Radicalization.

Such Neurodivergent Radicalization process includes Activists,Influencers such as Key Opinion Leaders or Actors/Actrices and the like, denigration, dehumanization, violence, indoctrination, isolation, puritanical non-religious thinking, etc.

And it leads to Alegal, Asocial, Amoral and Areligious ways of behaving, in at least these three original posts of mine I have argued why:

https://open.substack.com/pub/federicosotodelalba/p/a-comment-to-pathologizing-the-creative?r=4up0lp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/federicosotodelalba/p/a-comment-to-a-final-reason-to-never?r=4up0lp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/federicosotodelalba/p/comments-on-what-does-it-feel-like?r=4up0lp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

Basically my argument is believing the mind is a real thing when it is not, leads to the acceptance of Mental Disorders as a real true thing they cannot possibly be.

And by doing so, it replaces the Four Normative Systems which govern how Humans are supposed to behave with others: Law, Social Norms/Tradition, Morality and Religion.

And the more illustrative example is Trans Ideologies and Gender Dysphoria Labels or "Diagnoses", even if accepted as given or done appropriately per the State of the Art of those Mental Disorders:

https://federicosotodelalba.substack.com/p/the-trans-world-reflects-what-is?r=4up0lp