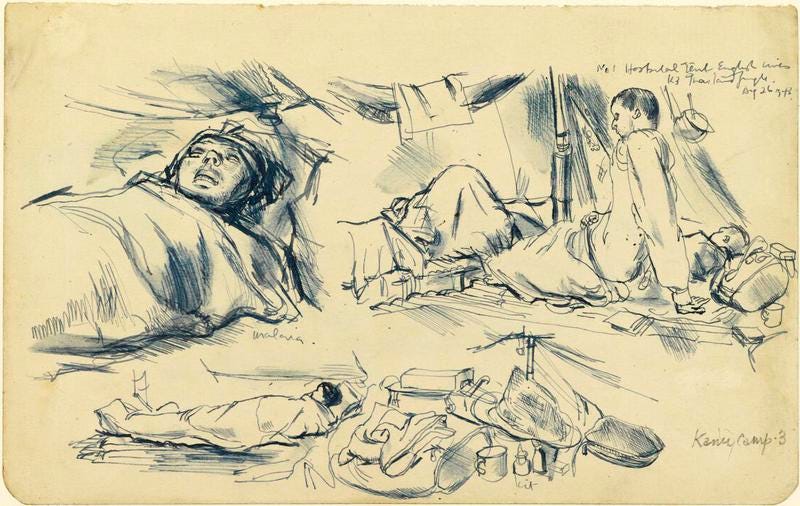

Malaria

Once upon a time, the inhabitants of the island began to suffer from malaria.

Nobody knew exactly what malaria was caused by. Was it the newly introduced habit of wearing tricorn hats? The craze for bagpipes? Or was it the recent fashion for swamp parties? Whatever it was, the death rate kept going up.

People didn’t like malaria. They wanted healthy, malaria-free lives. Thinking that they might get malaria was uncomfortable, so they preferred to avoid the topic. Looking forward, they tended to assume that they wouldn’t be the ones to get malaria, even though the death rates tables were publicly posted on the hospital walls. People who did get malaria tried to stay positive. They would say “you can live well with malaria” or “malaria has made me a stronger person”.

In addition, because malaria affected the young especially, pretty soon there weren’t enough people on the island to take care of the old. And death rates were high enough that in future, the population was projected to decline even more.

The king and his advisers didn’t have a health department. They’d never really had to think about malaria. They were more focused on building large construction projects. In previous centuries, the islanders had suffered from living in poky straw-roofed huts. Monarchs had always won acclaim for building tall concrete buildings for people to live in. Even though now there were enough buildings for everyone to have a comfortable flat, two comfortable flats, or even three, the king still thought that large construction projects were the way to prove he was a good king. “But,” said some people, “if we all die of malaria, soon these buildings will stand empty!” Others even thought that the construction projects, some of which were built on marshy ground, might have something to do with the malaria.

“Never mind,” replied the king’s advisers on the Large Construction Council. “The main thing is to build taller buildings. We can always get other people from other islands to live in them.”

The king brought in people from other islands. They didn’t suffer from malaria. They didn’t hold parties in swamps or wear tricorn hats. They worked hard, too, because they weren’t secretly afraid of getting malaria. Many of the native inhabitants got angry, because the new workers wouldn’t share in their customs and traditions. However, some of the new workers did begin to wear tricorn hats and join swamp parties. These hat-wearing new workers were popular, but pretty soon, they started to get malaria too. As a result, not many of the other new arrivals joined them. “We can all get along,” said the Construction Council, “so long as all new arrivals wear tricorn hats on Tuesdays, and attend at least one swamp party a month.”

For the first time in the island's history, a political party was formed. “Get rid of the foreign workers!” was their slogan. “They are the cause of all our problems! They don't play the bagpipes, and they keep away from swamp parties!” Some even whispered that the foreigners had spread the disease by selling malaria-infected toothpaste.

At last some members of the Construction Council started to look into the cause and treatment of malaria. This was controversial. People didn't like thinking about malaria, since it threatened the very existence of the island. Malaria research was associated with conspiracy theorists and “tootherism”. Eventually, a report came out. It proposed that workers who didn’t get malaria should be rewarded with a gold plaque. One radical even suggested giving them a new, extra-large flat. But the Construction Council had to bear costs in mind. They compromised: malaria-free workers would get a cuckoo clock. “The main thing,” said the Council, “is that this year, we built a record number of tower blocks.”

At the back of the meeting, someone spoke up: “I’m not sure about building on all these marshes.” “Do you want us all to live in mud huts?” the head of the Council replied.

This is a parable. The island is the developed world. Malaria is the secular decline in birth rates to below replacement level. Like the island's inhabitants, we do not really understand our problems. We know birth rates have declined, and we assume it is something to do with the ways our societies have changed in the past 50 years.

Just as malaria is bad for the islanders, declining birth rates are bad for us. Most people want to have a family. Many of them fail to do so. They often adjust their expectations down. Of course, it's possible to be happy and childless, and many people actively choose to be childless. But common sense tells us that it is natural to want to raise children.

The king and his Construction Council are like policymakers who focus on economic growth. Most people think about earning money as part of a life plan that involves starting a family. But policy in developed countries treats GDP growth as an end in itself, like the Council's tall buildings. In fact, just as building in swampland might increase the risk of malaria, some parts of the modern economy may harm families and reduce fertility.

Low birth rates increase the dependency ratio, meaning that fewer workers have to support more pensioners. Like the king, policymakers and researchers think they can solve this problem with immigration.

The workers who don’t play bagpipes or go to swamp parties are like immigrants who hold on to their traditional cultures, and who retain high birth rates. Playing the bagpipes is awesome, but going to swamp parties might not be so good. Similarly, Western culture is not sustaining an above-replacement birth rate, so adopting it wholesale is not attractive. The workers who decide to go to swamp parties are like immigrants who adopt the host culture. As a result, their birth rate declines.

The anti-immigrant party, of course, represents modern populists who blame immigration for their own society’s problems, and who demand that immigrants adopt Western culture. Tootherism is like the “great replacement” conspiracy theory, which blames low fertility on a Jewish plot. The Council’s response is like the politicians who respond to the populists by talking vacuously about integration.

The Council report, with the offer of a gold plaque, is like policy proposals to improve the birth rate by offering people money to have babies. These don’t work for two reasons. First, they’re too small to matter, like the gold plaque or the cuckoo clock. Second, even if they were bigger, like the offer of an extra flat, they misunderstand the problem. The islanders don’t get malaria because they want to get malaria. They would like to avoid malaria, but their social institutions (swamp parties) don’t let them. Similarly, people aren’t, in general, childless because they don’t want children under any circumstances. They are childless because they are in a society which makes having children difficult.

A glance at the happiness data might help us understand that. The conventional wisdom is that children are a joy. A long-standing puzzle in happiness research is that in the data they seem to be the opposite. People without children are happier than people with children. So, am I wrong, along with all previous generations, and really “malaria is good”? No. (Side note: in social science, show me a counter-intuitive result, and I’ll show you a result ripe for debunking.) If you split the data into single parents versus couples, couples with children are happier; singles with children are not. The counter-intuitive result comes from our society having many single people raising children. This makes much more sense. Many things become much harder for single parents — like leaving the house when your child is home without making arrangements in advance. Well, if you have a child with someone now, the chance that you will end up raising the child on your own are quite high and not inside your control. That may not be a bet you want to take. If so, that does not imply that you “don’t want children”. Your choice is being made under constraints.

The solution for the islanders is obvious, to an outsider. They should learn what causes malaria, and stop going to swamp parties. Maybe the government should ban swamp parties, or maybe they will go out of fashion once the truth is known. The important thing is that they stop.

The solution for us is the same. We should figure out which of our social institutions are preventing people from having children, and change those social institutions. It doesn't matter whether this happens through government policy or otherwise. Many minority cultures do not have below-replacement birth rates, even though they share the same laws as the rest of us, so government action does not seem to be necessary.

The most important first step for the islanders is to say “we have a problem with malaria. Malaria is bad. Building more tall buildings will not help.” I won’t belabour the point.

The post was partly inspired by this well-known fable.

If you liked this content, then I would love you to do three things:

Subscribe to this newsletter. It’s free, posts are occasional, and subscribers make me happy.

Share this post on social media. This is a new venture, so referrals are a big deal for me.

Read about the book I’m writing. It’s called Wyclif’s Dust, too. You can download a sample chapter. You might like it.

Complicated metaphor. *Getting* malaria is like *not* making babies?