Revenge of the Edwardians

Forerunners of modern social science include (checks notes) Rudyard Kipling and Robert Baden-Powell?

“They fuck you up, your Mum and Dad” wrote Philip Larkin in This Be The Verse. As a teenager, I took this line seriously and learnt the poem by heart. But it spread the blame fairly. The real criminals were the narrator’s Edwardian grandparents, “who half the time were soppy-stern / And half at one another’s throats”.

Larkin was parodying the 1960s image of Edwardian society as buttoned-up, Puritanical, hypocritical and nationalist. (This image would have surprised the multi-mistressed Edward VII.) The sixties wanted to blow all that up, and social scientists were allies in the task. In the US from Berkeley and a keen supporter of the student demonstrations, in the UK from a New University like Essex or East Anglia, the social scientist wore jeans and a turtleneck and was on the side of progress and liberation. Psychologists would get you to admit secret longings like (ew!) having sex with your mother. Sociologists did it at group level, and tried to explain why the working classes had not joined the revolution.

These images are still around today. Turning Point USA complains that universities are hotbeds of Leftism, and maintains a creepy watchlist of liberal teachers. The Twitter account @newrealpeerreview mocks whiffly social-science-as-personal-liberation. And yes, the vast majority of academics are left wing.

But modern social science has a strongly Edwardian strand.

Take that quintessence of Edwardian upbringing, cold baths and showers. Cold baths had been endorsed in the 19th century by the hydropathy movement. They were healthy for the body and the mind too, because they stopped you thinking impure thoughts. The Social Purity Alliance recommended a “cold bath every day”.

They are now back in fashion. Elite athletes regularly use them to cool down after exercise. They might also improve your immune system in the long run, making you less likely to call in sick for work. (This result comes from a randomized experiment. It is not just because the psychopaths who take cold showers also never pull sickies.) Researchers have even suggested cold baths as a depression cure. Softies may prefer the half-baked alternative: end your hot shower with a quick 30 seconds blast of cold. Other Edwardian health fads, like fresh air and cold temperatures in general, also really work: cold stimulates activity in brown adipose tissue, a.k.a. good fat, helping you to burn calories; outdoor walks make you feel happier and improve your self-esteem.

About those impure thoughts. I don’t want to frighten internet readers, but masturbation might actually be bad for you. At least, so argue Brian Park and his colleagues. They reckon internet porn can lead to a spiral of unrealistic expectations which makes real sex disappointing. These intellectuals have led the youth astray, and now there is a #nofap tag on twitter and a reddit subforum with half a million “fapstronauts”, dedicated to “rebooting” – abstaining from masturbation for a set period of time. Perhaps they could take advice from “Bobs” Baden-Powell, the short-trousered hero of Mafeking and father of the Boy Scout movement, in Scouting For Boys (1908):

The next time you feel the desire coming on don’t give way to it; resist it. If you have the chance just wash your parts in cold water and cool them down.

By the way, the alt-right-ish Proud Boys movement has a no-masturbation requirement for members. Allegedly they were turned on to the ideology by a black liberal comedian. Do not ask me to explain this.

The biggest Edwardian revival has to be sport. Sportsmanship was the centrepiece of the public school ideal, and of manliness more generally. Soft leftwingers reacted, dividing the world into philistine “hearties” and sophisticated “arties”. George Orwell remembered “the daily nightmare of football — the cold, the mud, the hideous greasy ball that came whizzing at one's face….” Now, driven by Western democracies’ fat bottoms, sport and exercise are again beyond criticism and pushed by public policy. This time even intellectuals have a favourite football team, and read Haruki Murakami’s book on jogging.

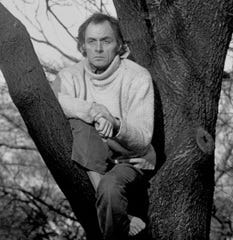

In psychology, the gurus have changed. R. D. Laing, the famed 1960s psychiatrist, wrote some of his work as concrete poetry:

I feel good

therefore I am good

therefore everyone loves me

Laing, pictured above in turtleneck and tree, founded a commune where schizophrenics could explore their creative side by painting with their own faeces. (The cause of schizophrenia was mothers, obvs.)

Today, Jordan Peterson has the same kind of public presence. His youthful followers are as weird as R. D. Laing’s: they call themselves “lobsters”, and produce memes at an obsessive work rate. But he himself wears a suit and tie. The first rule in his self-help book 12 Rules for Life is “Stand up straight with your shoulders back”. (Baden-Powell: “Stand upright when you are standing, and when you are sitting down sit upright, with your back well into the back part of the chair.”) Another countercultural hero is Vice Admiral William H McRaven (Retd.), writer of Make Your Bed.

R. D. Laing’s poem could be the motto of the self-esteem movement, which started in the 1970s. This took the common sense idea that it is nice to feel good, and made it into a social panacea. One advocate said he “cannot think of a single psychological problem—from anxiety and depression, to fear of intimacy or of success, to spouse battery or child molestation—that is not traceable to the problem of low self-esteem”. The high point was the creation of the California Task Force on Self-Esteem and Personal and Social Responsibility. This aimed to tackle Californians’ low self-esteem, not previously their best-known problem. One booster even claimed higher self-esteem would balance the state budget. That didn’t happen, and self-esteem turned out not to provide most of its touted personal benefits: it doesn’t enhance academic performance, improve people’s relationships, stop them taking drugs, or make them into leaders.

But this is ancient history. Today we have grit. Grit, advanced in the eponymous book by Angela Duckworth, consists of passion and perseverance for long-term goals:

Grit entails working strenuously toward challenges, maintaining effort and interest over years despite failure, adversity, and plateaus in progress. The gritty individual approaches achievement as a marathon; his or her advantage is stamina.

Or as Rudyard Kipling put it in his hit poem of 1910, If:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss….

Grit, unlike self-esteem, comes straight out of the Boy’s Own Paper, alongside pluck and derring-do. (The market for psychology books on those concepts is still open.) The Edwardians thought these manly qualities necessary for governing the empire. But perhaps the same virtues may help you run your internet startup.

Cultural studies, much mocked for their weak methodology and Queering-the-Hardy-Boys politics, have gone quantitative and conservative at the same time. The psychologist Jean Twenge has published papers mapping the rise of the pronoun “I” and the relative decline of “we” in books, and the increase in violence and nihilism in song lyrics. Terrifyingly, even the expressions on Lego men’s faces have got more fearful. Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) would have understood. He greeted the Great War as an escape from

half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary,

which turned out to be a little optimistic.

There is a deeper connection between us and the Edwardian era. Today, as then, public debate is linking social problems and individual behaviour. In Edwardian Britain, recruitment for the Boer War had revealed that despite economic progress, many working class people were still undernourished and unhealthy. The Scouts, and similar movements across the political spectrum, were attempts to respond by encouraging young people towards a healthy and “manly” lifestyle. The era saw increased support for state intervention to help the poorest. The science of public health was born. From origins in Victorian philanthropy, institutions like the District Nurse evolved into organs of officialdom.

Today, we are again making connections between poverty and inequality, and the social fabric. Coming Apart and Our Kids are respectively the latest books of Charles Murray, a conservative, and Robert Putnam, a social liberal. They say remarkably similar things. Both focus less on the income distribution than on outcomes like unemployment, single parenthood and addiction. Both point out that the rich have maintained traditional family structures better than the poor, and regret the resulting social fault lines. Lost In Transition, by four qualitative sociologists, describes the struggle of today’s “emerging adults” to articulate coherent moral values.

As in the Edwardian era, these concerns are linked to a resurgent concern with the nation, even to nationalism. Then, population health was seen as a matter of national security. Migrants to America were supposed to be undercutting native wages and Protestant values. Britain was becoming skeptical of the free trade it had championed in the nineteenth century, while Jewish immigrants were supposed to be “unfit” and to bring disease. Now, economists are reevaluating the effects of trade with China on American workers’ unemployment, the marriages they make, and their chances of dying early. And the opioid crisis, which kills a Vietnam of men every year, also has a national security dimension: China has been accused of supplying synthetic opioids to the US market.

Put at its broadest, though plenty of social science still has a progressive agenda, some emerging research endorses ideas more like those of our great-grandmothers. Why is that?

One underlying process is Western society’s slow mastication of 1960s ideas. Some of these ideas are steadily being digested and becoming part of us, like feminism and anti-racism – whatever the bumps along the way. Others are proving gristly and being spat out. The sexual mores of the 60s have looked steadily less attractive as #metoo has revealed their seamy, exploitative side. So has the unbalanced emphasis on personal fulfilment. Perhaps social science just reflects this sea change.

That is an uncomfortable thought for social scientists like me. Those of us who don’t think of ourselves as tenured activists often tell ourselves that we are scientists. Our business is discovering truths, not catering to the Zeitgeist. We talk about “hypotheses”, “experiments” and “theories”. Our papers contain what sound like scientific laws. Are we kidding ourselves?

I hope not. Sure, our claims to discover universal laws can be pompous. What chutzpah to go from experiments run in our WEIRD societies – Western, Educated, Industrialized Rich Democracies – to grand conclusions about human nature! Don’t we understand that people live in history and that culture affects how we behave?

But there is a humbler scientific ideal, which is just that of knowing you might be wrong, and trying honestly to find out. One of the comforting facts about the self-esteem movement is that it was eventually undermined by its own data. When the California Task Force’s research team wrote up its final report, it had to admit “one of the disappointing aspects of every chapter in this volume . . . is how low the associations between self-esteem and its consequences are”. Perhaps social science is making some slow progress.

If so, we shouldn’t be surprised that it has come full circle. Doing science about humans is hard; we are complex and unpredictable. On the other hand, as human beings, we are smart about each other. Our common sense is often a good guide to society, as it isn’t to, say, particle physics. In the Edwardian era, Western wisdom was still encoded in pithy sayings which schoolchildren had to copy down for handwriting practice. In another famous poem, Kipling called these sayings the Gods of the Copybook Headings. Many of the great twentieth century innovators, from Freud to Piaget, wanted to overturn this common sense, to show that rigorous science could understand humanity on a deeper level. But they often overestimated how scientific they really were. Sure, Freud thought of psychoanalysis as a science, but he never ran a randomized controlled trial or even collected systematic data by modern standards. Today we have more powerful tools available: better statistics, more computing power and more data. Maybe it is unsurprising that our new ideas are closer to the Edwardians’ Copybook Headings. As Kipling points out, those ideas have staying power.

References

Bartneck, C., Obaid, M. and Zawieska, K., 2013. Agents with faces – What can we learn from LEGO Minifigures? https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/16699/bartneckLEGOAgent.pdf?sequence=2

Barton, J., Griffin, M. and Pretty, J., 2012. Exercise-, nature-and socially interactive-based initiatives improve mood and self-esteem in the clinical population. Perspectives in public health, 132(2), pp.89-96.

Baumeister, R.F., Campbell, J.D., Krueger, J.I. and Vohs, K.D., 2003. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological science in the public interest, 4(1), pp.1-44.

Buijze, G.A., Sierevelt, I.N., van der Heijden, B.C., Dijkgraaf, M.G. and Frings-Dresen, M.H., 2016. The effect of cold showering on health and work: a randomized controlled trial. PloS one, 11(9), p.e0161749.

DeWall, C Nathan, Pond Jr, Richard S, Campbell, W Keith, and Twenge, Jean M, "Tuning in to psychological change: Linguistic markers of psychological traits and emotions over time in popular US song lyrics.", Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 5, 3 (2011), pp. 200.

Duckworth, A., 2016. Grit: The power of passion and perseverance. New York, NY: Scribner.

Park, B., Wilson, G., Berger, J., Christman, M., Reina, B., Bishop, F., Klam, W. and Doan, A., 2016. Is Internet pornography causing sexual dysfunctions? A review with clinical reports. Behavioral Sciences, 6(3), p.17.

Siems, W.G., van Kuijk, F.J., Maass, R. and Brenke, R., 1994. Uric acid and glutathione levels during short-term whole body cold exposure. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 16(3), pp.299-305.

Twenge, Jean M, Campbell, W Keith, and Gentile, Brittany, "Changes in pronoun use in American books and the rise of individualism, 1960-2008", Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 44, 3 (2013), pp. 406--415.

van Marken Lichtenbelt, W.D., Vanhommerig, J.W., Smulders, N.M., Drossaerts, J.M., Kemerink, G.J., Bouvy, N.D., Schrauwen, P. and Teule, G.J., 2009. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(15), pp.1500-1508.

Secondary literature and historical texts

Baden-Powell, R. 1908. Scouting for boys. Horace Cox.

Behlmer, G.K., 1998. Friends of the family: The English home and its guardians, 1850-1940. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Harris, B., 1997. Anti‐Alienism, health and social reform in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain. Patterns of Prejudice, 31(4), pp.3-34.

Hunt, A., 1998. The great masturbation panic and the discourses of moral regulation in nineteenth-and early twentieth-century Britain. Journal of the History of Sexuality, 8(4), pp.575-615.

Orwell, G. 1952. Such, such were the joys…. Partisan Review 19(5).