A pattern in world history

Do societies and nations contain the seeds of their own decay?

Here is something that happens a lot. A group of people share a resource in common. The group starts off small. But gradually it grows. Then this process picks up speed. As more and more people are allowed into the group, the value of membership goes down. Eventually, the group becomes a club that is not worth joining. Then another, smaller group, perhaps from within the original membership, takes over and gets access to the resource, and the cycle starts again.

This is a notorious pattern where the resource is political power. Royal councils expand, lose the ear of the king and become purely honorific bodies. Meanwhile real power has shifted to those with better physical access, perhaps personal servants.

The Roman Senate started with 100 members under the early kings, and expanded to 300 in 509 BC at the inauguration of the Republic. By Caesar’s time there were 900 senators; Augustine reduced them to 600. They were practically politically impotent under the Empire, and completely so by Diocletian, when power had shifted to the imperial bureaucracy. But their numbers kept growing — 2000 in the 4th century. Constantius II, the second Byzantine emperor, created a Byzantine senate with 2000 members, but it was already more of a “city council” than a true governing body. Meanwhile in Rome, by 593 AD, Pope Gregory I could complain that “senatus deest” — the Senate is AWOL. Presumably there were no longer even any benefits worth turning up for.

The House of Commons had 300 members in the 16th century, 500 by 1688, and 658 by 1800. Around the turn of the century there were 60 ministers in the British government, and 19 members of the Cabinet. By 1950 there were 81 ministers, by 2000 106 and under Boris Johnson 134 ministers. At this point the growth was partly due to the “payroll vote” — in other words, the benefit of being the marginal minister was the salary, not actual political power. “Kitchen cabinets” or “sofa government” took the real decisions.

On the small scale, organizations often have large bodies with nominal power and small executive bodies with real power. Think of university senates, for example.

Plausibly there’s a simple logic behind this pattern. Letting new people in dilutes the resource: when a committee expands, each individual member has less sway. So keeping potential entrants out is a public good shared among the committee. In a small committee, each member has a strong incentive to carefully vet any new entrants. Once the committee has already grown large, the public goods problem bites hard: no individual member has much incentive to stop new people joining.

At the same time, a bigger membership makes a committee less politically effective. As any manager knows, a group beyond a certain size cannot be a decision-making body. A larger body may be able to exercise veto rights or perform scrutiny, but this too becomes less effective beyond a certain point. So, as a committee expands, it creates a demand for a new body to actually get things done; the original committee’s emphasis shifts from political power to material benefits or symbolic status.

Perhaps this pattern fits not just committees and legislative bodies, but entire nations and societies.

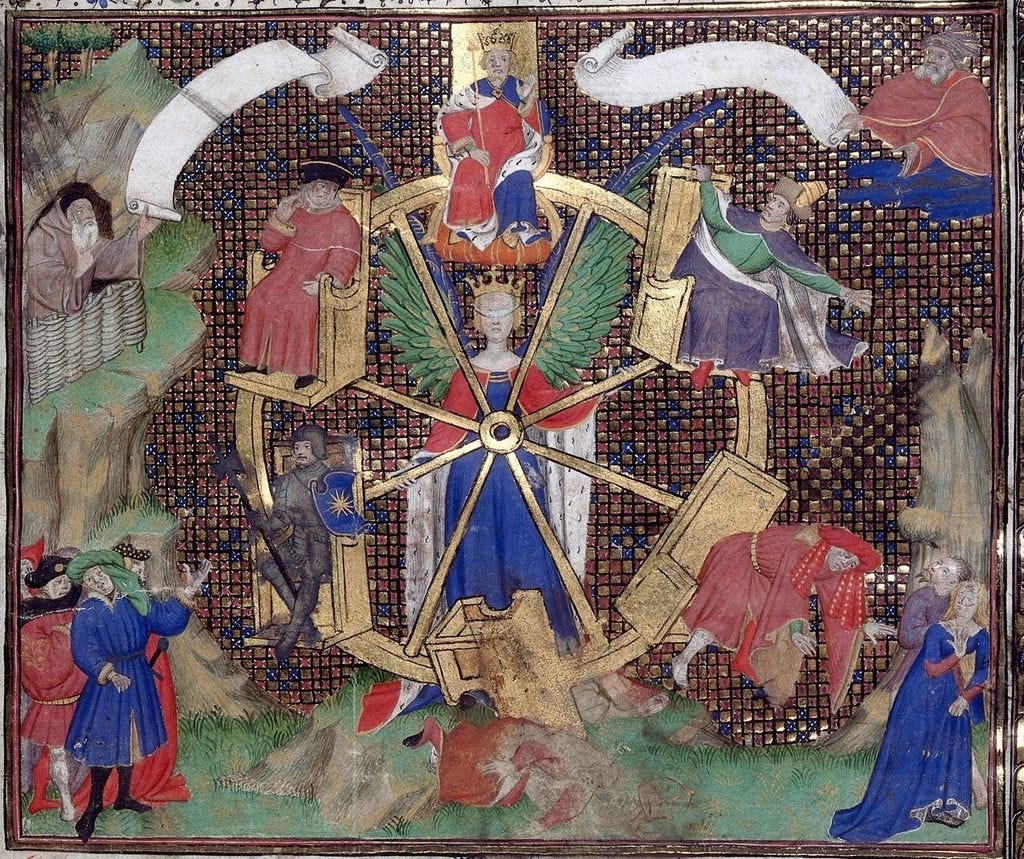

The first person to suggest it was Plato. Book 9 of the Republic describes the shift of political forms from oligarchy to democracy and thence to tyranny. (Actually, he starts off with a kind of militaristic society which he calls a “timarchy”, or rule by honour.) His explanation of how this happens involves factors that are quite specific to Greek society. When the poor notice that their oligarchic rulers have got lazy and rich, they take over by violence. In turn, democracy is subverted by class war: a populist tyrant arises to defend the poor from the rich and redistribute land. It’s fun to draw modern analogies to Plato’s description of democracy:

if any one says to [the democratic man] that some pleasures are the satisfactions of good and noble desires, and others of evil desires, and that he ought to use and honour some and chastise and master the others — whenever this is repeated to him he shakes his head and says that they are all alike, and that one is as good as another….

In such a state of society the master fears and flatters his scholars, and the scholars despise their masters and tutors; young and old are all alike; and the young man is on a level with the old, and is ready to compete with him in word or deed; and old men condescend to the young and are full of pleasantry and gaiety; they are loth to be thought morose and authoritative, and therefore they adopt the manners of the young.

And oh horrors!

The last extreme of popular liberty is when the slave bought with money, whether male or female, is just as free as his or her purchaser; nor must I forget to tell of the liberty and equality of the two sexes in relation to each other.

But don’t get lost in the detail — the key point of Plato’s dynamic is just that decision-making expands until the bubble pops. The cycle goes from rule by a few to rule by many, and then back to rule by one; not the other way round.

From this perspective, the past five hundred years form a single cycle. We start with the early modern emergence of Renaissance kingship, and the development of “divine right” ideology to justify it, out of a more fluid and polycentric medieval world. From the seventeenth century, parliaments challenge the single royal executive, and royal rule is replaced by republics, sometimes violently. Over the 19th century the franchise is expanded; gradually democracy comes to seem like the inevitable endpoint.

Then what? In the 1920s, you might have said “now, sclerotic democracy will be replaced by a more efficient government — a single Duce!” Well, things did not turn out like that. But the logic above is an internal one: it doesn’t say anything about which state form will win in an external contest like World War II. So we might wonder whether democratic institutions now are vulnerable to the development of “effective” non-democratic alternatives. (By the way, did you know that the UK government had tasked the Bank of England with decarbonizing the economy? I did not!)

I think this pattern also provides an alternative explanation for a puzzle I mentioned before:

Why don’t we see more large oligarchies, i.e. countries with a mass but not universal franchise? The answer here is that the committee/electorate grows faster as it gets larger, because the members face a collective action problem in preventing expansion.

Painting on an even bigger canvas, and perhaps stretching the model to its limit, you might even see this pattern in the development of Christianity. One interpretation of the Reformation is that the Catholic church was an institution that provided certain public goods to its members. (This is the interpretation of Rodney Stark’s Rise of Christianity and I think also of John Bossy’s Christianity in the West 1400-1700.) And by the late medieval period, it had expanded its membership as far as it possibly could, and at the same time its institutions for mutual benefit were no longer entirely doing their job. The early Reformers provided new, modernized forms of public good provision — literacy, for instance — but amongst a narrower and more exclusive group.

What I like about this pattern is that it seems to provide a general explanation for cycles of political reform and decay. I think we are a bit short of such general explanations, which is surprising because surely political decay is a very widespread phenomenon. But a lot of political economy is more focused on explaining how political systems function than explaining how they change. And current historical work seems to be very sceptical of “internal decay” explanations for anything. (For instance, modern historians say the Western Roman Empire fell not because of “bread and circuses”, but because of contingent events like climate change and the Vandal invasion of West Africa.) I suspect they might be missing a trick.

If you enjoyed this, you might like my book Wyclif’s Dust: Western Cultures from the Printing Press to the Present. It’s available from Amazon, and you can read more about it here.

You can also subscribe to this newsletter (it’s free):

Interesting view. Lately, I have been having similar thoughts but from the angle of how technology affects societies. Technologies which we develop to make our lives easier, inevitably contain the seeds of our own destruction.