I like to read modern poetry. As a result, I am regularly bothered by the fact that a large strand of modern poetry is just very obscure. Here’s part of Paul Celan’s poem Die Engführung:

Ich bin’s, ich,

ich lag zwischen euch, ich war

offen, war

hörbar, ich tickte euch zu, euer Atem

gehorchte, ich

bin es noch immer, ihr

schlaft ja.It’s me, me,

I lay between you, I was

open, was

audible, I pulled at you, your breath

obeyed, it’s

still me, you’re

sleeping though.

What the hell does that mean?

The general critics’ view of this passage is that the speaker is “personalized time” who “ticks” [tickte] at the people spoken to. This is the angle taken by Karl Knausgaard, who devotes a big chunk of the last volume of his autobiography to a close reading of this poem. But it’s hard to know what that means, and it rather reminds me of Craig Brown’s Knausgaard parody:

We cannot ecape time, it is a fundamental condition of our existence, and we are therefore excluded from non-time, from timelessness. In the kitchen, there is a clock on the wall and when I look at it, it tells me the time. But it does not tell me the time with a voice. It cannot speak. Or, if it can speak, it chooses not to, preferring to remain dumb, for its own reasons, possibly to do with shyness, or a trauma suffered when it was a little child, or a little clock, better known as a watch.

A nicer interpretation comes if you step back from the verse’s meaning and listen to the tone. The language and syntax is very simple. This is a child speaking. The setting — “I lay between you… your breath obeyed” — suggests that it’s a child talking to its parents. Celan was a Jew from Czernowitz in the Ukraine, and his parents were murdered in the Holocaust. Ticken can also mean “touch”, or I’ve tried “pull at”. I think what is going on here is on one level quite simple: the survivor’s guilt of a child whose parents didn’t take the chance to escape, partly because they had a child to look after. (Earlier the poem says “Something lay between them, they couldn’t see through it. Couldn’t see, no, spoke of words. None of them woke up, sleep came over them...” It’s a description of that common post-war question — why didn’t they get out when they could?)

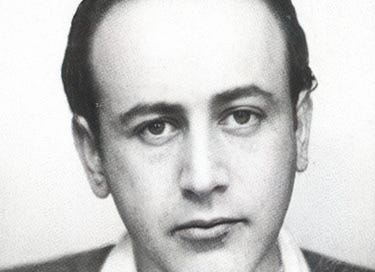

Celan is a formal genius, deeply immersed in European culture, who built complex structures into his poetry and who returns obsessively to a set of basic metaphors — stones, eyes, water — of which the meanings emerge throughout his work, and which cannot be neatly summarized. But what’s interesting about his work isn’t how clever it is, or that it tells us deep things about poetic representation or whatever (critics who read it this way end up blathering). It’s interesting because he is trying to explain himself, while making no compromise with the reader — without the half-truths that inevitably come when you bend towards someone to communicate. So it’s obscure for a reason. But the emotional power of his writing is as important as the formal intelligence.

Geoffrey Hill

There is a lot to say against obscure high-modernist poetry. At its worst, it becomes a game of who knows the most literary allusions. This is a pointless way to communicate, and in the age of Wikipedia it doesn’t even fulfil the purpose of making the author seem clever, because anyone can look up the relevant Greek myth or whatever. Or it’s deliberately cryptic, which is a form of passive aggression, which deliberately shrinks the poet’s audience, and which runs the risk that beneath the complicated camouflage, the underlying ideas might not be that clever. So, for example, I’ve found almost nothing worthwhile in John Ashbery or J. H. Prynne. Poems like that remind me of what Brian from East 17 said about his contemporaries in drony, inaudible indie bands. “They’ve got the technology, man, why don’t they use it?”

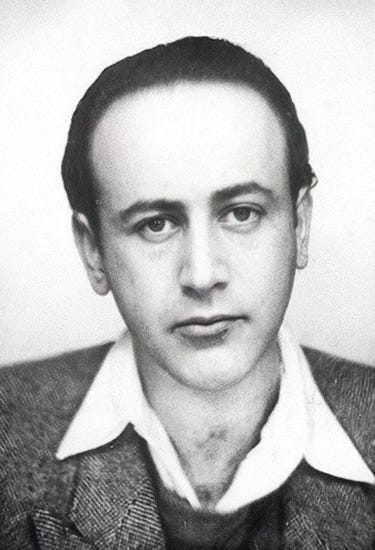

But some people really do have interesting thoughts, and need a complex language to express them in. Then, it’s often not the complexity itself that makes them interesting. Geoffrey Hill is obviously someone who can’t help reaching for Ruskin or some 14th-century mystic to explain himself. But here he is in Mercian Hymns, his sequence of poems mixing his childhood with King Offa:

‘Not strangeness, but strange likeness. Obstinate, outclassed forefathers, I too concede, I am your staggeringly-gifted child.’

So, murmurous, he withdrew from them. Gran lit the gas, his dice whirred in the ludo-cup, he entered into the last dream of Offa the King.

This is funny, alive, direct and mysterious. Celan is difficult because his thoughts are intrinsically difficult, and simplifying them would betray them. Hill is probably a good poet in spite of his obscurity, not because of it, but he is still worth chewing at.