On Nazis who read genetics

After the awful killings in Buffalo, I saw a thread on Twitter about how far-right groups keep up with work in human genetics. You can read the whole thing, but here are some highlights:

It is uncomfortable to think that your work might be on a Nazi reading list. What should geneticists do about this?

I’m not a geneticist, but I cosplay as one coauthor with one and know a little about the field, and maybe an outsider’s perspective can be interesting.

Genetics has always been fraught. Academics mostly like attention, but only my genetic research gets comments à la “DESTROYS Lefties with FACTS and LOGIC”, or alternatively “LITERALLY FASCISM”. The field has developed mechanisms to cope with this kind of attention, and some of them are quite good. For example, major papers often come out alongside a FAQ for the general reader.

At the same time, it sometimes feels as if the field is in a defensive crouch.

Here is an example. Genome Wide Association Studies use people’s DNA to predict things about them. As one of their byproducts, they create summary statistics – basically a big .csv file which says “this SNP had an effect of 0.003 on the dependent variable, this one had an effect of -0.002,…” and so on for thousands of SNPs. Researchers can use these summary statistics with other people’s DNA, to predict things about them. Normally, people share these things reasonably freely, because science.

The summary statistics for the latest GWAS on educational attainment had a set of conditions that were spotted by Emil Kirkegaard. (This is from the Google cache, since his website is currently down.)

So it’s time to download the new GWAS results and have another round of results, right? Well, no! There’s now a login page, and you need an institutional email too! There’s even an agreement you have to swear to:

I agree to conduct research that strictly adheres to the principles articulated by the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) position statement: “ASHG Denounces Attempts to Link Genetics and Racial Supremacy.”(See also International Genetic Epidemiological Society Statement on Racism and Genetic Epidemiology.) In particular, I will not use these data to make comparisons across ancestral groups.

Now, I hold no brief for Emil Kirkegaard, a man whose first reaction to the war in the Ukraine was “uh-oh, those refugees’ IQs won’t be very high”. But he is right that this is “the opposite of what open science stands for”. Frankly, it’s shameful. It’s also foolish. [NB: but see my June 28 update below.]

Scientists use data all the time. We often disagree about how to use data, and we criticize each other for it. Some people, approaches and subfields regularly do stupid stuff with data; as a result they are not taken seriously by the rest of the community. What we do not do is ban other people from using our data because we think they might use it wrong. (Imagine that in my field! If economists withheld economic data because someone might misinterpret it, we wouldn’t release any data, ever.) This is less like science and more like the idea attributed to Stalin. “Everyone knows that ideas are more important than tanks. We wouldn’t let our opponents have tanks, so why would we let them have ideas?”

Tactics like this create the impression that we are not being honest.

In the worst extreme, it leads to a kind of Intellectual Dark Web of counterknowledge, of The Things They Won’t Tell You. This kind of counterknowledge attracts smart people who think of themselves as independent minds, but it is also a honeypot for people who lack the critical resources to truly engage with scientific arguments. And some of its places can be very dark indeed.

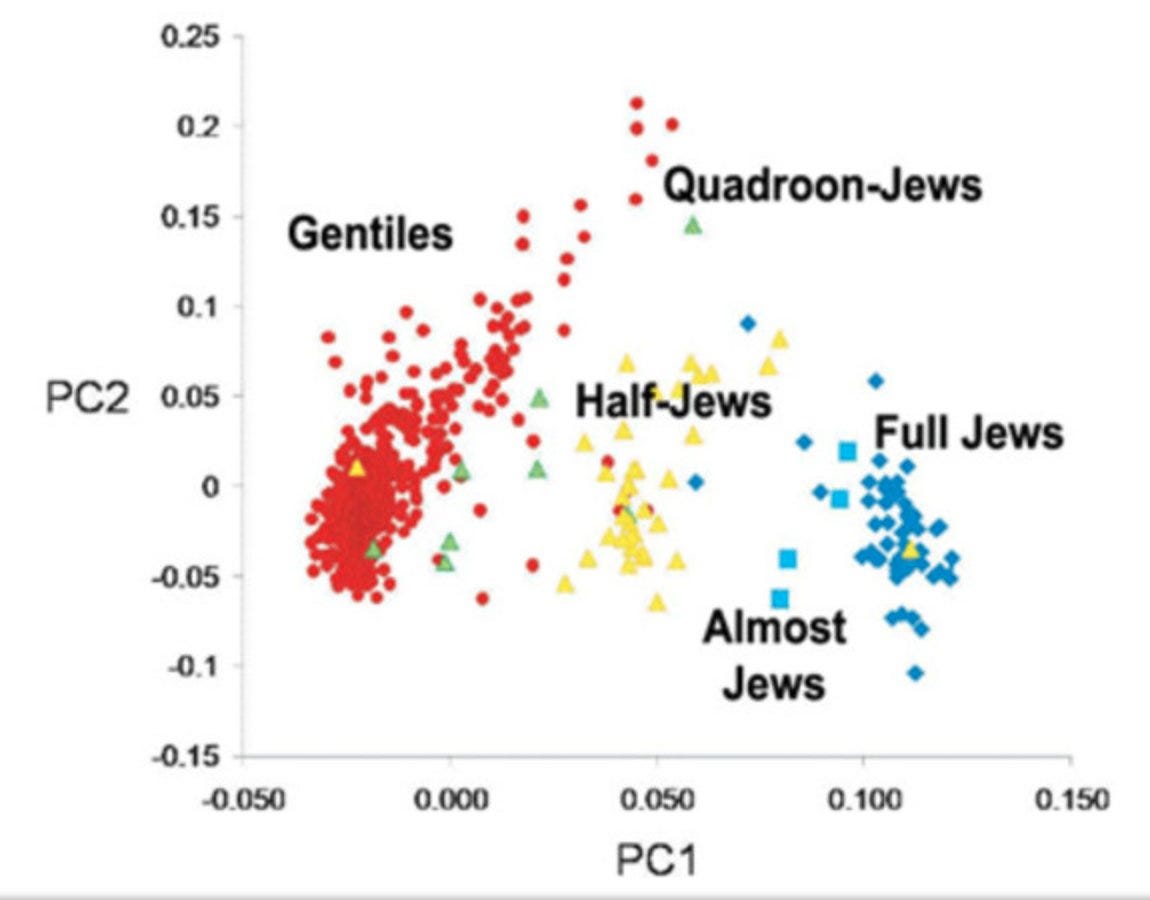

Imagine someone on the fringe of a far right group. I don’t mean a convinced and committed violent fascist — those people are probably beyond reach. I mean somebody who is tempted by those ideas. A dabbler. You get on one of these websites. You see pictures of the principal components of genetic analyses, which you probably don’t know how to interpret with complete accuracy:

… and then you hear that the people who did the latest genetics of education are hiding their data.

What are you going to think?

Here is another example. An argument on the twitter thread above was that “geneticists know” you can’t compare genetics across populations.

This gets asserted quite a lot. It’s a nice put-down to anyone who asserts that group X are different on measure Y because they are genetically different. Geneticists know you can’t make that comparison! However, I don’t think this is strictly true.

It is, for sure, true that genetic comparison across populations is hard. For example, most polygenic scores are created using samples of white people. As a result, they are less predictive when they’re used with other populations. If you draw the line linking the polygenic score for foo with actual foo, on non-white populations it will be a lot flatter. And you must be careful claiming that polygenic scores cause anything, because they often correlate with environmental factors — like, if you have a high polygenic score for educational attainment, your parents did too, so maybe you were raised in a rich and educated household.

But these difficulties do not add up to an impossibility. There are famous examples of genetic differences across populations. Why is sickle cell disease more common among sub-Saharan Africans or Indians? There’s a genetic explanation: the mutation linked to sickle cell disease also protects against malaria, and it is more common in populations whose ancestors lived where there is malaria.

Most traits aren’t linked to a single gene in that way, but there’s no reason in principle that polygenic scores can’t be different across populations. And if you want to understand how much that contributes to a group difference, you just capture the causal effect of your polygenic score on the trait in group A – maybe by running a within-family regression – and counterfactually ask, what if group B had the same distribution of scores as group A? Interestingly, you might then get a different result if you performed the same exercise on group B. But that’s OK. Science is complex! I think we knew that.

And indeed, people do this. For instance, there is a lively literature on how exactly genes contribute to height differences between people from different places. There are plenty of complexities here, but — and real geneticists are welcome to correct me here — I don’t think anyone in this literature is saying “impossible! It can never be done!” Presumably, if we learn that population differences in height are partly genetic, the liberal order will not collapse like a house of cards.

I suspect that when geneticists say comparing ancestral groups is impossible, what they mean is that it is scientifically difficult, and politically impossible. (Who’s going to fund you? Of course, for height you may get away with it.) There are, indeed, lots of important arguments about the ethics of such research. My point is simply: claiming it can’t be done is disingenuous. When we subordinate science to politics, we undermine our credibility as searchers after truth; we sow mistrust and paranoia; and ultimately, we strengthen, not weaken, the kind of people who hang out on channels like Iron Mirror.

For these reasons, I think recommendations like this need to be parsed very carefully:

Should we think about what we are doing? Of course. But I believe the approach of censoring research — I don’t say Jedidiah Carlson advocates that, but some people do — firstly, fails, and worse than fails, at its supposed object; and secondly, it succeeds at a much less avowable object. It will make far-right arguments more plausible, not less. But it will also play into the hands of authoritarians, who wish to centralize and politicize science. And we know that terrorist attacks can be instrumentalized by authoritarians in this way.

Science is positive-sum for humanity. But it is very much zero-sum in the short run. If you get the grant, I don’t. If I get the professorship, you don’t. Any ideology, no matter how noble, has a coalition of interests behind it. The risk is always that people import the “norms of politics”, as Paul Romer put it, into the field of science. Our theory is true, and we are fighting for the truth! But our theory will also get me a job.

There are large parts of academia where (a) the norms of politics are utterly dominant, partly because no questions are ever seriously resolved by the data; and (b) the use of politics in the wider sense — of a competition to show that the other person’s work, maybe just the language he uses, has hidden racist, sexist or colonialist assumptions — is an accepted and widely used fighting technique. These people, I fear, do not fight clean; and because they don’t do actual science, they have a lot of time to practice their mobbing skills. We do not want this approach to spread into real science.

In this context, the ability to pull the plug on someone’s research, not because it’s wrong, but because it’s dangerous and fascist, is like a shotgun on the wall in a Western saloon. You know it’s going to get used some time, and not necessarily by the good guys.

And tweets like this suggest we have real trouble:

This seems close to an argument that “nothing works”. Your FAQs aren’t gonna help, because 18-year-old Nazi murderers are not actually perusing the literature very hard! (Who knew?) What do we do? Do we just stop publishing graphs, and write scientific prose so convoluted that nobody can understand it?

(I should add that Jedidiah Carlson is, very wisely and thoughtfully, unwilling to leap to policy suggestions, and the one he does make is simple but judicious:

But I don’t think everyone else will be so calm.)

You may think this issue is a trivial scientific bunfight, compared to the really dead people in Buffalo. I do not think it is as simple as that. The trust that science should receive, and that it must continually be earning, is a political issue. Loss of trust in institutions feeds political extremism. We have seen the interplay between these issues in, for example, COVID denialism and the German Querdenker movement.

A last comment. I do not think of myself as a scaredy-cat. I like political fights. I’m not a geneticist: if a bigwig in that field decides I must never get another grant, I will survive. Yet, I hesitated before publishing this. I have a paper under review right now. Could I jeopardize its chances? Shouldn’t I hang fire… just for a week? I went ahead only because the issue is urgent. Cowardice is bad, academic time-serving is bad. The incentives towards them are strong. We need to be mindful of the environment we create, by our silence as well as our actions.

Update 28 June 2022

I spoke to an author of the EA4 study at the recent BGA conference and he commented that the requirements for accessing summary statistics were relatively weak — you just had to acknowledge that you’d read and understood the ASHG statements on genetic diversity and racial supremacy. I recently logged in to the SSGAC and this is indeed true. In particular, the language I quoted above is not now present: you don’t have to commit to do or not do such-and-such research, and you don’t have to agree with the ASHG statements, just understand them. So, if this is the current version for EA4 as well, I’d take back my comment that this is shameful. I think the current language is a reasonable approach.

Here are more thoughts on the practice of science. Here’s why to be suspicious of counter-intuitive results. If you liked this post, why not subscribe?

Also, why not share it on social media?

Lastly, check out wyclifsdust.com, the website for the book I am writing. You can get a free chapter.