… and then one day he was back, straddling the strange machine of nickel and ivory as it solidified. He had an extraordinary helmet on his head, and he was still wearing his bicycle clips.

“I decided,” he said, “that to understand that strange future, I must seek its roots. I twisted the dial and flung myself forward, less far this time. The arc made by the speeding sun had barely moved in the sky, before the machine came to a halt. I hid it in a shed on the banks of the Thames, and went to seek the human race at the start of their long species-divergence. And I found them!

I won’t bore you with the narrative of my investigations. The world I had arrived in held no shadowy dangers, no underground cannibals — at least in the parts I visited. Suffice that I travelled through space as well as time, from Paris to Portland, from Boston, Massachussetts to Boston, Lincolnshire. Yes, the Eloi were already there, and the Morlocks, too!

The Eloi of this era were not yet the inarticulate, playful elf-creatures of my first adventure. They still dared great feats of science, and they cared for learning, perhaps before all else except one thing. But already, some of them had started to live in the rainbow world of their own imagination, and to take that as their only reality.

They believed, for example, that they could change sex at will, putting on Man and Woman just as we dress for dinner. Some of them even invented new sexes for themselves, and gave themselves curious pronouns. It sounds like children at the dressing-up box, doesn’t it? But they took it seriously — very seriously. Woe betide you if you misspoke their pronouns! This was a faux pas almost as bad as speaking of the dark would be to the later Eloi…. After all, is it any more ridiculous than the absurd, constrictive uniforms we force the sexes to wear?”

“Surely,” broke in the Journalist (we had all gathered in the dining room, as we had done every month since the Traveller left, in a sort of night-watch-cum-wake for our friend), “surely reality must intrude at some point. I mean — you can call yourself what you like — but bodily reality — ”

“Bodily reality can be changed,” replied the Traveller with a curious smile. “Let me tell you more. They are conquering the devil of Drudgery. Of the Eloi, few work more than half their life, and they live longer than we, Progress having continued. Even when they work, it’s not real work. They sit at desks, in front of the magical typewriter-tools of the future. These typewriters bring them whatever they need: any knowledge, the latest news, a conversation with their friends, a message from the rulers of the world… all at their fingertips! So of course, they hardly need to work, and many hardly do. They spend their time firing short messages at each other, and gaining points for the best bon mot of the day. It’s just a huge game, going on all round the world, at every hour! You ” — he gestured at the shy, bearded guest — “would have loved it.”

“Or they take photographs and show them to each other. That’s another huge game, and many make a living from playing it. Oh dear, not real work at all! But that is the one thing they value above all else, more even than learning: creativity. The artist in their world takes first place, before the statesman, the thinker or the warrior.” At this the Very Young Man smiled (he had been published in the Yellow Book a fortnight by) and the Provincial Mayor coughed.

“But with all this leisure and play, they don’t seem as fresh and content as one would expect. The weakness and lethargy of the Eloi is in them, and what remains of the old world of constraint and labour tires them more than it would us. They’re always complaining about how hard they have to work. “I’m exhausted” is a saying with them, and if one dislikes anything, an opinion or a bon mot on the typewriter, that’s “exhausting” too!

Yes, they are extraordinarily emotionally vulnerable, even weak. They worry about their “mental health,” and they don’t mean real madness, but feeling tired or sad or upset. All of that they think of as mental health. But they really do seem to be more fragile than we would be. And violence! It terrifies them. Why, while I was there, a famous man struck another man because he had insulted his wife. Not even an honest haymaker, but an open-handed slap, really like a fight between two Covent Garden flower girls. Well, there was outrage! It was as if murder had been done. Of course, everyone tried to have the best bon mot about it.

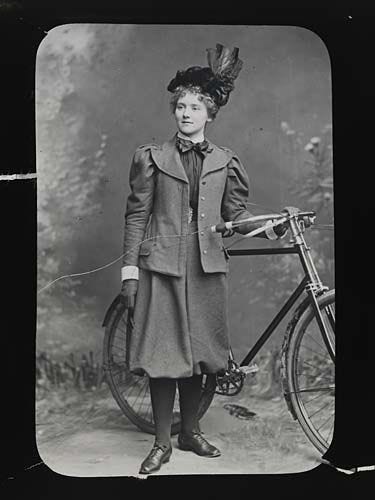

But the places they live are beautiful. They’re cities, yes, but without the muck and filth and smoke of the Great Wen. They don’t even ride in motor cars, the Eloi. They don’t need to! Everything is nearby, so they just bicycle. Bicycle to the coffee shop.”

Here the Editor broke in again. “How do they get all this stuff, then? It can’t all come via a magic typewriter. Who brings all the physical objects to these urban Elysiums?”

The Traveller’s face darkened, and a murmur went round the table. “Yes, the Morlocks. They are there too. Their lives are very different, already, from those children of ease and imagination! Like the Morlocks of our our own time, they have to work. Not always in factories or mines underground — there’s less of that than now. More often, they deliver things. They work in great mechanical warehouses, ordered around by great mechanical brains, sorting parcels to deliver to the Eloi, and they’re worked pretty near the bone, some of them. Or they drive motor vans, like the ones that Daimler are starting to make on the Continent. In between the Eloi on their bicycles, you’ll always see a Morlock on his van. Then, the Morlock women work too. All women work, in that world — and why not?” He looked around the room with an air of challenge. “But the Morlock women do real work, not like the Eloi. They look after old Eloi, and there are many of those, or they look after young Eloi, though there aren’t so many of those.

It's funny. Morlock work is much harder than Eloi work, but while the Eloi worry about having too much work, the Morlock worry about having too little.

Well, how do they get on, you’re wondering? They’re not at war, not yet — nor eating each other. But you can see the division. They live increasingly apart, you see. The Eloi in their cities on their bicycles, and the Morlocks, driving in to serve them in their motor cars and motor vans. Of course, the Eloi hate motor cars, and the Morlocks love them. The Eloi, for very good reasons, are trying to tax the Morlocks’ motor cars and their world-heating smoke. So already, once or twice, the Morlocks have invaded their cities en masse, in their cars and vans. The Eloi can’t stand it! They find the noise and the smell exhausting.

What’s worse, I think, is that the Morlocks don’t trust the Eloi any more. You see, the Eloi rule everything. They’re the clever ones, and they all know what to think because they exchange bons mots all day on their typewriter-tools. But the Morlocks have typewriters in their pocket, too. They have to, so that the machines can tell them where to deliver parcels in their vans. And they don’t trust the Eloi any more. No, they’re spreading their own ideas!

And those ideas: by God, they’re stupid.

It’s not anything like socialism. It’s more like anti-Semitism — you know, the socialism of fools. The Eloi, you see, for all their childishness, live in the light. They understand the world, and they have time to find things out on their typewriters. But the Morlock are really in the dark, mentally if not physically. They believe anything… and they don’t trust the Eloi any more! They listen to their silly pronoun-talk and they don’t take it seriously. So then they hearken to even sillier things. They have Morlock leaders who pour all sorts of poison into their ears.

Those leaders… they’re worse than Morlocks. They are true creatures of darkness and terror. I’d call them, I don’t know — goblins… no, Orcs. They’re the Orcs from Beowulf. What a choice for a Morlock! Trust an Eloi, or an Orc!”

The Psychologist rubbed a finger along his cheek. “Is it the start of the inevitable, then? Will they slide down from there into the world you first saw, with the poor children in their playgrounds of light, and their cannibal twins in the darkness underground?”

The Traveller shook his head. “Can the future be changed? I don’t know. Can it be put off, at least? Are the two kinds doomed to misunderstand and mistrust and hate each other, or can they come together again? Can they stand together, when they have to, against the very worst of people? … Can I save my poor Weena from the fate I led her to?

In any case, I learned all I could. At last I retrieved the Machine and drove back through time, through the first — last? — London pea-soupers, through war and destruction, to the present. (Strangely, at one point in my rushing descent, I thought I was overtaken by a pair of drunken Chinamen.) I know I must go again, to find my love. Then, maybe, I’ll find everything changed by my own actions, and the warning I brought back. For better or worse! For better or worse! But I have to try.”

He stopped and leaned back. We stared at his pale, wrought face.

“What did the Eloi think of you?” said the Very Young Man, after a pause.

“Hard to know. For some reason, they got very upset about this.” He stroked the ivory on the machine. “Such a lot of fuss about an elephant. Anyway, I’m exhausted (there, I’ve caught their figure of speech!) and I need a lamb chop. One gets so tired of vegan food.” We had no idea what he meant, but we laughed and called for Mrs Watchett. He unbuckled his bizarre headgear and stepped off the machine. I noticed that on its nickel body were glued a number of little paper advertisements. Most of them seemed to be for coffee shops, and one was in the shape of a unicorn.

If you liked this piece, then I would love you to do three things:

Subscribe to this newsletter. It’s free. If you’re not sure, read more.

Share this post on social media. By telling your friends and/or followers, you’ll be doing me a huge favour.

Read about the book I’m writing. It’s called Wyclif’s Dust, too. You can download a sample chapter.