The age of extremely horizontal norms

Social norms coordinate society. Think of the speed with which firms left the Confederation of British Industry after its head was embroiled in a sex scandal, for example. Many organizations could potentially fulfil the role of representing big business in the United Kingdom; after this public drama, a large chunk of the economy was able to simultaneously decide that the CBI shouldn’t be the one.

Norms have two aspects. One is vertical. Norms are transmitted “down” the generations. Kids are taught norms early in the life course: that’s when they learn fastest and are most malleable, and when their enculturation has the longest-lasting benefits. Much later, they pass them on to their children in turn.

Societies also try to keep their norms consistent over time. In the past this was especially important. To understand why, think of a group planning to climb down off a mountain at night, in a snowstorm. The mountaineers won’t be able to communicate during the climb itself. So they need to make a very detailed, careful plan beforehand, and keep to it rigorously so the team can work together.

Historically, large-scale societies faced a similar problem. They needed to be able to coordinate their members’ actions using norms. But to make sure everyone had the same norms, they had to start with a precisely-defined normative system, and transmit it with high fidelity down the generations. These societies’ norms had a strongly “vertical” character.

For example, the Romans were extremely traditionalist about their morality. Note, traditionalist: they were self-conscious and deliberate about preserving the mos maiorum, the customs of the ancestors. The Romans were highly aware of cultural differences, because they’d met (and conquered) so many different cultures. But this self-consciousness and even relativism co-existed with cultural conservatism. Everything new was bad. When Pliny quoted the saying ex Africa semper aliquid novi, there’s always something new from Africa, this was not a compliment. This traditionalism allowed two Roman citizens, educated at opposite ends of the global empire, to share a common moral framework, even though their “latest common cultural ancestor” may have lived several generations back.

Writing of course helped with this hugely, and the civilisation that replaced Rome was based on a single book. Again, great emphasis was placed on making sure it was just one book, in an age when text could not be mechanically reproduced, but had to be copied out laboriously in editions of one. Here’s the Book of Revelation:

If any man shall add unto these things, God shall add unto him the plagues that are written in this book: And if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book.

In other words, book religion, the world-historical cultural form shared by Judaism, Christianity, Islam and others, may have simply been a response to the technological limitations of copying text. It’s a weird thought which makes some kind of technological determinism seem tempting.

I’d hypothesise also that fights over images, which recur in Christianity and in Islam, are related to the same dynamic. Religious images didn’t allow precise copying, unlike the digital technology of letters underlying the written word. Iconoclasm, image-breaking, was a way to protect uniformity from images’ centrifugal, localising force.

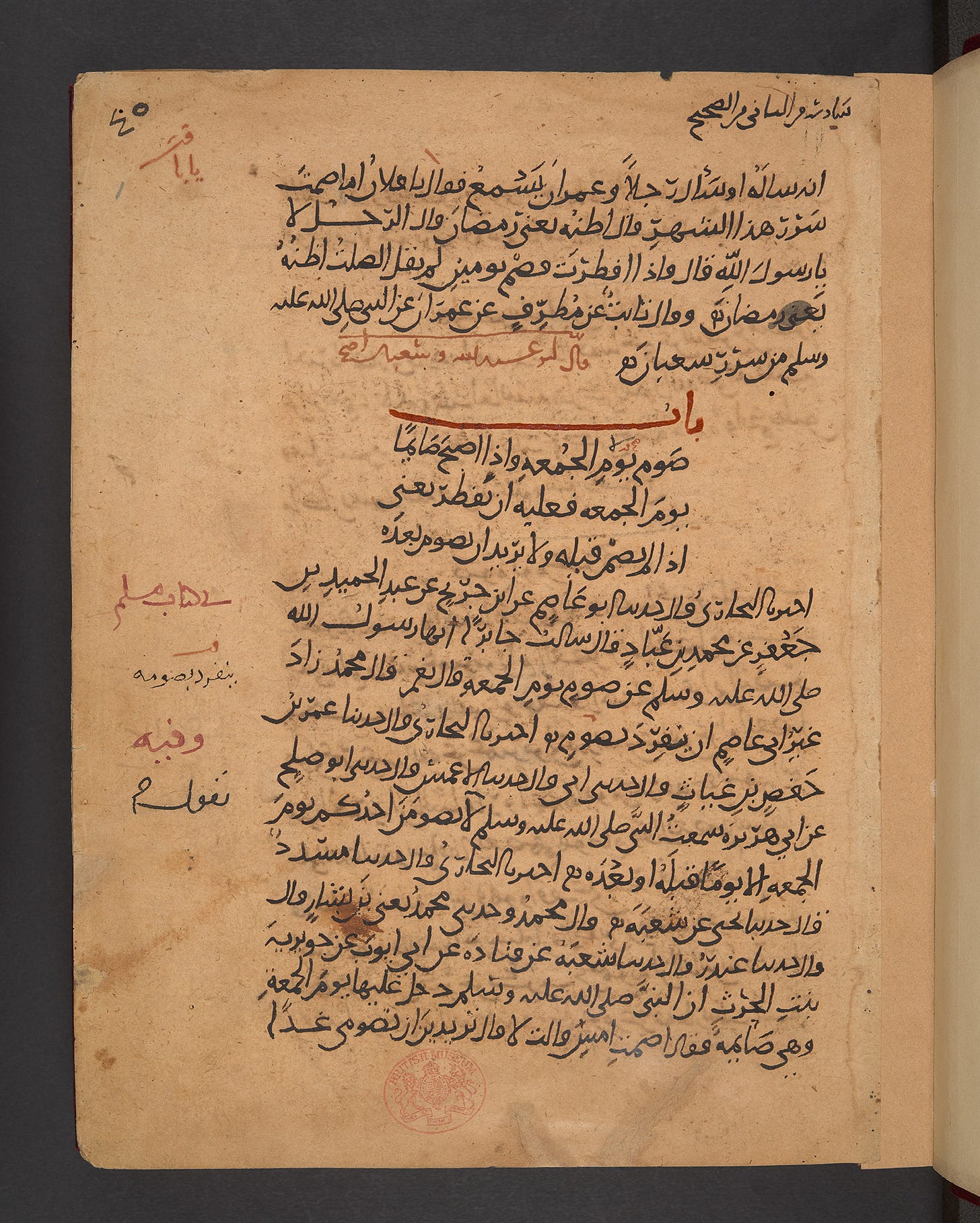

Islam went to extraordinary lengths to extend uniformity beyond a single book. Religious jurisprudence consisted of chains of Hadith (sayings of the prophet). These Hadith had to be learned by heart from a teacher, along with the chain of previous teachers, back to the original. A whole science of cultural transmission grew up to analyse the credibility of different chains, including the quality of the source, the way it was transmitted across each chain, and the number of independent chains. This practice shows how much effort a pre-modern, large-scale society (the largest) put into faithfully reproducing culture, at a very granular level, across space and time. Norm transmission is a serious business!

The world is flat

The second aspect of norms is horizontal. Norms spread from peer to peer. They work better when they have many people to enforce them — better still when it’s the entire group. So they gain power from being widespread. Conversely, individuals want to be in sync with people around them, so as to avoid social disapproval. This means that norms, like fashions, can spread fast.

Modern technology has greatly strengthened this horizontal aspect of norms, and weakened the vertical aspect. Think again of our mountaineers, and now imagine that they have walkie-talkies. Suddenly, they become much more capable of coordinating and collaborating on the fly, in response to changing events and conditions on the trip down the mountainside. In turn, this means they needn’t pre-specify the plan in so much detail beforehand. Communication has given them flexibility.

As a result, we now live in a normative age. This contrasts with the 1980s and 1990s, which seemed at the time (and in many ways truly were) a period of anomie and social disintegration. But today is normative in a particular way: our norms are unprecedentedly horizontal.

Future cultural historians will look back on the 2010s and see a Cambrian explosion of normative language. Gaslighting. Punching up. Punching down. Sealioning. Doxxing, deadnaming, gendershaming, “normalize X”… these yay-, and more often boo-, words, emerged to police the new world of online discourse, or to police the whole social world via online discourse. Who needs the Ten Commandments? (Quick check for traditionalists: can you list them?)

Extremely horizontal norms have benefits. They let society turn on a dime. Think about how fast Western countries formed a consensus about the Ukraine war, for example:

Hopescrolling

In 1942, Paul Éluard starts to write a love poem. Sur mes cahiers d’écolier Sur mon pupitre et les arbres Sur le sable sur la neige J’écris ton nom On my exercise books On my desk and the trees On the sand on the snow I write out your name

I think this was a genuinely bottom-up phenomenon: European politicians repeatedly found themselves playing catch-up with public opinion on military support for Ukraine. This sudden change didn’t just push policy in one direction; it reorganised the whole of The Discourse. Liberals rediscovered their combative cold-war roots. The left split, and Tankies became the object of widespread derision. The same thing happened on the right: the war divided American republicans and the European right, including populists. Francis Fukuyama suddenly came back into fashion, but instead of the old, complacent idea of Fukuyama who predicted the inevitable end of history, he was reimagined as demanding it.

It’s pretty obvious by now that extremely horizontal norms also have their downsides. The twenty-first century has had its witch-crazes, just like the seventeenth. This time round, fewer people got burned (but many lost their jobs). Horizontal norms are very vulnerable to fads and cascades. In the extreme, they can devolve into cultlike behaviour where anyone who disagrees is expelled from the group. Smart people are if anything more vulnerable to these phenomena. The craziness of some of what the New York Times prints compares pretty well with QAnon. And then there’s academia. Don’t get me started. (The curse of academia and similar institutions is that sometimes sheer bigotry can get you not only retweets but an actual job.)

More generally, norms are a tool for cooperation and coordination, and cooperation is still subject to the logic of collective action. In the end, norms will help groups to cooperate, not the world as a whole, and there’s no guarantee that this kind of cooperation will increase welfare.

The printing press was the last technology to reorganise social norms. It caused a kind of social explosion in the shape of the Reformation. (Martin Luther was probably history’s most successful pamphleteer.) Eventually, existing institutions — like Renaissance kingdoms and the Counter-Reformation Catholic church — recuperated the power of the new technology, and society stabilised, although some of the radical vision was probably lost. I would expect the same to happen in the coming decade. The disruptive force of extremely horizontal norms will eventually be tamed and integrated into the fabric of our societies, including our states. So the outcome won’t be as good as early internet idealists hoped, nor as bad as the fears of the chaotic 2010s. Nature will heal.

Will vertical norms come back? That’s much less clear. General rules are always compromises. They trade off appropriateness to a given situation against applicability across many situations. Quicker communication pushes against this trade-off, in favour of more situational, context-specific ways to agree on what to do. And if economic growth is faster than it used to be, then we might expect cultural change to be faster too. That change can make old norms obsolete.

On the other hand, I hope not! The vertically transmitted norms of earlier societies are an extraordinary collective achievement. Without their context, little of the art (or anything else) of those societies makes sense. It would be terrible to lose our connection to this past. And, since many of these ideas have lasted thousands of years, they must have something tough and durable about them. It would be unwise to count out even the most extreme kinds of “vertical norm”, like those embodied in intense religious communities. After all, contemporary society has not yet proved its staying power against these older rivals.

Here is an earlier, more general piece about social norms:

Social norms: the downside

If self-interest is the engine of society and the master key to social science, then social norms must come a close second. Humans are rule-followers who care deeply about what others think of us. Internalized rules are probably a key mechanism enabling us to pursue our goals and interests. The study of these rules, in particular the moral rules that so…

If you’re interested in the history I’ve touched on, my book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present goes into more detail. You can get it here.

And, if you liked this article, please share it with others: