Research into genes and ethnic differences: should we?

On genetics, various kinds of racism, and institutional incentives

I wrote previously about genetics and ethnicity, arguing that in the genetics of ethnic groups, modern sample selection might be as important as ancestral natural selection. This article asks a more basic question: if we can do research into genetic differences between ethnic groups, then should we?

Trigger warning! This is a supremely sensitive subject for many deep reasons. Ethnicity is core to many people’s identity. History has made research into genetic differences taboo. Contemporary politics keep it controversial. Also, on a more trivial level, I don’t want this to become The Genes and Race Newsletter. I’m a social scientist, and genetics is just one of many interesting lines of research. Writing this piece makes me nervous. But it needs writing, as you will see.

Sneak preview: we will end up with a strong “yes”. A scientist’s first instinct should always be to find out; people without that motivation are in the wrong field. But curiosity alone is not enough of an answer. Not all discoveries make the world a better place — think of research into biological weapons. Maybe genetics is the same? Some people certainly think so.

Start with a helpful binary. Suppose that we can do this research: crunch some numbers and get an estimate of the contribution of genetics to intergroup differences in some socially important outcome, like earnings or education. That estimate will either be “none or trivial”, or it will be non-trivial.

If you believe the answer will be “none or trivial”, then it’s obvious, no? You should do the research. It will convert your surmise into a certainty. It will remove an argument made by racists, and more importantly, it will invigorate and focus the search for environmental causes of any difference. If you reckon true genetic differences on any outcome are small, you should be gung-ho to find out!

(It is tempting to add that researchers who are not gung-ho are revealing what they actually expect. Tempting but unfair: they may just believe that this research is hard to do and it’s easy to get mistaken answers. For today, I am simply assuming that problem away.)

What if the answer will be “non-trivial”? I think still yes, do the research. Here’s why.

White person medicine

What is institutional racism? Is it pervasive, or is it exaggerated by ideologues? These are deep questions, too deep to answer here, but if there is a clear example of institutional racism, meaning something like “institutions create worse outcomes for ethnic minorities, despite noone having any bad intentions”, then surely contemporary genetics provides it.

Modern genetic research requires data: big, expensive data, sampling hundreds of thousands of people. Not surprisingly it is mostly funded by rich countries, who, also unsurprisingly, focus on the outcomes that matter to their populations — overwhelmingly, health outcomes. Many rich countries are majority-white. So then, all our big expensive samples are majority-white.

This is a problem, because genetic effects differ across ancestry groups and ethnic groups. Perhaps this is due to “gene-gene” interactions, where genetic variant X affects you differently because your other genes are different; perhaps it’s gene-environment interactions, where X affects you differently because you’re in a different environment. Whatever the reason, if everyone in their samples is white and all their estimates are made based on white people, geneticists effectively end up doing “white person medicine”, which is correspondingly less useful to everyone else on the planet. That’s the institutional racism, and hence today there are big efforts to recruit diverse samples, which indeed are starting to pay off.

In short, the scientific community needs to do genetic research that explains variation on outcomes within different ethnic groups. Bottom line: we can’t do this research without also throwing light on intergroup differences. Within-group differences illuminate between-group differences! If you discover that (say) Ashkenazi Jews with two copies of the HBB gene get sickle cell disease, and those without it don’t, you have a potential explanation of why this group suffers more from sickle cell disease than the rest of the population. The same logic applies straightforwardly to traits that are affected by many genes. If you learn what makes some members of an ethnic group taller, you may be able to explain why some ethnic groups are taller than others. You’re not guaranteed to succeed — it’s well known that between-group differences may not have the same causes as within-group differences — but nor are you guaranteed to fail, and you certainly have a tool in your hand.

OK, but could we do this research just on health outcomes, without needing to explore behavioural or social outcomes?

Firstly, no, that is a fantasy. There is no hard and fast distinction between health and physical outcomes, and social and behavioural outcomes. Think of height again. That’s a straightforward physical measurement, right? Ha ha, no. As any man knows — I am 5’ 9’’ — height is fundamental to how people react to you, and so perhaps to how you perceive yourself. The same logic holds everywhere. Alcoholism is a disease: problem drinking is a behaviour. Depression; stress; mental illness; personality; resilience… there is no possible answer to where health outcomes end and behavioural outcomes begin.

Secondly, and for very similar reasons, we ought to do such research on behavioural outcomes. We have a moral responsibility to do so.

Heads below the parapet

Imagine a world where we didn’t know the cause of sickle cell disease. We persist in searching for environmental causes. People looking for genetic causes are denounced as antisemitic. Meanwhile, treatments are based on misunderstandings, genetic counselling isn’t given to Ashkenazi couples thinking of having children, and more people suffer needlessly. This would clearly be a terrible outcome.

Well, if there are non-trivial genetic causes of differences in social outcomes between groups, we are living in that world right now, and the exact same argument applies.

Take educational differences between black and white people in the US. (Sidenote: it is a sad fact about popular debate on genetics that “genetic differences” usually means IQ, ethnic groups means black and white people or occasionally Jews, and that in turn means those groups in the US. None of these reductions is accurate or helpful, and in some sense they are symptoms of US intellectual imperialism. But it’s where the debate is so I’ll go there.) These intergroup educational inequalities are real problems which require real solutions, not rhetorical ones. That means we need correct theories of their causes.

To think otherwise essentially involves claiming that for health research, we need to know the right answers, even if we find that genetics are involved in explaining intergroup differences, because that stuff really matters. But for behavioural outcomes, better leave that alone, because it could be controversial, and hey, who cares so long as we make the right noises?

I wish that argument were only hypothetical. Last month I was at the Behavior Genetics Association conference in Los Angeles. It’s a great community. I had a great time. I also got the strong sense that questions of race were hanging over the discipline like a shadow. Two keynote speakers, discussing the discipline’s history, mentioned the 1969 article “How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement” by Arthur Jensen, which raised a storm by suggesting that ethnic differences in education could be driven by genetics. One of them reiterated an earlier luminary’s advice to keep off the entire subject. The same topic came up in several hallway conversations. Efforts to diversify, of varying degrees of worthiness, were also going on.

I’d love to say this was all driven by a deep concern with ethnic inequity in the US and the world. I am afraid it seemed much more driven by a concern with the welfare of behaviour genetics as a discipline. One person in the hallway explicitly said he thought its survival was at risk: the Russell Sage Foundation had pulled a line of funding because of concerns about this area. Someone else said “I think the racists are leaving the discipline”. (Surely that can’t be bad? But in the context of US academia’s live-action replay of The Crucible, I get worried by smug remarks that villains are being driven out.) Another comment, about people who do research on race and genetics, was along the lines of “they are beyond the pale, but of course they’re useful in raising the issue”.

I don’t recall it sounding quite that cynical in context.

One cannot be too harsh. If behaviour genetics has a lot to offer the world, then its survival matters. Maybe if geneticists hadn’t made research on race a taboo, we wouldn’t have got the human genome by the 2000s? But at worst, this attitude substitutes virtuous pronouncements, and within-discipline affirmative action, for an actual concern with ordinary human beings: with people in southside Chicago, in Mississippi, or for that matter in Boston, Lincolnshire, who go through education systems and experience labour market outcomes — with the worlds of hope and struggle that lie behind those grey phrases. At worst, in fact, it is a piece of collective cowardice.

Falsehood bombs

This is not just a problem for an academic subdiscipline. Whole societies can be roiled by ethnic inequalities. Arguably, all multi-ethnic societies, so basically damn near all societies, carry on within a fragile interethnic equilibrium. I’ve described the UK Conservative government’s newfound interest in the problems of the white working class, and suggested why genetics might plausibly contribute to that group’s outcomes. If genetics do contribute to intergroup differences, and we go on assuming they don’t, then policies based on those false assumptions won’t fix the problem. We then set ourselves up for permanent ethnic conflict, with the whole panoply of special preferences for different groups. And to be clear, these preferences can very easily be applied to favour the ethnic majority, who, after all, have the votes. Just look at Malaysia.

Meanwhile, in the US, the University of California system plans to ban testing as racist. Plausibly, this will a) harm white kids; b) harm black kids; c) make the education system worse for everyone; and d) be hugely politically divisive, setting up more ethnic polarization in the US’s most populous state.

But what if?

A counter-argument is that if genetics do matter, this would be terrible news. Ethnic inequality would be baked in by nature. Racists everywhere would rejoice.

I don’t take this concern lightly, but I would make three points. First, it is easy to confuse “it being terrible for society” with it being terrible for me, my worldview, or (as with the BGA) my academic colleagues. Our societies have large and growing infrastructures of people devoted to diversity, equity and inclusion. I don’t accuse them of self-interest. It is easy even with good intentions — perhaps easier with good intentions — to believe that anything challenging your interpretation of racial inequality is illegitimate. It is easy to focus on a particular set of means, and to forget the ends they serve. (Think how often charities resist attempts to measure the effectiveness of what they do.)

Second, if genetic differences do contribute to outcomes, then understanding this will make environmental interventions more effective, not less:

We can estimate the effects of the environment better if we control for genetics. This is just Stats 101.

We can also find environmental interventions based on understanding genetics. If dark skin makes it harder for a person’s body to manufacture Vitamin D, then target milk advertising appropriately. That is the whole premise of genetic medicine. All the pathways of genetic effects go via the environment at some level.

This second point applies to social outcomes too. Here is an example, which does not require any sci-fi genetic intervention. Above, I mentioned height. Black children in school are sometimes said to be subject to adultification — being treated like an adult by authority figures, even when they are still kids. I’m no expert about this, but I see no reason to doubt it happens.

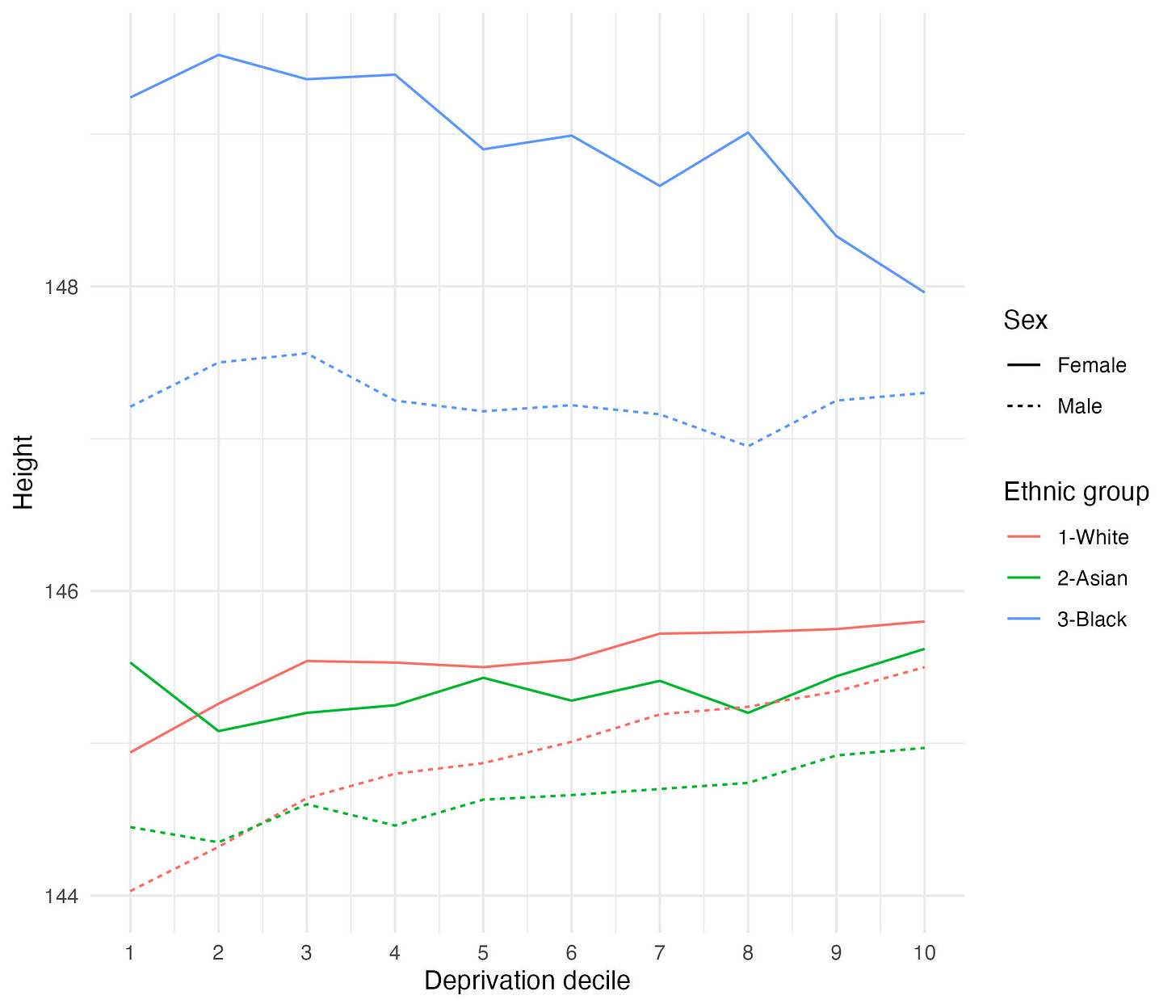

I would also guess that a teacher is more likely to treat someone as an adult if they look like one. Here are the heights for white, black and Asian year 6 kids in the UK (source):

(Girls are taller than boys at this age because of their earlier adolescent growth spurt.) Black kids of either sex are about 2-3 centimetres taller. It doesn’t seem likely that these differences are due to environmental disadvantages of white or Asian children, and indeed, differences across deprivation deciles are mostly not huge.

The correct response to this example is not “adultification? Ah well, black kids look taller so there’s nothing to be done!” Instead, it is to make educational staff aware that height differences vary between ethnic groups, and that they may not be good ways of judging a child’s maturity. You see? Thinking about biology, whether or not it’s genetic in this specific case, might help us target interventions better.

My last point is that non-genetic explanations of persistent inequality are not obviously either less politically toxic, or easier to address, than genetic ones.

Discrimination is not easy to fix, as George Orwell pointed out long ago, and as anyone who has taken the Implicit Association Test will be aware.

“Culture” as a group attribute seems to lend itself just as well to intergroup hatred as genetics. It is also in reality highly persistent and hard to change.

Dare to know

I don’t wish to be too sanguine about the effects of discovering that genetic differences matter. It would be political and social dynamite. But not discovering whether they do or not also has costs, which are less visible and more insidious. Ultimately, that strategy leads into a cul-de-sac where we commit to dishonesty as the price of our social theory.

Lastly, I haven’t said anything about what we would find if we do this research. I’ll repeat some points from an old blog post:

… if the natural differences hypothesis is true, it is true in a very different sense to that of the eugenics of the 20th century. In particular, “race” in the biological sense is not a box you can put someone in; it is shorthand for being a bit more genetically similar to some people than to others. Very few DNA variations are exclusive to any ethnic group. This means that statements about racial groups and (the genetics of) any characteristic are always probabilistic. They will be claims about averages. In particular, they should be interpreted, for any individual, in the light of other information.

We see important differences between ethnic groups on many outcomes — differences that affect people’s entire lives. Maybe genetics contribute to these differences. Or maybe they don’t. It is time to find out.

Throughout, I have been assuming that we can meaningfully answer whether group differences have genetic causes. More on that in future.

Genes are all very well, but culture goes deeper. My book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present is out. Get your hands on a copy from Amazon, or read more about it.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, please share it:

Subscribe to get this newsletter in your inbox:

Extremely belated but re-reading this after you linked it in your 'wrestling' post. Below 'Heads below the parapet', I think you meant Tay-sachs, which impacts ashkenazi jews, and not sickle cell, which impacts black people.

I am so grateful for professional researchers such as yourself and Razib sharing their findings to us lay-folk. I also value a forum such as this where I can engage/solicit your thoughts on this topic - so thanks!!

I'm fully aware that the following question holds potential for conflict, yet I'm attempting to find the reason why my logical inference would not follow from the following premises:

1) Reduced CAG repeats length in androgen receptor gene is associated with violent criminal behavior

2) Androgen receptor gene CAG repeat length varies in race-specific fashion in men (... without prostrate cancer)

Conclusion: there is a correlation between race and violent criminal behavior

Now I'm rushing to type this part. First, I have no idea how replicable these findings were (I've gathered they're more or less replicable, but dunno). Second, the correlation of these two findings do not imply a causal link. Third, if first two hold, the propensity of the combined effect is minor, or not distinguishable within the standard error. Fourth, if last three hold, the interaction between environment (nurture/culture) has a far larger effect on outcomes than the aforementioned genetic inclination. Fifth, and finally (!), this is an instance of a topic that we shouldn't investigate further due to... (pick your reason).

With these qualifications/rebuttals stated, how does one reconcile the fact base? I'm inclined, as you, to pursue these linkages simply due to the pursuit of knowledge. Furthermore, if the conclusion holds, I sure as hell want to know how significant it is, and I want to know how cultural intervention attenuates the undesired behavior in order to prioritize resources and develop appropriate/sensitive messaging. But all this is predicated upon my logical inference from 1) and 2), which may be faulty or statistically insignificant. Hence, my outreach.

Your input would be helpful on this topic. It's such a sensitive topic that it simply clatters around in my head out of sensitivity for others, and/or the entire point I'm exploring (the validity of the inference - not policy).

Thanks